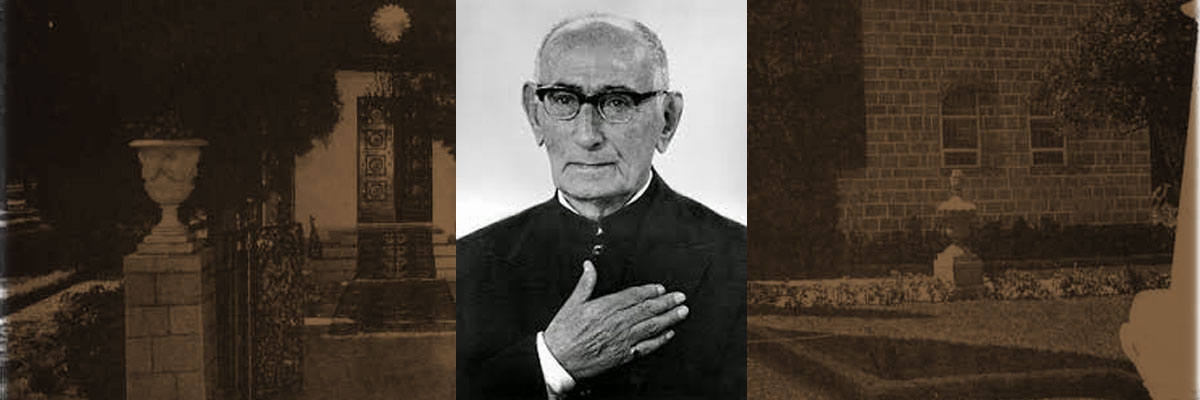

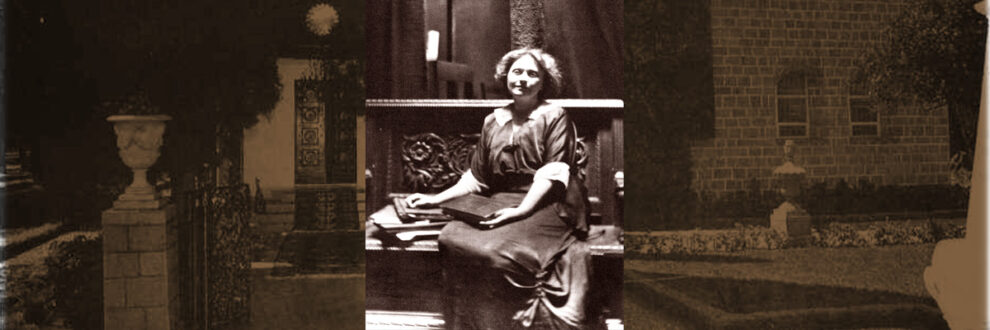

Juliet Thompson

Juliet Thompson

Born: September 23, 1873

Death: December 9, 1956

Place of Birth: Washington, D.C.

Location of Death: New Rochelle, New York

Burial Location: Beechwoods Cemetery, New Rochelle, New York – Plot 993 Section 20

At an early age Juliet became interested in painting. She studied at the Corcoran Art School in Washington and at seventeen was doing portraits in pastels professionally. By the middle 1890’s, when in her early twenties, she had already made a name for herself.

Around the turn of the century the mother of Laura Clifford Barney invited the young artist to come to Paris for further study. Juliet went accompanied by her mother and brother.

It was there that she met May Bolles – the first Bahá’í on the European continent – and through her, accepted this new Faith. Mrs. Barney wrote of Juliet that she had accepted it “as naturally as a swallow takes to the air.”

Juliet became one of that first group of Paris Bahá’ís, which included Mrs. Barney. Enthusiasm and activity were at a high point, partly because of the presence of Mirza Abu’l-Fadl, whom ‘Abdu’l-Baha had sent to France. His lessons, together with May Bolles’ influence, were very confirming to Juliet, and the process was completed when Thomas Breakwell, the first English believer, gave her Count de Gobineau’s stirring description of the Martyrdom of the Bab.

From the beginning of her acceptance of the Faith, Juliet served it. Following her Paris sojourn she spent most of the rest of her life in New York, and her studio there became a center for Bahá’í meetings. Juliet’s great love for and devotion to the Master made her a natural channel for the spreading of the Faith. Her enthusiasm was so soul-warming and contagious that, through her, many people accepted the Cause. She also made it a practice to hold a weekly meeting for the believers.

“Never,” wrote one of her close friends, “will these meetings be forgotten. Those who were fortunate enough to assemble there in those pioneer days were tasting the spiritual happiness they had always read about, which sings on in the heart regardless of the turbulent waters of the outer world. Every evidence of a worldly atmosphere was absent. . .”

The year after the Master’s release from the prison city of ‘Akka, in 1908, Juliet was one of the Kinney party who made the pilgrimage to Haifa. It is not difficult to imagine her exaltation on attaining this longed-for goal.

On her return to New York, her meetings were resumed. Pages of a new volume were being written in the Lives of many devoted American believers; all were looking forward to a possible visit of ‘Abdu’l-Baha to the United States. But in Juliet’s case the interval of waiting seemed to be too long; in the summer of 1911, when the Master was in Europe, she again sought His presence, first at Thonon-les-Bains, France, and then in Vevey on Lake Geneva in Switzerland. Eagerly she listened to His vivifying words, and faithfully she recorded in her diary the priceless impressions of those days.

On April 11, 1912, ‘Abdu’l-Baha arrived in New York, and when He stepped off the steamship Cedric one of those who met Him was Juliet Thompson. She followed the Master everywhere, attending all meetings in New York, Brooklyn and New Jersey and the Master graciously addressed a gathering in her studio. Several times He called her to walk with Him on Riverside Drive, accompanied by Valiyu’llah Vaqa as interpreter. It was through her efforts that the rector of the Church of the Ascension in New York received ‘Abdu’l-Baha at a Sunday evening service, seating the Master in the bishop’s chair beside the altar. Here ‘Abdu’l-Baha answered many questions about the Teachings that were asked by the congregation.

Juliet reached the pinnacle of success and happiness when the Master granted her request to paint His portrait. This she executed in pastels, unfortunately a somewhat perishable medium. Photographic reproductions of the portrait axe to be found in many Bahá’í homes, but the original has been lost.

Juliet reached the pinnacle of success and happiness when the Master granted her request to paint His portrait. This she executed in pastels, unfortunately a somewhat perishable medium. Photographic reproductions of the portrait axe to be found in many Bahá’í homes, but the original has been lost.

Miss Thompson was by now a well known portrait painter, executing many commissions in New York and Washington. Among these was a portrait of Mrs. Calvin Coolidge.

Juliet kept a complete diary of the tremendous events that transpired during ‘Abdu’l-Baha’s visit in and around New York. Her article, “’Abdu’l-Baha, the Center of the Covenant,” gives examples of the responses of people from all walks of life to the dynamic personality of the Master – responses which in most cases she herself witnessed.

Then came World War I — which the Master had prophesied would occur – when all communication was severed between ‘Abdu’l-Baha in the Holy Land and the friends in the United States. Throughout this time of trial and testing, Juliet did not lose the vision of the Bahá’í promise of peace. In collaboration with her spiritual mother, May Maxwell, she collected the utterances of Bahá’u’lláh and ‘Abdu’l-Baha on this subject. These were published in 1918 under the title, “Peace Compilation.

Because of her ardent advocacy of peace, Juliet attracted the attention of federal agents, some of whom were present at Bahá’í meetings in her home. She was never afraid; she knew she spoke the Teachings of God for this day. Throughout her entire Bahá’í career she was courageous, staunch, and firm as a rock in her faith.

Because of her ardent advocacy of peace, Juliet attracted the attention of federal agents, some of whom were present at Bahá’í meetings in her home. She was never afraid; she knew she spoke the Teachings of God for this day. Throughout her entire Bahá’í career she was courageous, staunch, and firm as a rock in her faith.

That Juliet was a sensitive writer was demonstrated in her book, “I, Mary Magdalen,” published in 1940, Here she paints with words a portrait of the woman whose life was deeply influenced by the teachings of Jesus the Christ, just as Juliet’s own life had been galvanized by the radiant loving-kindness and wisdom of ‘Abdu’l-Baha. This book has been characterized as ‘one of the most graphic and lofty delineations of Christ ever made in literature.”

Juliet was for many years a member of the Spiritual Assembly of New York and a delegate to the annual convention. In 1926 she made, with Mary Maxwell, the daughter of her beloved friend and teacher, a second pilgrimage to the Holy Land. After years of service in New York, and not long after Shoghi Eifendi had sent the first

Bahá’í pioneer teachers to Latin American countries, Juliet spent over a year teaching in Mexico.

In the later years of her life, she was incapacitated physically; nevertheless, wherever she was, there was a center around which Bahá’í thought and activity revolved. Doubtless many of her friends did not realize the seriousness of the heart ailment that afflicted her because her spirit was so alive and vibrant. Although she was then in her early eighties, those close to her never thought of age in connection with Juliet; she seemed ageless. Her earthly lift came to an end on December 9th, 1956.

Source:

The Bahá’í World. Kidlington, Oxford: George Ronald Publisher. Volume 1957-1963

-Permission given by George Ronald, Publishers

Images:

Baha’i World Centre Archives

(c) Baha’i Chronicles