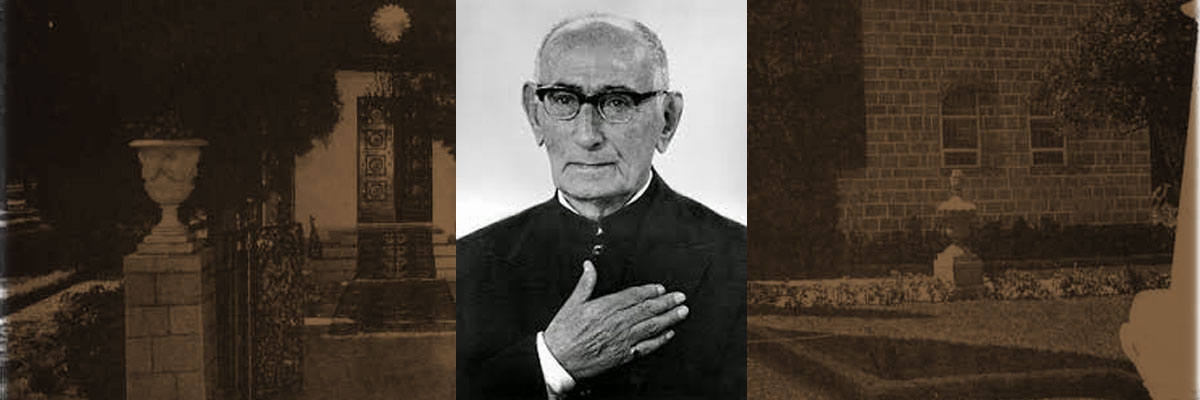

Siegfried Schopflocher

Siegfried Schopflocher

Born:September 26, 1877

Death: July 27, 1953

Place of Birth: Fürth, Bavaria, Germany

Location of Death: Montreal, Canada

Burial Location: Mount Royal Cemetery, Montreal, Canada

Canadian Bahá’í of German-Jewish background; named by Shoghi Effendi a Hand of the Cause of God in 1952.

Siegfried (“Fred” or “Freddie”) Schopflocher was born in Fürth, Bavaria, near Nuremberg, September 26, 1877, he was the youngest of eighteen (18) children. His parents, both lifelong residents of Fürth, were Salomon Schopflocher (1824–1903), a salesman, and Sara Goetz (1835–1908), daughter of Rabbi Joel Goetz. Little is known of Schopflocher’s childhood and youth. He attended university—probably in the city of Frankfurt, where he moved in July 1893—but did not finish his last year. Raised as an Orthodox Jew, he became an agnostic after leaving school and began an extended spiritual search. He also determined to succeed in business. He began working as a salesman-apprentice, apparently for his brothers Nathan and Julius, who had established a bronze and aluminum powder factory in Frankfurt.

Schopflocher crossed the Atlantic several times between 1900 and 1904. In 1906 he emigrated to Canada and settled in Montreal, where he first appears listed in a 1910 city directory. He founded the Canadian Bronze Powder Works in (Salaberry de) Valleyfield, Quebec, near Montreal. Later described as an “astute, hard-driving, forceful man of the business world,” Schopflocher was president of the firm, which eventually had affiliated bronze powder works in New York State and New Jersey and offices around the globe. A North American subsidiary of International Bronze Powder Works (headquartered in Germany) until that company was confiscated by the Nazi regime in the 1930s, the company then became known as International Bronze Powders Limited. Schopflocher held the world patent rights for bronze powder (used for coating objects to give them the color and luster of bronze or gold). Many years later, the firm he established would provide the powder used in the James Bond film Goldfinger (1964).

In January 1918 Schopflocher married Florence Evaline (known as “Lorol,” or “Laurel,” and by the nickname “Kitty”) Snyder (1886–1970), who was born and raised in Montreal but had lived at one time in New York City, where the wedding took place. The couple had no children. Most of Schopflocher’s large family died in Nazi concentration camps during World War II. Surviving relatives (descendants of his brothers and an uncle) live in Montreal and Edmonton in Canada and in Buenos Aires, Argentina.

A few years after Lorol and Fred Schopflocher married, Lorol met a Bahá’í named Rose Henderson in Montreal and found herself attracted to the Faith. When she was invited to Green Acre, the Bahá’í school and conference center in Eliot, Maine, Lorol took the opportunity to learn more about the religion. Fred, skeptical but willing to indulge his wife, agreed to accompany her. Both the Schopflochers became Bahá’ís at Green Acre in the summer of 1921.

A few months later, the couple journeyed to Mandatory Palestine to meet ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, but they arrived shortly after His passing in Haifa on November 28, 1921. According to an account by Rosemary Sala, a longtime friend, the visit to Haifa marked the beginning of Fred’s life as a Bahá’í. He had followed Lorol’s lead in investigating the Bahá’í Faith but had not shared her immediate enthusiasm. Even after becoming a Bahá’í, he had retained his skepticism about religion and resisted emotional commitment. During their visit to Haifa, however, Fred met Saichiro Fujita, the second Bahá’í of Japanese descent, who had become a Bahá’í in California in 1905, had traveled with ‘Abdu’l-Bahá in America, and had gone to Palestine in 1919 to serve at the Bahá’í World Center. Through Fujita, in a moment of immense spiritual emotion, Fred became confirmed in his faith.

In 1924 and 1925 Fred made return visits to Haifa to meet Shoghi Effendi, with whom he developed a close relationship. After their first meeting, Shoghi Effendi referred to him as “My beloved Fred, that living torch, lit by the spirit of our departed Master [‘Abdu’l-Bahá]” and as a “zealous and promising disciple of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá.” Shoghi Effendi readily recognized Schopflocher’s “clear understanding of, and entire devotion to, the interests” of the Bahá’í Faith, and Schopflocher gained a devotion to Shoghi Effendi that was “immediate and lasting.”

In 1924 and 1925 Fred made return visits to Haifa to meet Shoghi Effendi, with whom he developed a close relationship. After their first meeting, Shoghi Effendi referred to him as “My beloved Fred, that living torch, lit by the spirit of our departed Master [‘Abdu’l-Bahá]” and as a “zealous and promising disciple of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá.” Shoghi Effendi readily recognized Schopflocher’s “clear understanding of, and entire devotion to, the interests” of the Bahá’í Faith, and Schopflocher gained a devotion to Shoghi Effendi that was “immediate and lasting.”

Fred’s wealth and business connections, combined with Lorol’s skills as a speaker, offered the couple many ways to assist the new religion. Fred financed Lorol’s extensive travels throughout the world to promote the Bahá’í Faith, during which she was able to visit more than eighty countries. Lorol was one of a handful of Western women, including her close friend Keith Ransom-Kehler, who attempted to alleviate the persecutions of the Bahá’ís in Iran. She visited the country several times during the 1920s.

Fred’s travels were no less widespread than those of his wife. From the moment he met Shoghi Effendi, Schopflocher not only carried out specific assignments given to him by Shoghi Effendi but also journeyed to many parts of the world. His trips were undertaken primarily for business, but they provided opportunities for him to visit Bahá’í communities, which often organized public meetings at which he spoke. He was also able to discuss the Bahá’í Faith with some of the people he met. Schopflocher traveled to Europe, Latin America (Brazil, Argentina, Chile, Peru, Panama, Costa Rica), the South Pacific (New Zealand, Australia), and Asia (the Philippines, Hong Kong, China, Japan, Burma, India). The North American journal Bahá’í Magazine: Star of the West published several of Schopflocher’s travel accounts, filled with ethnographic details of places he visited and stories of his encounters with people interested in the Bahá’í Faith.

Because of his prominence and integrity as an industrialist, Schopflocher was highly regarded by his business associates in many lands. The Bahá’ís he met in his travels found him to be, as he was described in a 1936 letter written on Shoghi Effendi’s behalf, “truly one of the most distinguished believers in the West.” They benefited from the practical experience and perspectives Schopflocher shared in question-and-answer sessions and other meetings. In Sydney, Australia, in 1936, for example, he discussed with the Local Spiritual Assembly community issues, including “fostering the community spirit through properly organized socials as the test of Bahá’ís was their ability to associate together in love and harmony,” and he visited the property at Yerrinbool that was to become a Bahá’í school.

When not traveling, Fred and Lorol Schopflocher maintained a busy life in Montreal, where they were deeply involved in local Bahá’í activities. They also owned a cottage at Green Acre (Ole Bull Cottage) and a nearby farm called Nine Gables.

Schopflocher made a number of remarkable contributions to the development of the North American Bahá’í community. The most enduring relates to the building of the Bahá’í House of Worship in Wilmette, Illinois (See Mashriqu’l-Adhkár.Houses of Worship around the World.Chicago). Through his visits to Shoghi Effendi, he realized the importance of this project for the growth of the Bahá’í Faith and made several large donations to the Temple fund. A 1936 letter written on Shoghi Effendi’s behalf states that “it was mainly due to his [Schopflocher’s] unfailing and most generous assistance that the Temple in Wilmette was built.” In addition to making direct contributions, he was able to generate fresh enthusiasm for resumption of work on the Temple’s exterior ornamentation during the Great Depression of the 1930s. Another 1936 letter written on Shoghi Effendi’s behalf asserts that Schopflocher’s name will “ever be associated” with the Wilmette Temple: “Had it not been for the continued and wholehearted support, both financial and moral, which he so generously extended to it, that edifice could never have been reared so steadily and efficiently.”

Schopflocher was also deeply interested in developing Green Acre. He once told a gathering that, when looking at the Green Acre buildings during his first visit there in 1921, he said to himself, “Freddie, if you become a Bahá’í, it’s going to cost you a lot of money. Well, I did, and it did!” His contributions to Green Acre, “the sacrifice of . . . time, energy and money” which Shoghi Effendi commended, made possible both improvements and repairs. Schopflocher donated several important properties that are now part of the school, including a cottage that still bears his name. He also gave attention and financial support to Geyserville Bahá’í School in northern California.

In 1941 the imposition of Canadian wartime currency exchange regulations limited the amount of money that residents could take out of the country, making it impossible for Canadian Bahá’ís to attend summer schools in the United States. Schopflocher provided the material means to arrange for such institutions in Canada. A much cherished gift in 1947 was the donation, in cooperation with Canadian Bahá’ís Emeric and Rosemary Sala, of a permanent Bahá’í school property called Beaulac, located north of Montreal. For more than two decades, this school was one of the chief means by which groups of Bahá’ís from central and eastern Canada could study the Bahá’í Faith together.

Eager to assist Shoghi Effendi, Schopflocher helped to subsidize publication of The Bahá’í World, a series of reference volumes on the Bahá’í Faith and its international activities that were prepared under Shoghi Effendi’s supervision and in which he took a keen interest. Schopflocher sent bronze powder for use in another activity to which Shoghi Effendi devoted close personal attention: the beautification of the Bahá’í World Center, including the gates before the entrance door of the Shrine of Bahá’u’lláh. Mindful even of small needs, Schopflocher supplied the beautifully embossed notes used in the Guardian’s official correspondence.

Schopflocher’s administrative contributions were extensive and varied. He served on the National Spiritual Assembly of the Bahá’ís of the United States and Canada, the chief governing council in North America (See Administration, Bahá’í.Institutions of Bahá’í Administration.National Spiritual Assemblies), for fifteen years: 1924–27, 1929–35, and 1938–44 (when he was also the body’s assistant treasurer). He was a member and the treasurer of the National Spiritual Assembly of Canada from its inception in 1948 until April 1953, shortly before his death. As the assembly’s treasurer, Schopflocher made a special point of writing affectionate notes of appreciation with every receipt. He was, moreover, careful that his own generous contributions did not stifle the participation of Bahá’ís in giving to the Bahá’í Fund.

Schopflocher played the crucial role in achieving the incorporation of the Canadian National Assembly by a special Act of Parliament in April 1949—an achievement twice hailed by Shoghi Effendi as “a unique victory in the annals of the Faith in the East, and West.” In 1952 Shoghi Effendi requested Schopflocher to assist the National Spiritual Assembly of Canada in establishing its National Bahá’í Center.

Schopflocher was on pilgrimage in Haifa in January 1952, shortly after Shoghi Effendi took a major step in developing the Hands of the Cause of God—an administrative institution established by Bahá’u’lláh—by appointing twelve individuals from around the world to serve as Hands. Schopflocher and fellow pilgrim Musa Banani, an Iranian residing in Africa, both heard from Shoghi Effendi himself the stunning news that he was appointing a second contingent of seven and that they would be among those named. Shoghi Effendi made the announcement to the Bahá’ís of the world on February 29, 1952.

Schopflocher traveled widely in Canada as a Hand of the Cause, speaking about Shoghi Effendi’s work and vision. In late April and early May 1953, Schopflocher attended the dedication of the Wilmette Temple, to which he had made such outstanding contributions, and an All-America Intercontinental Teaching Conference held in Chicago immediately following the dedication. He traveled to the Bahá’í World Center in the summer of 1953 and looked forward to revisiting India to attend the New Delhi Bahá’í Intercontinental Conference in October. Unfortunately, however, he became ill while returning to Montreal from Haifa. At home, his condition quickly worsened, and he passed away at 9:30 AM on July 27, 1953. He was buried near the grave of Hand of the Cause of God Sutherland Maxwell in the Mount Royal Cemetery in Montreal. A cabled message from Shoghi Effendi reads in part:

Profoundly grieved at passing of dearly loved, outstandingly staunch Hand of Cause Fred Schopflocher. His numerous, magnificent services extending over thirty years in administrative and teaching spheres for United States, Canada, Institutions at Bahá’í World Center greatly enriched annals of Formative Age of Faith. Advising American National Assembly to hold befitting memorial gathering at Temple he generously helped raise. Advise holding memorial gathering at Maxwell home to commemorate his eminent part in rise of Administrative Order of Faith in Canada.

Many accounts attest to Schopflocher’s distinguished personal characteristics. After meeting Schopflocher for the first time in 1924, Shoghi Effendi wrote the Bahá’ís of Canada, “In my hours of association with your beloved representative I could not but feel deeply impressed by the sweetness of his nature, his ardour, his humility and selflessness.” The qualities Shoghi Effendi identified pervaded Schopflocher’s nature and remained unchanged by time and personal tragedy; the loss of much of his family during the Holocaust neither embittered nor hardened him.

An unobtrusive person, Schopflocher demonstrated a deep humility. One early Bahá’í recounts that, noting his “battered hat” and unassuming manner when he greeted her at the door of his mansion at 1904 Van Horne Avenue in Montreal, she mistook him for the janitor or doorman. In a second misunderstanding, thinking he was a grandfather, she had brought candy for his grandchildren. He corrected her impression and accepted the candy with grace, as if he had never before received a gift, saying that people expected him, as a millionaire, to give gifts, not receive them.

The Sunday brunches in his home became for many Bahá’ís a source of learning about love and service to others. By providing a taxi for anyone who needed it, Schopflocher always made sure that no Bahá’í, whatever the weather conditions in Montreal, would be deprived of attending. His great generosity benefited both the Bahá’í Cause and many individuals.

Schopflocher conveyed a spirit of egalitarianism that profoundly impressed those who came into contact with him. When making his customary three-day business trips from Montreal to his powder works in Malone, New York, he preferred to ride in the baggage car, playing cribbage with the railway workers. A number of railway workers and border guards attended his funeral.

Punctuality was a distinguishing feature of Schopflocher’s interactions with others. He was never late for a meeting and was often heard to say that he would rather be ten minutes early than one minute late.

John Robarts, a colleague on the National Spiritual Assembly of Canada in 1952 who was later also appointed a Hand of the Cause, recounted a memorable example of Schopflocher’s unassuming nature. On returning from his pilgrimage in 1952, after having learned of his appointment as a Hand but before the official announcement had been made, Schopflocher had attended a National Assembly meeting without mentioning his appointment. Later, after learning of the announcement, Robarts asked why Schopflocher had not shared the news with the Assembly. Schopflocher replied that it had not seemed important enough to mention.

Without ever allowing his station as a Hand of the Cause to diminish his deep humility, Schopflocher brought to his Bahá’í associations a clear appreciation of the institutions of the Guardianship and the Hands of the Cause of God. He was not a polished speaker, but his bearing and a “beautiful light” that “filled his eyes” made him seem eloquent. He inspired by his mere presence. Asked to address the Canadian national Bahá’í convention in April 1953 about what it meant to be a Hand of the Cause, Schopflocher spoke movingly, “the words . . . rising from the depths of his heart till he had all eyes filled with tears of deep feeling.” Finally, he began saying, “And the Guardian said . . .” but, with tears coursing down his cheeks, was unable to finish his talk.

A year after Schopflocher’s death, a letter written on Shoghi Effendi’s behalf to the National Spiritual Assembly of Canada paid tribute to the strengths of character that Schopflocher had demonstrated for more than three decades: “The loss of the dear Hand of the Cause, Freddie Schopflocher, is going to be much felt. He was so intensely loyal, so vigilant in watching over the interests of the Faith, so steadfast and tenacious in serving it, that he will be much missed. . . .”

Source:

van den Hoonaard, Will C. “Siegfried Schopflocher” Bahá’í Encyclopedia Project. bahai-encyclopedia-project.org

Images:

Baha’i World Centre Archives