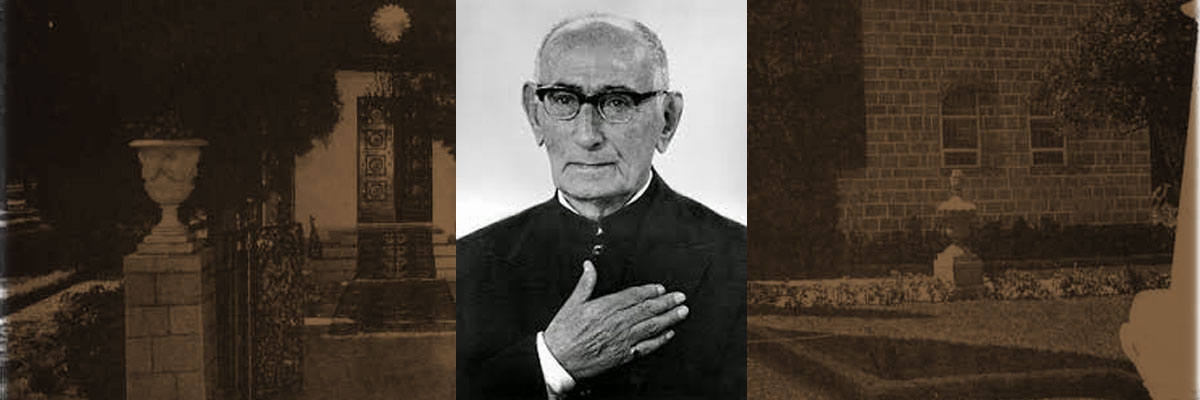

Clara Dunn

Clara Dunn

Born: May 12, 1869

Death: November 18, 1960

Place of Birth: London, England

Location of Death: Sydney, Australia

Burial Location: Woronora Cemetery and Creamatorium, Sutherland, Australia

John Henry Hyde Dunn

Born: March 5, 1855

Death: February 17, 1941

Place of Birth: London, England

Location of Death: Sydney, Australia

Burial Location: Woronora Cemetery and Creamatorium, Sutherland, Australia

The couple who went to Australia in 1920 in response to ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s call for worldwide expansion of the Bahá’í Faith and firmly established it in the antipodes; both designated Hands of the Cause of God by Shoghi Effendi—Clara among the second contingent in February 1952, and Hyde in a posthumous appointment announced in April 1952.

John Henry Hyde Dunn, the youngest of twelve children, was born in London. Details of his early life, including the date of his birth, are scarce or unreliable. Several different dates for his birth are recorded; the one used on his tombstone is March 5, 1855.

In his later years, Hyde, as he was known throughout his adult life, preferred not to talk about his childhood, which seems to have been difficult. His mother died when he was young. When his father, a consulting pharmacist, remarried, strains between Hyde and his stepmother evidently led to a loosening of Hyde’s family ties.

As a young man, Hyde worked for a London firm as a sales agent in England and France. Later, after emigrating to the United States (possibly by way of Canada), he was employed as a traveling sales representative for the Borden milk company. He lived on the West Coast with his first wife, Fannie, and had a stepdaughter, Hattie Oliver Periard.

In a tinker’s shop in Seattle in 1905, Hyde overheard Nathan Ward Fitz-Gerald, a spirited and colorful Bahá’í teacher, quoting the words of Bahá’u’lláh: “Let not a man glory in this, that he loves his country; let him rather glory in this, that he loves his kind.” Attracted by these words, Hyde soon became a Bahá’í. In the process, he later told friends, he gave up smoking and drinking and experienced a personal transformation. Such outstanding early American Bahá’ís as Thornton Chase, Lua Getsinger, and Ella Cooper assisted Hyde in his close study of the Bahá’í teachings.

Hyde’s searching and earnest letters to Thornton Chase, inquiring into the deeper teachings of the Faith, prompted his mentor to write several pages addressing such themes as the nature of fear, the station of the Persian Bábí and Bahá’í martyrs in comparison with the American Bahá’ís, the resurrection of Christian teachings through the Bahá’í revelation, and the mistaking of the holy spirit for the spirit of man. “Your letters are such a pleasure to me,” Chase wrote. “I see shining through them the earnest soul, which has tasted of heavenly food and found it so delicious that it ever hungers for the Table of the Lord.”

Hyde taught the Bahá’í Faith enthusiastically in California, Oregon, and Washington and was among the first to teach it in Nevada. For a time, he traveled with Fitz-Gerald to share the new religion with others. In 1905 Hyde met Clara Davis when he entered the medical office where she worked in Walla Walla, Washington, to post an advertisement for a Bahá’í meeting that he and Fitz-Gerald were holding that evening. Hyde asked Clara if she was interested in spiritual things. She replied that she would be if she knew of any. After Hyde told her a little about the Bahá’í teachings, she asked whether the new religion was “for everybody.” On being assured that it was for the whole world, she agreed to attend the meeting. After the meeting, perceiving that the two men had not eaten, she insisted on giving them supper. Over the meal, they told her more about the Bahá’í Faith. She began to investigate the new religion and, some time later, became a Bahá’í.

Clara was born in London, England, on May 12, 1869. She was the sixth of eight children of Thomas Holder and Maria McHugh, who married in 1857 in Dublin, Ireland, and later settled in London. Thomas Holder, who had served in the Crimean War, became a farmer, then joined the police. In 1870, when Clara was a year old, the Holder family left England for Ontario, Canada, where Thomas found employment in a railway workshop in Allandale, near Barrie.

Clara’s childhood was marred by poverty and domestic tension; her father, a Methodist, and her mother, an Irish Catholic, constantly argued over religion. At the age of sixteen, Clara left her unhappy home, marrying William Allen Davis in Toronto on December 24, 1885. Yet happiness eluded her. In close succession she gave birth to a son, Allen, in April 1887, and lost her husband through an accident at work. A widow and the mother of an infant while still a teenager, Clara sought to support herself and her child by training informally as a nurse. She found it difficult, however, both to raise her son and to earn a living, especially after she became ill with typhoid and was unable to work during a lengthy recovery period. Reluctantly, she put Allen into the care of her eldest brother, Henry—a decision that, over the years, was to cause her continued pain. In 1902 she moved by herself to the United States, settling in Walla Walla, a town in southeastern Washington state, where she obtained work in a medical office devoted to the Viavi treatment, a new and unorthodox approach to healing.

On accepting the Bahá’í teachings, Clara found herself part of a small group of Bahá’ís in Walla Walla. The community consisted of a “tiny band,” described in a contemporary account as “sickly” and “very feeble,” with some of its members inclined to commingle their inadequate knowledge of the Faith with other ideas. Far from other centers of Bahá’í activity, it lacked the strength to deal with demoralizing opposition from local religious leaders or to nurture Clara as a fledgling Bahá’í. Alone, unable to spark interest in the Bahá’í Faith among her friends, and sensitive to criticism from those who called her a quack because of her commitment to the Viavi treatment, Clara suffered a nervous breakdown. She could not work for some time and only gradually regained her health.

In October 1912, when ‘Abdu’l-Bahá visited the San Francisco Bay Area for eighteen days, Clara was so short of funds that she almost did not make the journey of some sixteen hundred kilometers (one thousand miles) to meet Him. At last, she managed to borrow money for a train ticket. Arriving in San Francisco on the final full day of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s visit, she found herself in a strange city with no clear idea of the address she sought. She followed the vague instructions she had been given and somehow managed to find the house where He was staying. The first person she saw there was Hyde, who had arranged to be in San Francisco for a week to hear as many of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s addresses as he could.

Although the time that Hyde and, especially, Clara spent in ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s presence was brief, He made an impact on both of them that lasted for the rest of their lives. Clara often recounted a story—told with much laughter by ‘Abdu’l-Bahá during dinner—about a woman who took her duck to market, claiming that it was the biggest duck. For Clara, the moral of the story was that she should control her ego and an inclination to exaggerate. The story, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s radiant smile, and the delicious taste of the rice they ate that night remained vivid memories that Clara continued to share with others for nearly fifty years.

After ‘Abdu’l-Bahá left San Francisco, both Clara Davis and Hyde Dunn carried out their activities as Bahá’ís with new dedication—Hyde living across the bay in Oakland and Clara in San Francisco. In March 1916 Hyde’s wife, Fannie, died, having accepted the Bahá’í Faith shortly before her death. Over the next year, the friendship between Clara and Hyde deepened, and they married in July 1917. They lived in Oakland, later moving to Santa Cruz, and often hosted Bahá’í meetings or spoke in the homes of others. The couple invariably rented a well-appointed apartment or cottage, rather than a simple one, to have pleasant surroundings in which to present the Bahá’í Faith. The remainder of Hyde’s income was spent almost entirely on their teaching activities—on travel, Bahá’í literature, and the food with which they served the many guests who attended meetings in their home.

In 1919, Clara and Hyde read ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s call, in a series of letters called the Tablets of the Divine Plan, for teachers to take the Bahá’í Faith to all the countries of the world, traveling as He longed to do, “even though on foot and in the utmost poverty,” to promote the Bahá’í teachings. Clara later recounted that she looked up from the page she was reading aloud to Hyde and said, “Let us go where ‘Abdu’l-Bahá wished to go,” adding “We are almost in poverty.” Hyde replied unhesitatingly, “Yes, we will go.” They decided to set out immediately for Australia, where no Bahá’ís resided.

After Clara suggested that Hyde might proceed alone to save the expense of her ticket, they cabled ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, asking whether both should go. He replied, “Highly commendable,” thus settling the matter. Some of the San Francisco Bahá’ís expressed concern that an “elderly couple”—Hyde in his sixties, Clara fifty—intended to travel so far to spread the Bahá’í message. Hyde is reported to have replied that he would sooner die than not respond to ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s call. In January 1920 a large group of Bahá’ís from the San Francisco Bay Area, as well as the Dunns’ good friends John and Louise Bosch from Geyserville, gathered at the dock to see the couple set sail.

Following a sojourn in Hawaii, Hyde and Clara traveled to Sydney, landing on 10 April 1920. They were accompanied by Clara’s son, Allen, who had joined them in Honolulu and remained with them for a time in Australia. “We arrived in Sydney . . . with naught but faith in ‘Abdu’l-Bahá,” Hyde recalled a decade later. Their lack of funds brought distress in the first few months. Both Hyde and Allen fell ill, and Clara, finding “very little strength left” in Hyde, hoped that she and Allen would be able to earn enough to allow Hyde to devote himself wholly to Bahá’í activities. Fortuitously, Clara found work at the Viavi office in Sydney.

Within the year, however, Hyde regained his health and obtained a position as a traveling representative for the Bacchus Marsh Milk Company (soon after acquired by Nestlé), enabling Clara to give up her job. Initially, he worked within New South Wales. After he outperformed all other company sales agents, the management gave him nationwide responsibilities. In the next decade his work took him to every state and major city and town in Australia.

Typically, when Clara joined Hyde in his travels, they would rent a cottage in the state capital. He would then travel to country towns during the week, while Clara remained in the city, making friends, involving herself in charitable activities, and inviting people to weekend meetings at which Hyde would speak. By July 1923 Hyde had visited 225 towns, an average of one new town for each four and a half days of work from the time he started at Nestlé.

In Australia postwar skepticism, in addition to growing disillusionment with the sectarianism and dogmatism of the major churches, contributed to increased interest in alternative religions and philosophies. Hyde continued to speak, as he had done in North America, to such religious groups.

Despite the Dunns’ efforts, progress in attracting new adherents was slow for the first few years. A turning point came toward the end of 1922. After Hyde and Clara had spent more than two years traveling and meeting scores of people, two Australians became Bahá’ís. First, Sydney optometrist Oswald Whitaker, who had been interested in Theosophy, accepted Hyde’s definition of “love” as being “THE whole law and power of the Great Universe.” Soon after, Effie Baker, a photographer and model maker, accepted the Bahá’í message immediately after hearing Hyde talk at Melbourne’s New Civilization Center.

At the end of 1922 Clara and Hyde, using a month of holiday time that he had accumulated over two years, traveled to Auckland, New Zealand. They were unaware initially that a lone New Zealander, Margaret Stevenson, had been a confirmed Bahá’í for some years—”holding the fort and waiting for reinforcements,” as Clara put it in a letter to a friend in California. Hyde’s first talk in Auckland, to about twenty people in a private home, was “lucid and satisfying” and made “a deep impression on most of those present,” according to an account provided some years later by the Auckland Bahá’ís. “Other meetings followed, some in private houses, several at the Higher Thought center, then newly established, at Spiritualist Churches, and other unorthodox communities.” These meetings, and other gatherings in the afternoons at which Clara discussed the Bahá’í teachings, led to the formation of a study group. Clara observed that in Auckland their efforts to teach the Bahá’í Faith achieved immediate success: “We seemed to have done more in two weeks here than we did in Australia in two years.” Although Hyde had to return to Australia, Clara stayed in Auckland until April 1923, nurturing the small band that became the nucleus of the Auckland Bahá’í community.

In Melbourne, where the Dunns were based for a time, Hyde found a new receptivity. On Friday evenings, he spoke in the home of an herbalist to audiences of over one hundred. Another visit to Melbourne led to invitations to speak at a Theosophical lodge, spiritualist churches, an occult church, and the Lyceum Club.

Clara and Hyde Dunn had complementary personal qualities that enabled them to become successful promoters of the Bahá’í Faith. Clara combined a charitable nature with a gentle but determined manner. She often used her nursing skills to care for others. She gathered people around her and was able to rally them quickly to a just cause. Through her own suffering, she had developed a sense of compassion for those close to her and for others whose plight she came to know. Friends have described her as warm, humble but self-assured, graceful, serene, and fun-loving.

Hyde had a friendly, outgoing disposition and a distinguished, upright appearance. He retained his English accent and spoke in an engaging and inspired manner, drawing people to him without ever seeming to be overbearing. Those who heard him speak were struck by “the unearthly light that suffused his whole personality” when he talked about the Bahá’í Faith.

Hyde had a friendly, outgoing disposition and a distinguished, upright appearance. He retained his English accent and spoke in an engaging and inspired manner, drawing people to him without ever seeming to be overbearing. Those who heard him speak were struck by “the unearthly light that suffused his whole personality” when he talked about the Bahá’í Faith.

With business acquaintances Hyde was a keen observer of economic and political conditions; nevertheless, he felt that, “for want of training and technique,” he lacked the ability to express himself fully, and he relied to some extent on the intellectual assistance of friends. In conversation and in correspondence with Bahá’ís, however, he was both confident and eloquent. He was especially enthusiastic in advocating the close study of scripture. Hyde once told Gretta Lamprill, the first Bahá’í of Tasmania, that Bahá’u’lláh’s Hidden Words had been to his “thirsty longing soul like a balm or pure water on the hot desert of search and longing.”

During the 1920s the Dunns patiently nurtured individuals and fostered the growth of small and isolated Bahá’í communities across Australia and New Zealand. Mother and Father Dunn, as the new adherents began calling them, guided the Bahá’ís toward establishing local governing councils, or Spiritual Assemblies, in preparation for eventually electing a National Spiritual Assembly. The first Local Spiritual Assembly was established in Melbourne in December 1923, followed by Perth in July 1924 and Adelaide in December 1924. These Assemblies lacked firm foundations and declined when the Dunns moved to another city; subsequent visits were required to revive them. Assemblies established in Sydney in April 1925 and in Auckland in April 1926 proved to be stronger.

Distinguished Bahá’í travelers from North America assisted the Dunns with the process of gaining media attention and expanding the Bahá’í communities of Australia and New Zealand in their formative years: Martha Root in 1924 and 1939, Siegfried Schopflocher twice in the 1920s and again in 1936, Keith Ransom-Kehler in 1931–32, and Loulie Mathews in 1934. Accounts of their travels appeared in various Bahá’í publications, forging links between America and the antipodes.

Distinguished Bahá’í travelers from North America assisted the Dunns with the process of gaining media attention and expanding the Bahá’í communities of Australia and New Zealand in their formative years: Martha Root in 1924 and 1939, Siegfried Schopflocher twice in the 1920s and again in 1936, Keith Ransom-Kehler in 1931–32, and Loulie Mathews in 1934. Accounts of their travels appeared in various Bahá’í publications, forging links between America and the antipodes.

In early 1932 Clara Dunn made a pilgrimage to the Bahá’í holy places in Mandatory Palestine, remaining there for two months. She had hoped until the last moment that Hyde might accompany her, but he stayed behind, working “to enable her to go.” Shoghi Effendi received her with loving encouragement and revived her spirits. “Since going to Haifa,” she wrote in 1933, “I find I have fresh courage to go on. I was almost in despair as the Cause was not growing.” Shoghi Effendi stressed to Clara the necessity of forming a National Assembly in the antipodes. This was achieved in 1934, with delegates to a national Bahá’í convention coming from the Adelaide, Sydney, and Auckland Assemblies. Hyde served on the National Spiritual Assembly of Australia and New Zealand during its first year.

Shoghi Effendi had great affection for Hyde Dunn, to whom he referred in God Passes By, his history of the first century of the Bahá’í Faith, as “great-hearted and heroic.” In The Advent of Divine Justice, a long letter addressed to the North American Bahá’ís in 1939, he included the Dunns among a small band of distinguished North Americans who had won “eternal distinction” as the first Bahá’ís in a number of “highly important and widely scattered centers and territories.” Those who became Bahá’ís after hearing the Dunns speak numbered more than one hundred. They, in turn, assisted in firmly establishing Bahá’í communities throughout the South Pacific; such notable individuals as Gretta Lamprill, Bertha Dobbins, and Harold and Florence Fitzner became Bahá’ís in the 1920s through Clara and Hyde Dunn and later were designated “Knights of Bahá’u’lláh” by Shoghi Effendi for having been among the first to take the Bahá’í Faith to goal countries and territories in the Ten Year Plan (1953–63), a worldwide plan of expansion.

By 1932, when Nestlé retired Hyde, he had worked for some twelve years in Australia. He suffered a stroke in 1935 but gradually regained his general health, although his eyesight deteriorated. He continued to use his typewriter, however, even after he could no longer read what he had written. He died in Sydney on February 17, 1941. Shoghi Effendi eulogized “BELOVED FATHER DUNN” as “Australia’s spiritual conqueror” and observed in a cablegram that “MAGNIFICENT CAREER VETERAN WARRIOR FAITH BAHÁ’U’LLÁH REFLECTS PUREST LUSTER WORLD HISTORIC MISSION CONFERRED AMERICAN COMMUNITY BY ‘ABDU’L-BAHÁ.” In 1952 Shoghi Effendi posthumously designated Hyde Dunn a Hand of the Cause of God.

Clara Dunn after Hyde Dunn’s Death:

Clara had always regarded Hyde as the better speaker; but, after his death, the Bahá’ís turned to her and fully expected her to speak in his stead. Rising to the challenge, she invariably began her talks with a question often asked by ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, “Do you know in what day you are living?” In later years her speech was suffused with supplication, as she frequently recited prayers aloud, including her favorite by ‘Abdu’l-Bahá that began “O Lord, my God and my Haven in my distress!”

Clara had always regarded Hyde as the better speaker; but, after his death, the Bahá’ís turned to her and fully expected her to speak in his stead. Rising to the challenge, she invariably began her talks with a question often asked by ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, “Do you know in what day you are living?” In later years her speech was suffused with supplication, as she frequently recited prayers aloud, including her favorite by ‘Abdu’l-Bahá that began “O Lord, my God and my Haven in my distress!”

When the National Assembly called for pioneer teachers to establish the Bahá’í Faith in various locations at the start of a new phase of teaching in 1943, Clara settled in Brisbane for several months. Subsequently, she recommenced visiting major centers, a practice that she and Hyde had been unable to continue during the last years of Hyde’s life. She spent a year in Adelaide and visited the Bahá’ís in Melbourne, Hobart, and Newcastle as well as numerous smaller towns. She always suspended her travels in late December and early January to participate in summer schools at the Bahá’í property at Yerrinbool, south of Sydney. She stayed as the school committee’s guest in a room adjacent to the Hyde Dunn Hall. Participants at many summer schools in the 1940s and 1950s were able to hear her recount how she met ‘Abdu’l-Bahá and tell of her many years of travel with Hyde.

On February 29, 1952 Clara Dunn was among a contingent of seven individuals appointed by Shoghi Effendi as Hands of the Cause of God. Well over eighty and growing increasingly frail, she gathered her strength to fulfill her far-reaching spiritual and administrative responsibilities. In 1953, at the start of the Ten Year Plan, Shoghi Effendi directed her to travel among the Bahá’í communities in New Zealand and in Australia, where she settled for a time in Newcastle. In October 1953 she attended an intercontinental conference in New Delhi. In April 1954 Shoghi Effendi named her Trustee for the Continental Fund for Australasia. At the same time, he requested that she designate two individuals as members of the newly established Auxiliary Boards. On the occasion of the national Bahá’í convention, she appointed H. Collis Featherstone, whom Shoghi Effendi subsequently named a Hand of the Cause, and Thelma Perks, who was among those first appointed to the Continental Boards of Counselors when the Universal House of Justice established that institution in 1968. Both assisted Clara Dunn greatly in her duties, often writing reports to Shoghi Effendi on her behalf. A companion on many interstate visits, Thelma Perks had acted as a daughter to the Dunns from as early as the 1940s, even before she became a Bahá’í, and was well equipped to assist Clara in her work as a Hand of the Cause.

She placed in the foundation plaster from the fortress of Mákú, where the Báb was imprisoned for nine months.

Clara received direction from the Hands of the Cause of God residing in the Holy Land, who served as liaison between the Hands in the continents and Shoghi Effendi. Their letters explained which activities Shoghi Effendi felt were most important for her and her Auxiliary Board members to undertake in the period immediately ahead. In June 1954, for example, she was informed that during the second phase of the Ten Year Plan, which was to last from 1954 to 1956, the major tasks to be accomplished—and to which she and the Auxiliary Board members should lend their support—included acquiring sites for Bahá’í Temples, called Mashriqu’l-Adhkárs (the Sydney site had already been purchased), and for national administrative centers (Hazíratu’l-Quds), including one in Auckland and another in Suva, Fiji; maintaining current achievements; increasing the number of Bahá’í centers; expanding the scope of literature; purchasing national endowments; incorporating Assemblies; and establishing publishing trusts.

Clara received direction from the Hands of the Cause of God residing in the Holy Land, who served as liaison between the Hands in the continents and Shoghi Effendi. Their letters explained which activities Shoghi Effendi felt were most important for her and her Auxiliary Board members to undertake in the period immediately ahead. In June 1954, for example, she was informed that during the second phase of the Ten Year Plan, which was to last from 1954 to 1956, the major tasks to be accomplished—and to which she and the Auxiliary Board members should lend their support—included acquiring sites for Bahá’í Temples, called Mashriqu’l-Adhkárs (the Sydney site had already been purchased), and for national administrative centers (Hazíratu’l-Quds), including one in Auckland and another in Suva, Fiji; maintaining current achievements; increasing the number of Bahá’í centers; expanding the scope of literature; purchasing national endowments; incorporating Assemblies; and establishing publishing trusts.

During the years after she became a Hand of the Cause, Clara Dunn lived in a flat at the National Hazíratu’l-Quds in Sidney. She traveled several times to visit the Bahá’ís of New Zealand. In 1954 she attended their summer school on the site of the present National Hazíratu’l-Quds in Henderson, planting a kauri tree that still graces the grounds; and in April 1957 she represented Shoghi Effendi when the Bahá’ís of New Zealand held their inaugural national convention and elected their first National Spiritual Assembly.

Physically fragile, Clara remained robust in spirit despite two major losses she suffered in 1957. First, her son, Allen, died. His troubled life had been a source of pain to Clara over the years. Shoghi Effendi sent his condolences and asked the Bahá’ís of Australia to make every effort to comfort and care for “the mother of their community.” Then, on 4 November 1957, Shoghi Effendi passed away suddenly. As he left no appointed successor, the burden of leadership fell upon the Hands of the Cause. Clara insisted on traveling to a meeting of the Hands held in Haifa later that month. Although she was too weak to attend the sessions, she participated by signing several major statements that the meeting produced.

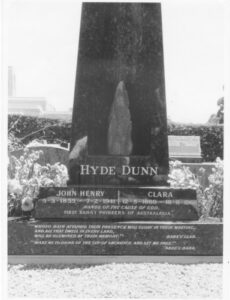

Graves of Clara and John Henry Hyde Dunn at Woronora Cemetery in metropolitan Sydney. National Bahá’í Archives, United States.

A few months later, Clara addressed an intercontinental Bahá’í conference held in Sydney on March 21 – 24, 1958, at which some three hundred Bahá’ís from nineteen countries gathered. On the second day of the conference, she played a major role in the foundation ceremony of the first Bahá’í House of Worship in Australasia, located on a hilltop in nearby Ingleside. For the next few years, she continued her activities as her health permitted, attending her last summer school at Yerrinbool in 1959 and her last Australian Bahá’í convention in April 1960.

Clara Dunn died in Sydney on November 18, 1960 and was buried beside her husband in Woronora Cemetery. The Hands of the Cause in the Holy Land, in announcing her death, paid tribute to her as a “DISTINGUISHED MEMBER” of the American Bahá’í community who responded to ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s call to take the Bahá’í Faith to the antipodes and who “RENDERED UNIQUE UNFORGETTABLE PIONEER SERVICE.”

Clara Dunn died in Sydney on November 18, 1960 and was buried beside her husband in Woronora Cemetery. The Hands of the Cause in the Holy Land, in announcing her death, paid tribute to her as a “DISTINGUISHED MEMBER” of the American Bahá’í community who responded to ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s call to take the Bahá’í Faith to the antipodes and who “RENDERED UNIQUE UNFORGETTABLE PIONEER SERVICE.”

Source:

Hassall, Graham “Dunn, Clara and Dunn, John Henry Hyde” Bahá’í Encyclopedia Project. bahai-encyclopedia-project.org

Images:

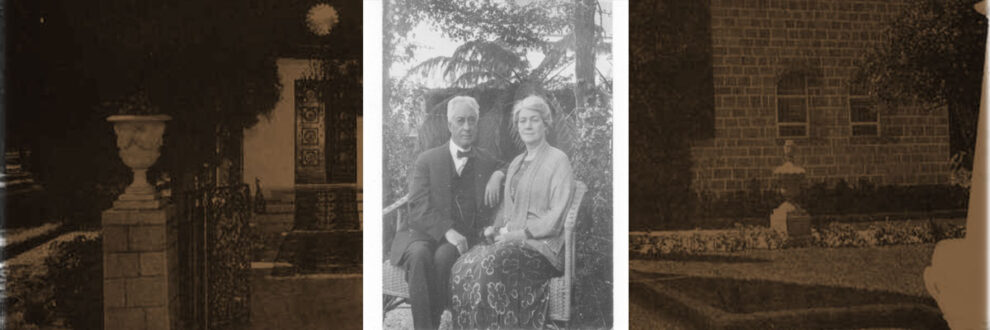

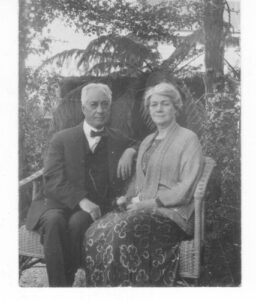

Hyde and Clara Dunn, Auckland, early 1920s. National Bahá’í Archives, United States