Báb, Forerunner of Bahá’u’lláh

Born: October 20, 1819

Death: July 9, 1850

Place of Birth: Shiraz, Iran

Location of Death: Tabriz, Iran

Burial Location: Shrine of the Báb on Mount Carmel, Haifa, Israel

“His life is one of the most magnificent examples of courage which it has been the privilege of mankind to behold…”[1] The object of this tribute by the prominent French writer A.L.M. Nicolas was the nineteenth century prophetic figure known to history as the Báb.

Millenial fervor gripped many peoples throughout the world during the first half of the nineteenth century; while Christians expected the return of Christ, a wave of expectation swept through Islam that the “Lord of the Age” would appear. Both Christians and Muslims envisioned that, with fulfillment of the prophecies in their scriptures, a new spiritual age was about to begin.

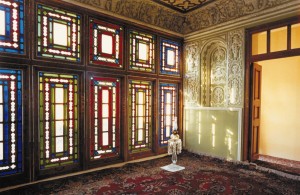

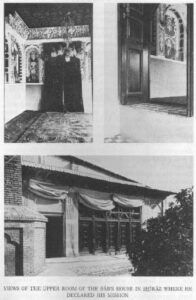

In Persia, this messianic ferment reached a dramatic climax on May 23, 1844, when a young merchant–the Báb–announced that He was the Bearer of a long-promised Divine Revelation destined to transform the spiritual life of the human race.

“O peoples of the earth,” the Báb declared, “Give ear unto God’s holy Voice…Verily the resplendent Light of God hath appeared in your midst, invested with this unerring Book, that ye may be guided aright to the ways of peace…”[2]

Against a backdrop of widescale moral breakdown in Persian society, the Báb’s declaration that spiritual renewal and social advancement rested on “love and compassion” rather “than force and coercion,” aroused hope and excitement among all classes, and He quickly attracted thousands of followers.[3]

Although the young merchant’s given name was Siyyid ‘Ali-Muhammad, He took the  name “Báb,” a title that means “Gate” or “Door” in Arabic. His coming, the Báb explained, represented the portal through which the universally anticipated Revelation of God to all humanity would soon appear. The central theme of His major work–the Bayan–was the imminent appearance of a second Messenger from God, one Who would be far greater than the Báb, and Whose mission would be to usher in the age of peace and justice promised in Islam, Judaism, Christianity, and all the other world religions.

name “Báb,” a title that means “Gate” or “Door” in Arabic. His coming, the Báb explained, represented the portal through which the universally anticipated Revelation of God to all humanity would soon appear. The central theme of His major work–the Bayan–was the imminent appearance of a second Messenger from God, one Who would be far greater than the Báb, and Whose mission would be to usher in the age of peace and justice promised in Islam, Judaism, Christianity, and all the other world religions.

The Báb referred to this coming Divine Teacher as “Him Whom God shall make manifest” and stated that “no words of Mine can adequately describe Him, nor can any reference in My Book, the Bayan, do justice to His Cause.”[4]

The Báb referred to this coming Divine Teacher as “Him Whom God shall make manifest” and stated that “no words of Mine can adequately describe Him, nor can any reference in My Book, the Bayan, do justice to His Cause.”[4]

He clarified the central aim of His mission by explaining that “the purpose underlying this Revelation, as well as those that preceded it, has, in like manner, been to announce the advent of the Faith of Him Whom God will make manifest.”[5] The basis for all human accomplishment is to be found in the teachings of this promised universal Manifestation of God, and “the sum total of the religion of God is but to help Him.”[6] For the Báb, a climacteric in human history had been reached, and He was the “Voice of the Crier, calling aloud in the wilderness of the Bayan” announcing to humanity that it was entering the period of its collective maturity.[7]

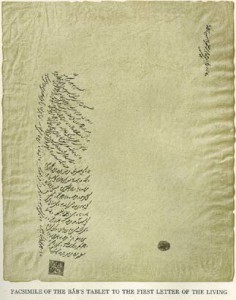

Throughout His writings, the Báb warned His followers to be watchful, and as soon as the promised Teacher revealed Himself, to recognize and follow Him. The Báb exhorted them to see with the “eye of the spirit” rather than through their “fanciful imaginations.”[8] To be worthy of “Him Whom God shall make manifest” required entirely new standards of conduct, a nobility of character that human beings had theretofore not achieved: “Purge your hearts of worldly desires,” the Báb urged His first group of disciples, “and let angelic virtues be your adorning…The time is come when naught but the purest motive, supported by deeds of stainless purity, can ascend to the throne of the Most High and be acceptable unto Him…”[9]

In several instances the Báb alluded to the identity of the Promised One: “Well is it with him who fixeth his gaze upon the Order of Bahá’u’lláh and rendereth thanks unto his Lord. For He will assuredly be made manifest.”[10] And: “When the Day-Star of Baha will shine resplendent above the horizon of eternity it is incumbent upon you to present yourselves before His Throne.”[11] Husayn-`Ali, a leading disciple of the Báb known to history as Bahá’u’lláh, assumed the title of “Baha” (Arabic for “glory” or “splendor”) at a gathering of the Báb’s followers in 1848, a title that was later confirmed by the Báb Himself.

In some respects, the Báb’s role can be compared to that of John the Baptist in the founding of Christianity. The Báb was Bahá’u’lláh’s herald: His principal mission was to prepare the way for Bahá’u’lláh’s coming. Accordingly, the founding of the Bábi Faith is viewed by Bahá’ís as synonymous with the founding of the Bahá’í Faith–and its purpose was fulfilled when Bahá’u’lláh announced in 1863 that He was the Promised One foretold by the Báb. Bahá’u’lláh later affirmed that the Báb was “the Herald of His Name and the Harbinger of His Great Revelation which hath caused…the splendour of His light to shine forth above the horizon of the world.”[12] The Báb’s appearance marked the end of the “Prophetic Cycle” of religious history, and ushered in the “Cycle of Fulfillment.”

At the same time, however, the Báb founded a distinctive, independent religion of His own. Known as the Bábi Faith, that religious dispensation produced its own vigorous community, its own scriptures, and left its own indelible mark on history. The Bahá’í writings attest that “the greatness of the Báb consists primarily, not in His being the divinely-appointed Forerunner of so transcendent a Revelation, but rather in His having been invested with the powers inherent in the inaugurator of a separate religious Dispensation, and in His wielding, to a degree unrivaled by the Messengers gone before Him, the scepter of independent Prophethood.”[13] With His call for the spiritual and moral reformation of Persian society, and His insistence upon the upliftment of the station of women and the poor, the Báb indeed assumed a position reminiscent of the Prophets of the past. But unlike those Seers of old who could but look to the far future for the time when “the earth shall be filled with the knowledge of the glory of the Lord,”[14] the Báb by His very appearance signified that the dawn of the “Day of God” had at last arrived.

The hearts and minds of those who heard the message of the Báb were locked in a mental world that had changed little from medieval times. Along with His prescription for spiritual renewal, His promotion of education and the useful sciences was by any measure revolutionary. Thus, by proclaiming an entirely new religion, the Báb was able to help His followers break free from the Islamic frame of reference and to mobilize them in preparation for the coming of Bahá’u’lláh.

Mulla Husayn-i-Bushrú’i, a member of Persia’s religious class, described the effect on him of his first meeting with the Báb: “I felt possessed of such courage and power that were the world, all its peoples and its potentates, to rise against me, I would alone and undaunted, withstand their onslaught. The universe seemed but a handful of dust in my grasp. I seemed to be the Voice of Gabriel personified, calling unto all mankind: ‘Awake, for, lo! the morning Light has broken.'”[15]

The transformative impact of the Báb’s message was primarily achieved through the dissemination of His epistles, commentaries, and doctrinal and mystical works. Some, though, like Mulla Husayn, were able to hear Him directly. The effect of the Báb’s voice was described by one of His followers: “The melody of His chanting, the rhythmic flow of the verses which streamed from His lips caught our ears and penetrated into our very souls. Mountain and valley re-echoed the majesty of His voice. Our hearts vibrated in their depths to the appeal of His utterance.”[16]

The boldness of the Báb’s proclamation–which put forth the vision of an entirely new society–stirred intense fear within the religious and secular establishments. Accordingly, persecution of the Bábis quickly developed. Thousands of the Báb’s followers were put to death in a horrific series of massacres. The extraordinary moral courage evinced by the Bábis in the face of this onslaught was recorded by a number of Western observers. European intellectuals such as Ernest Renan, Leo Tolstoy, Sarah Bernhardt and the Comte de Gobineau were deeply affected by this spiritual drama that had unfolded in what was regarded as a darkened land. The nobility of the Báb’s life and teachings and the heroism of His followers became a frequent topic of conversation in the salons of Europe. The story of Tahirih, the great poet and Bábi heroine, who declared to her persecutors, “You can kill me as soon as you like, but you cannot stop the emancipation of women,” traveled as far and as quickly as that of the Báb Himself.[17]

Ultimately, those opposed to the Báb argued that He was not only a heretic, but a dangerous rebel. The authorities decided to have Him executed. On 9 July 1850, this sentence was carried out, in the courtyard of the Tabriz army barracks. Some 10,000 people crowded the rooftops of the barracks and houses that overlooked the square. The Báb and a young follower were suspended by two ropes against a wall. A regiment of 750 Armenian soldiers, arranged in three files of 250 each, opened fire in three successive volleys. So dense was the smoke raised by the gunpowder and dust that the entire yard was obscured.

Ultimately, those opposed to the Báb argued that He was not only a heretic, but a dangerous rebel. The authorities decided to have Him executed. On 9 July 1850, this sentence was carried out, in the courtyard of the Tabriz army barracks. Some 10,000 people crowded the rooftops of the barracks and houses that overlooked the square. The Báb and a young follower were suspended by two ropes against a wall. A regiment of 750 Armenian soldiers, arranged in three files of 250 each, opened fire in three successive volleys. So dense was the smoke raised by the gunpowder and dust that the entire yard was obscured.

report of the execution, written to Lord Palmerston, the British Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, by Sir Justin Shiel, Queen Victoria’s Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary in Tehran on July 22, 1850, records: “When the smoke and dust cleared away after the volley, Báb was not to be seen, and the populace proclaimed that he had ascended to the skies. The balls had broken the ropes by which he was bound but he was dragged from the recess where, after some search he was discovered and shot.”[18] After the first attempt at execution, the Báb was found back in His cell, giving final instructions to one of His followers. Earlier in the day, when the guards had come to take Him to the courtyard, the Báb had warned that no “earthly power” could silence Him until He had finished all that He had to say. When the guards arrived this second time, the Báb calmly announced: “Now you may proceed to fulfill your intention.”[19]

report of the execution, written to Lord Palmerston, the British Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, by Sir Justin Shiel, Queen Victoria’s Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary in Tehran on July 22, 1850, records: “When the smoke and dust cleared away after the volley, Báb was not to be seen, and the populace proclaimed that he had ascended to the skies. The balls had broken the ropes by which he was bound but he was dragged from the recess where, after some search he was discovered and shot.”[18] After the first attempt at execution, the Báb was found back in His cell, giving final instructions to one of His followers. Earlier in the day, when the guards had come to take Him to the courtyard, the Báb had warned that no “earthly power” could silence Him until He had finished all that He had to say. When the guards arrived this second time, the Báb calmly announced: “Now you may proceed to fulfill your intention.”[19]

Again, the Báb and His young companion were brought out for execution. The Armenian troops refused to fire, and a Muslim firing squad was assembled and ordered to shoot. This time the bodies of the pair were shattered, their bones and flesh mingled into one mass. Surprisingly, their faces were untouched. The light of the “Mystic Fane,” as the Báb referred to Himself, had been quenched under a dramatic set of circumstances.[20] The last words of the Báb to the crowd were: “O wayward generation! Had you believed in Me every one of you would have followed the example of this youth, who stood in rank above most of you, and would have willingly sacrificed himself in My path. The day will come when you will have recognized Me; that day I shall have ceased to be with you.”[21]

Again, the Báb and His young companion were brought out for execution. The Armenian troops refused to fire, and a Muslim firing squad was assembled and ordered to shoot. This time the bodies of the pair were shattered, their bones and flesh mingled into one mass. Surprisingly, their faces were untouched. The light of the “Mystic Fane,” as the Báb referred to Himself, had been quenched under a dramatic set of circumstances.[20] The last words of the Báb to the crowd were: “O wayward generation! Had you believed in Me every one of you would have followed the example of this youth, who stood in rank above most of you, and would have willingly sacrificed himself in My path. The day will come when you will have recognized Me; that day I shall have ceased to be with you.”[21]

Bahá’u’lláh paid this tribute to the Báb: “Behold what steadfastness that Beauty of God hath revealed. The whole world rose to hinder Him, yet it utterly failed. The more severe the persecution they inflicted on that Sadrih [Branch] of Blessedness, the more His fervour increased, and the brighter burned the flame of His love. All this is evident, and none disputeth its truth. Finally, He surrendered His soul, and winged His flight unto the realms above.”[22]

A.L.M. Nicolas, who chronicled the episode of the Báb, wrote: “He sacrificed himself for humanity; for it he gave his body and his soul, for it he endured privations, insults, torture and martyrdom. He sealed, with his very lifeblood, the covenant of universal brotherhood. Like Jesus he paid with his life for the proclamation of a reign of concord, equity, and brotherly love.”[23]

The short six-year duration of the Báb’s mission in some respects symbolized the abrupt and startling transition to global consciousness that the Báb had called humanity to undertake. Since His bold proclamation in the middle of the last century, unparalleled scientific and technological advances have indeed provided the first glimmerings of a global society. In His role as the “Primal Point from which have been generated all created things,” the Báb set in motion a dramatic new cycle of human creativity and discovery.[24] The “breezes” of God’s “knowledge” had “stirred” the “minds of men” and caused “the spirits to soar.”

The short six-year duration of the Báb’s mission in some respects symbolized the abrupt and startling transition to global consciousness that the Báb had called humanity to undertake. Since His bold proclamation in the middle of the last century, unparalleled scientific and technological advances have indeed provided the first glimmerings of a global society. In His role as the “Primal Point from which have been generated all created things,” the Báb set in motion a dramatic new cycle of human creativity and discovery.[24] The “breezes” of God’s “knowledge” had “stirred” the “minds of men” and caused “the spirits to soar.”

The nearly simultaneous appearance of two Manifestations of God, Bahá’u’lláh Himself states, “is a mystery such as no mind can fathom.”[25] For Bahá’ís, it is both an affirmation that the establishment of universal peace–the “Kingdom of God”–is not too far distant, and a testimony to the greatness of Bahá’u’lláh’s Revelation. As `Abdu’l-Bahá, Bahá’u’lláh’s appointed successor, explains:

The Báb, the Exalted One, is the Morn of Truth, the splendor of Whose light shineth throughout all regions. He is also the Harbinger of the Most Great Light, the Abha Luminary (Bahá’u’lláh). The Blessed Beauty (Bahá’u’lláh) is the One promised by the sacred books of the past, the revelation of the Source of light that shone upon Mount Sinai, Whose fire glowed in the midst of the Burning Bush. We are, one and all, servants of their threshold, and stand each as a lowly keeper at their door.[26]

Source:

1 A.L.M. Nicolas, Siyyid Ali-Muhammad dit le Báb (Paris: Librairie Critique, 1908), pp. 203-4, 376. Quoted in The Dawnbreakers, p. 515 (footnote)

2 Selections from the Writings of the Báb (Haifa: Bahá’í World Centre, 1976), p. 50, 61

3 Ibid., p. 77.

4 Shoghi Effendi, The World Order of Bahá’u’lláh, 2d rev. ed. (Wilmette: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1974), p. 62.

5 Selections from the Writings of the Báb, p. 106.

6 Ibid, p. 85.

7 Bahá’u’lláh, Tablets of Bahá’u’lláh Revealed after the Kitab-i-Aqdas (Wilmette: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1995), p. 12.

8 Selections from the Writings of the Báb, p. 146.

9 Muhammad-i-Zarandi (Nabil-i-Azam), The Dawn-Breakers: Nabil’s Narrative of the Early Days of the Bahá’í Revelation, translated from the Persian by Shoghi Effendi (1932; reprint, Wilmette: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1974), p. 93.

10 The World Order of Bahá’u’lláh, p. 147.

11 Selections from the Writings of the Báb, p. 164.

12 Tablets of Bahá’u’lláh, p. 102.

13 The World Order of Bahá’u’lláh, p. 123.

14 Isaiah 11:9

15 The Dawn-Breakers, p. 65.

16 Ibid., p. 251.

17 Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By (Wilmette, Il: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1944), p. 75.

18 Quoted in John Ferraby, All Things Made New: A Comprehensive Outline of the Bahá’í Faith (London: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, revised edition 1975), p. 199.

19 The Dawn-Breakers, p. 463.

20 Selections from the Writings of the Báb, p. 74.

21 The Dawn-Breakers, p. 464.

22 Bahá’u’lláh, The Book of Certitude, 3d ed. (Wilmette: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1982), p. 234.

23 A.L.M. Nicolas, see note 1.

24 The World Order of Bahá’u’lláh, p. 126.

25 Ibid., p. 124.

26 Ibid., p. 127.

Images:

Bahainews.ca: Declaration of the Báb Room

bahaisacredrelics.blogspot.com: The Báb’s Tablet to the First Letter of the Living Mulla Husayn

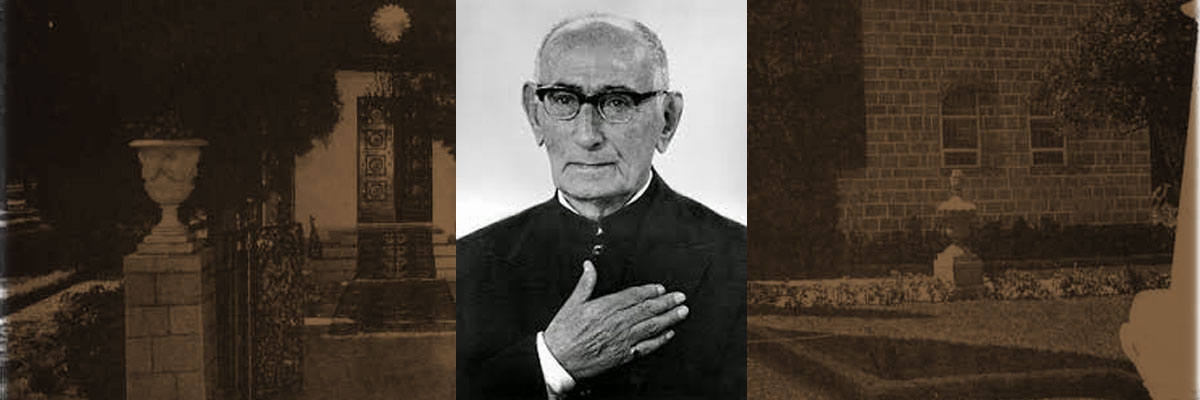

Baha’i World Centre Archives

Dawn Breakers – Chapter 3

(c) Baha’i Chronicles