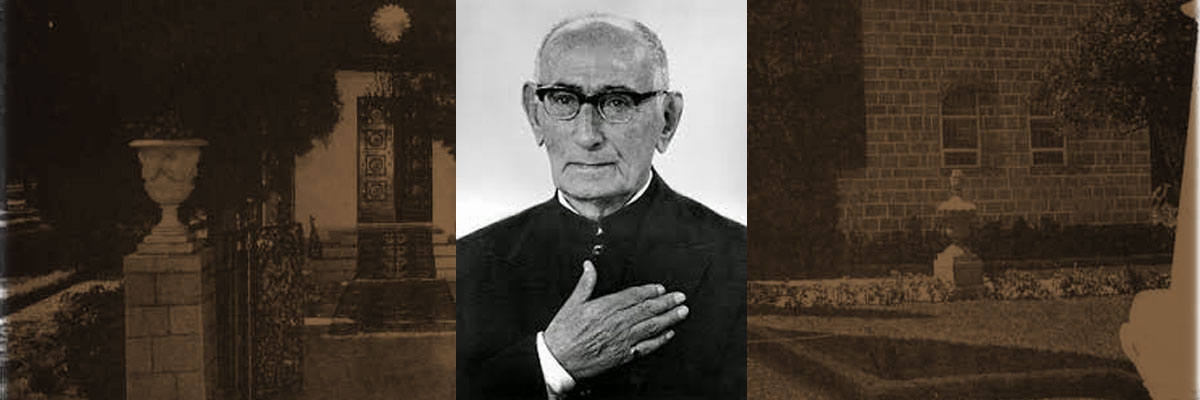

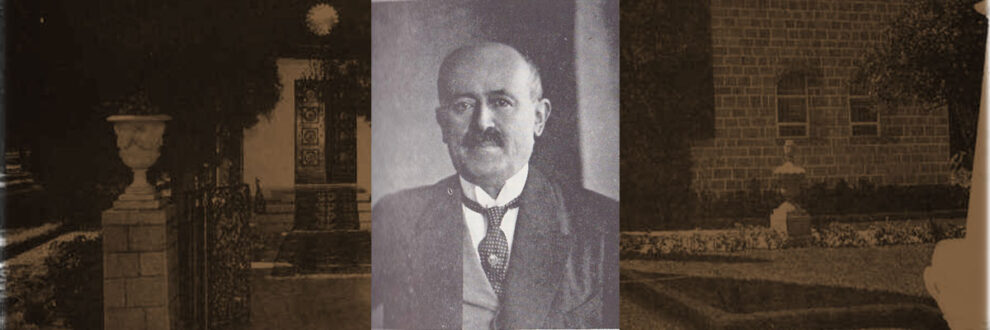

Dr. Youness Khan-i-Afrukhtih (sometimes spelled Yunis) was ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s trusted secretary and interpreter from 1900 – 1909. He went to ‘Akka during 1897 the same year Shoghi Effendi was born.

A being endowed with rare powers and qualities, gifted and uplifted beyond the average level – a real survivor of the Heroic Age. The definition, though brief, may help to convey to the readers’ mind a faint impression of Dr. Youness Afrukhtih’s immortal personality.

By profession Dr. Youness Khan was a physician. He studied medicine at the Presbyterian College, Beirut, and after receiving his diploma he returned to Persia where through efficient and systematic practice, he proved himself a highly proficient physician.

For some time he served as medical officer in the Sehat Hospital founded in 1909 by a group of Bahá’í doctors with the collaboration of Dr. Susan Moody, representing the Persian-American Educational Society. [1]

His Khatirat-i-nuhsali-yi-‘Akka (Memories of Nine Years in ‘Akka) are outstanding. Yunis Khan was a born writer whose art was formed under the influence of the Persian classics. Snatches of Hafiz, echoes of Rumi, add a literary dimension and grace absent from the writings of the others. Yet his style is free of that bane of modern Persian literature — imitativeness. The voice is cultivated but the song is fresh, the language almost colloquial and always vigorous and direct.

In Yunis Khan’s memoirs, as in Mu’ayyad’s, one reads of the coming of pilgrims, among them the distinguished French Orientalist Hippolyte Dreyfus, Lua Getsinger, and Edith Sanderson. Yunis Khan was present when ‘Abdu’l-Bahá resolved a number of problems posed to Him by Laura Clifford Barney. The Master’s casual discourses were later published as Some Answered Questions, a book that has become a basic Bahá’í text.

The effect of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá on the visitors, Yunis Khan writes, was related to their own personalities and the degree of their own spiritual development. The Master was the Sea, and those who immersed themselves received the most. The Sea was never the same. At times it was agitated and full of waves, at other times it was tranquil. True believers did not have to press for answers, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá answered their unasked questions and solved their unstated problems. Finally there were those who had reached the station exemplified by an illumined soul in a story: They asked a gnostic (arif), “What do you desire of God?” He replied, “I desire of God that I might desire nothing.” But whether asked or not, the Master constantly taught the virtues of tolerance, forbearance, and love. The Bahá’ís must not return evil for evil but must shower love on all.

With great evocative power Yunis Khan describes a mournful procession marching to the shrine of Bahá’u’lláh on a November day to commemorate the passing of God’s Messenger. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá walked at the head, followed by the Bahá’ís, each carrying a lighted candle and a vial of rose perfume. At the shrine they sprinkled the perfume among the flowers, set the candles in the ground, and stood still while ‘Abdu’l-Bahá chanted the Tablet of Visitation.

As a medical doctor, Yunis Khan, like Mu’ayyad, records his observations of ‘Abdu’l-Baha’s physical condition. His findings are almost identical with those of Mu’ayyad, who was to examine the Master several years later. Again like Mu’ayyad, Yunis Khan reports that the Master worked long hours, slept little, and ate sparingly (mostly bread, olives, cheese, and seldom meat).

Life at ‘Akka and Haifa in the reign of ‘Abdu’l-Hamid was full of tension and danger. Palestine was a tinder box. Tribes fought each other. Crime was rampant. The streets of ‘Akka were too narrow for bandits to roam free, but in Haifa they were a constant threat. Shots were heard every night but murderers were never apprehended. Whenever ‘Abdu’l-Bahá was in Haifa, the Bahá’ís feared for His life and watched His movements. Frequently He went to visit the poor alone at night, refusing an escort or even a lantern-carrier. However, at a distance a Bahá’í would secretly watch His progress to the very door of His house.

One night it was Yunis Khan’s turn to follow the Master. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá was returning home past midnight when in the dark three shots rang out from a side street. Having become inured to the sound of gunfire, Yunis Khan paid no attention to the first shot. The flash of the second shot sent him running toward the Master. He had reached the intersection, when the third shot was fired and saw two men running away. He was now no more than a step behind the Master. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá walked on without changing His pace or turning His head. His tread was firm and dignified. He had paid no attention to what had occurred but quietly murmured prayers as He walked. At the gate of His house He acknowledged Yunis Khan’s presence, turning to him and bidding him good-bye (“fi amani’llah” – under God’s protection).

One night it was Yunis Khan’s turn to follow the Master. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá was returning home past midnight when in the dark three shots rang out from a side street. Having become inured to the sound of gunfire, Yunis Khan paid no attention to the first shot. The flash of the second shot sent him running toward the Master. He had reached the intersection, when the third shot was fired and saw two men running away. He was now no more than a step behind the Master. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá walked on without changing His pace or turning His head. His tread was firm and dignified. He had paid no attention to what had occurred but quietly murmured prayers as He walked. At the gate of His house He acknowledged Yunis Khan’s presence, turning to him and bidding him good-bye (“fi amani’llah” – under God’s protection).

If ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s life was in danger, so were the lives of uncounted thousands of Bahá’u’lláh’s followers in Persia. In the years after the Persian revolution of 1906 both the Constitutionalists and the reactionaries courted and attacked the Bahá’ís simultaneously. Each realized that the Bahá’ís were potentially a significant force, yet each knew that religious fanaticism could be easily evoked against them. When the Bahá’ís refused to serve either, both groups turned against them. The reactionaries claimed that the Bahá’ís advocated the establishment of a republic. While the constitutionalists accused them of favoring despotism. The massacre of 1903 in Yazd was still fresh in all memories. One can imagine how ‘Abdu’l-Bahá felt, contemplating the possibility of both sides uniting against the Bahá’ís and exterminating the entire community, It was under such circumstances, Yunis Khan reports, that ‘Abdu’l-Bahá insistently urged the Bahá’ís to stay out of politics, abstaining even from opening their lips on subjects that agitated the nation. His position may have been misunderstood by E.G. Browne, who criticized the uninvolvement of the Bahá’ís in Persian politics, but it saved countless lives, and perhaps prolonged the life of the Constitutional movement by dissociating it from the Bahá’í Faith.

“How poor is the world’s workshop of words,” complained a Russian poet. “Where does one find the fitting ones?” Myron Phelps, looking at ‘Abdu’l-Bahá across an ocean which stands for more than geographic distance. Howard Colby Ives, finding personal rebirth in the service of the Servant; Mirza Mahmud-i-Zarqani systematically recording the details of the Master’s journeys; Habib-i-Mu’ayyad and Yunis Khan-i-Afrukhtih, young physicians privileged to listen to His heartbeat — they all tried their best to capture ‘Abdu’l-Bahá for posterity, but He would not be captured. In these profiles, in the long and short accounts, in chronicles and personal memoirs He remains forever the Mystery of God. [2]

Bahá’í poets and people of letters in Persia used to write poems in praise and glorification of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá. But the resident Bahá’ís in Akká were very careful not to breathe a word about His glorious station. They knew He had often advised the poets that instead of singing His praise they ought to exalt His station of servitude and utter self-effacement. One day a laudatory letter arrived addressed to ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, composed in verse. Yunis Khan, who was serving the Master, handed the poem to ‘Abdu’l-Bahá as He was coming down the steps of the house in front of the sea. It appeared the right moment to give it to Him. He had hardly read one or two lines when He suddenly turned His face towards Yunis Khan and with the utmost sadness and a deep sense of grief said:

‘Now even you hand me letters such as this! Don’t you know the measure of pain and sorrow which overtakes Me when I hear people addressing Me with such exalted titles? Even you have not recognized me!… I consider Myself lowlier than each and every one of the loved ones of the Blessed Beauty.’

‘Abdu’l-Bahá spoke angrily in this vein with such vigour that the heart of Yunis Khan almost stopped. His whole body became numb. He wished the earth would open and swallow him up so that he might never again see ‘Abdu’l-Bahá so grief-stricken. Only when the Master resumed His walking down the stairs was he jolted by the sound of His shoes. He quickly followed the Master and heard Him say,

‘I told the Covenant-breakers that the more they hurt Me, the more will the believers exalt My station to the point of exaggeration…’

He was very perturbed that he had brought such grief upon the Master and did not know what to do. Then he heard the Master say,

‘This is in no way the fault of the friends. They say these things because of their steadfastness, their love and devotion…’ Then He said to Yunis Khan, ‘You are very dear to Me…’

Yunis Khan realized that it was always the Master’s way never ever to allow a soul to be hurt. He received comfort and encouragement. His anguish was gone. He was filled with such an indescribable joy and ecstasy that he wished the doors of heaven would open and he could ascend to the Kingdom on high.

(Honnold, Annamarie, Vignettes from the Life of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá) [3]

For years in succession he served with distinction as member of the National Spiritual Assembly of the Bahá’ís of Persia and as member of the Spiritual Assembly of the Bahá’ís of Tehran until he was rather well advanced in age and the weight of years made itself increasingly felt on his frail body. Gradually his health broke down and illness forced him to discontinue all his activities. As his condition grew steadily worse it became clear that his end was at hand. He passed away at his home in Tihran on November 28, 1948 after a prolonged illness. [1]

To read more about Dr. Youness Khan please visit Mr. Thomas Breakwell‘s page here in Bahá’í Chronicles.