Mullá Muhammad-`Alí – Sharifu’l-‘Ulamá entitled Hujjat-i-Zanjáni

Mullá Muhammad-`Alí – Sharifu’l-‘Ulamá entitled Hujjat-i-Zanjáni

Born: 1812-13

Death: January 8, 1851

Place of Birth: Mazindarán, Iran

Location of Death: Fort of ‘Alí-Mardán Khán, Zanján, Iran

Burial Location: No cemetery details (vicinity of Zanján, Iran)

Soon after the Báb, the Herald of the Bahá’í Faith declared His Mission in 1844 some four hundred of the most reputable scholars of Islám in Irán accepted Him as being the Promised Qá’im foretold in the Holy Books.

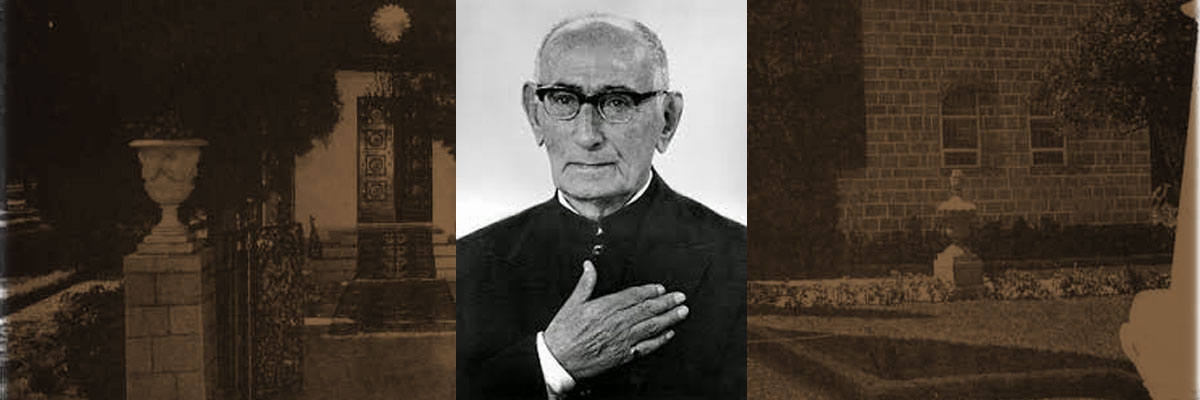

One of the ablest ecclesiastical dignitaries of the age, and certainly one of the most formidable champions of the Bábi Faith was Hujjat-i-Zanjáni, whose name was Mullá Muhammad-`Alí. He was a native of Mazindarán and dignified with the title of Sharifu’l-‘Ulama, Muhammad-`Alí had concentrated his attention on dogmatic theology and jurisprudence, and had become famous. His father, Mullá Rahim-i-Zanjáni, was one of the leading mujtahids of Zanján, and was greatly esteemed for his piety, his learning and force of character. From his very boyhood, he showed such capacity that his father lavished the utmost care upon his education. He sent him to Najaf, where he distinguished himself by his insight, his ability and fiery ardour. The Moslems affirm that, in his function as mujtahid, he showed himself restless and turbulent. Yet many followers considered him a saint, prized his zeal, and put their faith in him.

His father advised him not to return to Zanján, where his enemies were conspiring against him. He accordingly decided to establish his residence in Hamadán, where he married one of his kinswomen, and lived there for about two and a half years, when the news of his father’s death caused him to leave for his native town. From the pulpit of the mosque which his friends erected in his honor, he urged the vast throng that gathered to hear him, to refrain from self-indulgence and to exercise moderation in all their acts. For seventeen years, he pursued his meritorious labors and succeeded in purging the minds and hearts of his fellow-townsmen from whatever seemed contrary to the spirit and teachings of their Faith.

When the Call from Shíráz reached him, he dispatched his trusted messenger, Mullá Iskandar, to enquire into the claims of the new Revelation; and such was his response to that Message that his enemies were stirred to redouble their attacks upon him. Since Hujjat has identified himself with the cause of the Siyyid-i-Báb he won over to that creed two-thirds of the inhabitants of Zanján and the concourse that swarmed his gates, the whole mosque could no longer contain. Such was his influence that the mosque that belonged to his father and the one that has been built in his honor, have been connected and made into one edifice in order to accommodate the ever-increasing multitude that hastened eagerly to follow his lead in prayer.

Following the complaint of the `ulamás, the Sháh decided to summon Hujjat, together with his opponents, to Tihrán. In a special gathering at which he himself, together with Hájí Mírzá Aqásí, the Prime Minister, and the leading officials of the government, as well as a number of the recognized `ulamás of Tihrán, had assembled, he called upon the ecclesiastical leaders of Zanján to vindicate the claims they had advanced. Whatever questions they submitted to Hujjat, regarding the teachings of their Faith, he answered in a manner that could not fail to win the unqualified admiration of his hearers and to establish the sovereign’s confidence in his innocence. The Sháh expressed his entire satisfaction, and amply rewarded Hujjat for the excellent manner in which he had succeeded in refuting the allegations of his enemies.

Upon his return to Zanján while he was addressing the congregation in his mosque, his special envoy whom he had confidentially dispatched to Shíráz with a petition and gifts from him to the Báb, arrived and delivered into his hands, a sealed letter from his Beloved. In the Tablet he received, the Báb conferred upon him one of His own titles, that of Hujjat, and urged him to proclaim from the pulpit, without the least reservation, the fundamental teachings of His Faith. No sooner was he informed of the wishes of his Master that he declared his resolve to devote himself to the immediate enforcement of whatever injunction that Tablet contained.

On a Friday, as soon as Hujjat attempted to lead the congregation in offering the prayer, enjoined upon him by the Báb, the Imám-Jum’ih, who had hitherto performed that duty, vehemently protested. “That right,” Hujjat responded, “has been superseded by the authority with which the Qá’im Himself has invested me. I have been commanded by Him to assume that function publicly, and I cannot allow any person to trespass upon that right.”

His fearless insistence on the duty laid upon him by the Báb caused the `ulamás of Zanján to league themselves with the Imám-Jum’ih and to lay their complaints before Hájí Mírzá Aqásí, pleading that Hujjat had challenged the validity of the recognised institutions and trampled upon their rights. Hájí submitted the matter to Muhammad Sháh, who ordered the transfer of Hujjat from Zanján to the capital.

In the Capital city, several meetings were held between the `ulamás before each of which Hujjat eloquently set forth the basic claims of his Faith and confounded the arguments of those who tried to oppose him.

Hujjat was virtually a prisoner in Tihrán when Muhammad Sháh passed away, leaving the throne to his son Násiri’d-Dín Sháh. The Amír-Nizám, the new Grand Vazír, decided to make Hujjat’s imprisonment more rigorous, and to seek a way of destroying him. On being informed of the imminence of the danger that threatened his life, his captive decided to leave Tihrán in disguise and join his companions, who eagerly awaited his return. His arrival at his native town, was a signal for a tremendous demonstration of devoted loyalty on the part of his many admirers.

More than three thousand men were recruited by the governor from the surrounding villages of Zanján. Meanwhile the companions who observed the growing agitation of their opponents, sought the presence of Hujjat and urged him, as a precautionary measure, to transfer his residence to the fort of `Alí-Mardán Khán, adjacent to the quarter in which he was residing. Hujjat gave his consent and ordered that their women and children, three thousand believers in all, together with such provisions as they might require, be taken to the fort.

Upon receipt of the written orders of the Grand Vazír, Sadru’d-Dawlih, an army commander, marched instantly to Zanján at the head of his two regiments, organized the forces which the governor placed at his disposal, and gave orders for a combined attack upon the fort and its defenders. They attacked the fort from various directions for three days and three nights. The besieged defended themselves under the direction of Hujjat in a remarkable manner. Sadru’d-Dawlih himself had to confess that after the lapse of nine months of sustained fighting, all the men who had originally belonged to his two regiments, no more than thirty crippled soldiers were left to support him.

Though oppressed with hunger and harassed by fierce and sudden onsets, they maintained with unflinching determination the defense of the fort. Sustained by hope that no amount of adversity could dim, they succeeded in erecting no less than twenty-eight barricades, each of which was entrusted to the care of a group of nineteen of their fellow-disciples. At each barricade, nineteen additional companions were stationed as sentinels, whose function it was to watch and report the movements of the enemy. Further evidence of the spirit of sublime renunciation animating those valiant companions was afforded by the behavior of a village maiden, who, of her own accord, threw in her lot with the band of women and children who had joined the defenders of the fort. Her name was Zaynab, her home a tiny hamlet in the near neighborhood of Zanján. For a period of no less than five months, that maiden continued to withstand with unrivalled heroism the forces of the enemy. Finally, beneath a shower of bullets, she dropped dead upon the ground. Not a single voice among her opponents dared question her chastity or ignore the sublimity of her faith and the enduring traits of her character.

The contest was still raging when Hujjat was moved to address his written message to Násiri’d-Dín Sháh. No sooner had the messenger who was carrying those petitions to Tihrán set out on his way than he was seized and brought back into the presence of the governor. Infuriated by the action of his opponents, he ordered the messenger to be immediately put to death. He destroyed the petitions and in their stead wrote the Sháh letters which he loaded with abuse and insult, and, adding the signatures of Hujjat and his chief companions, dispatched them to Tihrán. The Sháh was so indignant after the perusal of these insolent petitions that he gave orders for the immediate dispatch of two regiments equipped with guns and amunitions to Zanján, commanding that not one supporter of Hujjat be allowed to survive.

The news of the Báb’s martyrdom had meanwhile reached the hard-pressed occupants of the fort and spread among the enemy who welcomed it with shouts of wild delight. Seventeen new regiments of cavalry and infantry, including a large number of villagers, had rallied to Amír-Tumán standard, and fought under his command. No less than fourteen guns were, at his orders, directed against the fort. Five additional regiments which the Amír had recruited from the neighborhood, were being trained by him as reinforcements, some thirty thousand men altogether.

The very night he arrived, he issued orders that the trumpets be sounded as a signal to attack. The officers in charge of his artillery were commanded to open fire instantly upon the besieged. The booming of the cannons, which could be heard distinctly at a distance of several miles, had scarcely begun when Hujjat ordered his companions to make use of the two guns they themselves had constructed. One of them was transported to a high position commanding the Amír’s headquarters. A ball struck his tent and mortally wounded his steed. The enemy was meanwhile directing, with unrelenting fury, its fire upon the fort, and had succeeded in killing a large number of its occupants.

As the days of the siege were drawing to a close, Hujjat urged all those who were engaged to celebrate their nuptials. During more than three months these festivities continued, festivities which were intermingled with the terrors and hardships of a long-protracted siege. No less than two hundred youth were joined in wedlock during those tumultuous days. No one among them failed, as the beating of the drum announced the hour of his departure, to respond joyously to the call.

At last, the Amir drew up a treacherous appeal, in which he assured Hujjat of the sincerity of his intention of achieving a lasting settlement between him and his supporters. He accompanied that declaration with a sealed copy of the Qur’án, as a testimony of the sacredness of his pledge.

Hujjat reverently received the Qur’án from the hand of the messenger, and, as soon as he had read the appeal, bade its bearer to inform his master that he would send an answer in the course of the following day.

That night he gathered together his chief companions and spoke to them of the misgivings he entertained as to the sincerity of the enemy’s declarations. The next day Hujjat sent a delegation of nine adolescents and a number of elderly to the enemy’s camp as a gesture of good will and to negotiate the terms of the settlement. They were all captured, some were mutilated on the spot and a few of the children were able to escape and return to the fort.

Seating himself in the centre of the Fort, Hujjat summoned his followers. On their arrival, he arose and, standing erect in their midst he told them that they were free to leave the fort and it was better that his death should appease the enemy’s thirst for revenge rather than that they should all perish.

The companions were moved to their very depths and, with tears in their eyes, declared their firm resolve to remain, to the end, by his side. Following that treachery, the Amír-Tumán ordered no less than sixteen regiments, each equipped with ten guns, to march against the fort. One day, while the bombardment was still in progress, a bullet struck Hujjat in the right arm, as he was performing his ablutions. Though he ordered his servant not to inform his wife of the wound he had received, yet such was the man’s grief that he was powerless to conceal his emotion. His tears betrayed his distress, and no sooner had his wife learned of the injury inflicted on her husband than she ran in distress and found him absorbed in prayer. Though bleeding profusely from his wound, his face retained its expression of undisturbed confidence.

As time went on, their numbers diminished, their sufferings multiplied, and the area within which they could feel secure was reduced. A cannon-ball struck the room which the wife of Hujjat, Khadíjih, occupied. She was holding Hádí, their baby, in her arms when she was killed instantly. Her child, whom she was holding to her breast, fell into the brazier beside her, and shortly afterwards died of the injuries.

On the morning of January 8, 1851 Hujjat, who had already, for nineteen days, endured the severe pain caused by his wound, was in the act of prayer and had fallen prostrate upon his face, invoking the name of the Báb, when he suddenly passed away.

His sudden death came as a severe shock to his kindred and companions. Their grief at the passing of so able, so accomplished, and so inspiring a leader, was profound; the loss was irreparable. Two of his companions, Din-Muhammad-Vazir and Mír Riday-i-Sardar, straightway undertook, ere the enemy was made aware of his death, to inter his remains in a place which neither his kindred nor his friends could suspect. At midnight, the body was borne to a room that belonged to Din-Muhammad-Vazir, where he was buried. They demolished that room in order to ensure the safety of the remains from desecration, and exercised the utmost care to maintain the secrecy of the spot.

Immediately after the death of Hujjat, more than five hundred women and tow hundred men gathered together in his house. His companions, in spite of the death of their leader, continued to face, with undiminished zeal, the forces of their assailants. No sooner had the persecutors finished their work to destroy the fort than they began to look for Hujjat’s body, the place of whose burial the companions had carefully concealed. The most inhuman tortures had proved powerless to induce them to disclose the identity of that spot. The governor, exasperated by the failure of his search, asked that the seven-year-old son of Hujjat, whose name was Husayn, be brought to him that he might attempt to induce him to disclose the secret.

No sooner had the body of Hujjat, been delivered into the hands of the governor than he ordered that it be dragged with a rope, to the sound of drums and trumpets, through the streets of Zanján. For three days and three nights, unspeakable injuries were heaped upon the body, which lay exposed to the eyes of the people in the town square. On the third night, it was reported that a number of horsemen had succeeded in carrying away the remnants of the corpse to a place of safety in the direction of Qazvín. As to Hujjat’s kinsmen, orders were received from Tihrán to conduct them to Shíráz and to deliver them into the hands of the governor. There they languished in poverty and misery. Whatever possessions still remained to them the governor seized for himself, and condemned the victims of his rapacity to seek shelter in a ruined and dilapidated house. Hujjat’s youngest son, Mihdí, died of the privations he and his family were made to suffer, and was buried in the very midst of the ruins that had served as his shelter.

Source:

1-Personal research notes for Bahá’í Encyclopedia (unpublished)

2-De Gobineau, Comte Joseph Arthur. “Religions et philosophies dans l’Asie Centrale”, Paris : Didier & Cie, 1865 pp. 197-198, 200, 202

3-A. L. M. Nicolas’ “Siyyid `Alí-Muhammad dit le Báb,” p. 342

4-Nabil Narrative, The Zanján Upheaval – New York, Bahá’í Pub. Committee, 1932

5-Mirza Husayn Hamadani, “Tarikh-i Jadid.” London. British Library. Oriental and India Office Collections. pp. 138-43.

6-E. G. Browne’s “A Year amongst the Persians,” p. 74.

7-E. G. Browne, “Personal Reminiscences of the Babi Insurrection at Zanjan in 1850,” Journal Royal Asiatic Society, 19 (1897)

8-Hidayat “Rawdat al-safa-yi Nasiri” London. British Library. Oriental and India Office Collections

9-Sipihr “Nasikh al-tawarikh” 1801/2-1879/80 AD, volume III

Images:

Profile image courtesy of Joe Paczkowski

Black and white images were taken by late Muhammad Labib printed in Dawn-Breakers (see the article about the photographer here)

Add Comment