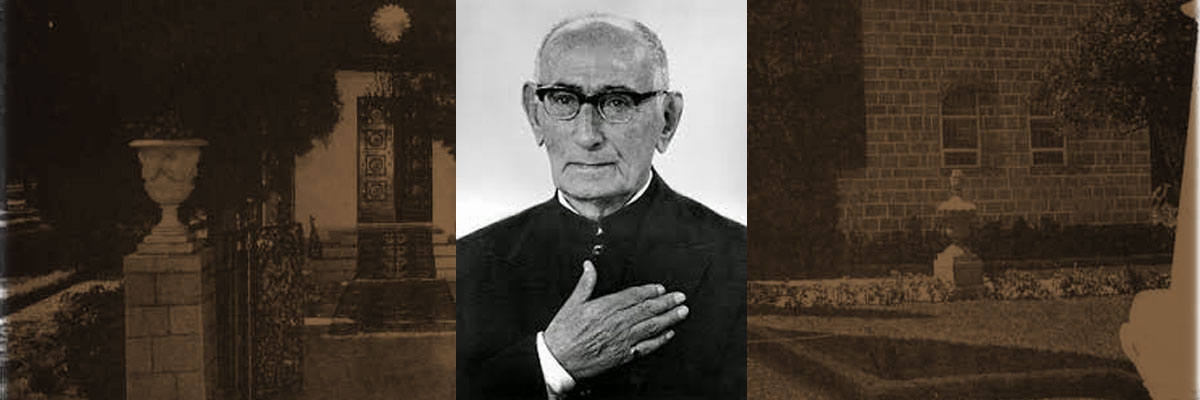

George Jacob Augur

George Jacob Augur

Born: October 1, 1853

Death: September 13, 1927

Place of Birth: West Haven, Connecticut

Location of Death: Honolulu, Hawai’i

Burial Location: O’ahu Cemetery, Honolulu, Hawai’i (Oahu Cemetery at 2162 Nuuanu Street in Honolulu. Markers for his wife, Ruth (d. 1938); his son, Morris (d. 1938); and his son’s first wife, Myrtle (d. 1936), and second wife, Eleanor (d. 1997), are adjacent to his)

American doctor who became one of the early Bahá’ís of Hawai’i and was the first resident Bahá’í in Japan, living there for significant periods from 1914 to 1919; designated by Shoghi Effendi a Disciple of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá.

George Jacob Augur was born on October 1, 1853 in West Haven, Connecticut, the second of eight children of Abraham Augur, a farmer, and his wife, Ellen (née Morris). After graduating from Hopkins Grammar School and Yale Preparatory School, George Augur entered Yale University Medical College in 1876, graduating in 1879. He was resident physician and surgeon at the State Hospital in New Haven (now Yale–New Haven Hospital) between 1879 and 1882. He attended the Fair Haven Congregational Church, where he served as superintendent.

In 1882, Augur moved to Oakland, California. There he opened an office in downtown Oakland and also served for some fifteen years as an attending physician on the staff of the East Bay’s first hospital, the Oakland Homeopathic Hospital and Dispensary, renamed the Fabiola Hospital in 1887. Organized and managed by women and including women physicians on its staff, from 1877 until 1932 the hospital provided both conventional (allopathic) and homeopathic treatments, particularly for the indigent and the working poor. Augur worked as an allopathic physician until 1895, when he became a practitioner of homeopathy—an “‘apostasy,'” as it was later described, that “cost him in preferment and friends.”

On June 16, 1892 in Oakland, Augur married Ruth Barstow Dyer, a native Californian (January 16, 1864). Their union produced one child, Morris Curtis Augur, born on March 1, 1894.

Finding that the climate of the Bay Area did not suit him, George Augur moved to Honolulu, Hawaii, arriving aboard the SS Australia on February 1, 1898. He opened a medical practice and was soon joined by his wife and son.

In the winter of 1905, Ruth Augur’s sister Alice Otis—who resided in Honolulu with her husband, a former sea captain—became a Bahá’í and opened her home for Bahá’í meetings. The sisters had connections with Bahá’ís not only in Honolulu but in Oakland; their family home was a few doors away from the Jackson Street residence of Helen Goodall, one of the early Bahá’ís of the Bay Area, and members of the two families moved in the same social circle. Ruth Augur, although content in her Christian faith, began attending the meetings and in 1907, when her sister was going away, invited the Bahá’ís to meet in her home on Beretania Street. “From that time in 1907,” Agnes Alexander—the first Bahá’í of Hawai’i and a colleague of Augur’s in both Honolulu and Japan—recalls, “the Augur home became the radiant center of the Cause in Honolulu where the weekly meetings were held and the Baha’i library kept. Except during the intervals when the Augurs were away from the Island, for many years the Baha’is met there.”

Sometime between 1907 and 1909, both Ruth and George Augur became Bahá’ís, further enhancing “a spiritual bond” between the Bahá’ís of Oakland and Honolulu. In 1911, George Augur was appointed the first treasurer of Hawai’i’s Bahá’í group.

Edward S. Goodhue, a noted allopathic physician and author in Hawai’i who interviewed Augur shortly before his death, found much to admire in Augur: “A typical New Englander to his 74th year—erect in carriage as in character, a fine, fragile piece of humanity out of the Puritan block. Careful in his mode of dress, in his language, his habits and friendships, fastidious as to order and routine of duty, he was a loyal, true friend to those he accepted as such.” Goodhue, though he approached the practice of medicine from a differing perspective, commented on Augur’s “firmness and loyalty to sincere conviction” and on the way in which Augur explained having become a homeopath—”very gently, and characteristically regardful of the feelings and perhaps prejudices of one belonging to a different school.”

For Alexander, Augur was “independent in his convictions and accustomed to standing alone.” Whereas Ruth Augur “had a mother heart of love which she showered on everyone,” George Augur had a quiet and reserved disposition: “He was a man of few words, but his love for ‘Abdu’l-Bahá and insight into His station [at a time when many in the West thought of Him as a prophet or even the return of Christ] gave power to his words.”

Augur received six letters from ‘Abdu’l-Bahá. The first, dated early in 1909, addressed Augur’s request for an explanation of Hebrews 4:15: “For we have not an high priest [Jesus, the Son of God] which cannot be touched with the feeling of our infirmities; but was in all points tempted like as we are, yet without sin.” The second, written in 1913, clarified Augur’s understanding of the stations of Bahá’u’lláh and ‘Abdu’l-Bahá. Later letters focused on Augur’s services in Japan.

George Augur’s attraction to that country dated back to a three-month-long holiday there in 1906. “Refined in his taste, he had great appreciation of Japan,” Agnes Alexander relates. “The small garden at the back of his home in Honolulu, he had designed in the form of a Japanese garden.” In 1913 Augur wrote ‘Abdu’l-Bahá of his desire to go to Japan for an “indefinite stay.” In November of that year, Augur received a response: “Arise thou to perform the blessed intention thou art holding and travel thou to Japan and lay there the foundation of the Cause of God, that is, summon the people to the Kingdom of God.”

Traveling alone, Augur left for Japan in May 1914. On his arrival in Tokyo in June, he became the first Bahá’í to take up residence in that country. He began making friends and studying the language. Soon he received a tablet from ‘Abdu’l-Bahá that said in part, “A thousand times bravo to thy magnanimity and exalted aim!” On November 6, 1914 Augur met Alexander at Tokyo Station. Having arrived at Kobe on November 1, 1914, she became the second resident Bahá’í in Japan.

Alexander records that in April 1915 Augur went to Hawaii to rejoin his wife, “expecting to come back to Japan with her in the fall” but perhaps not having fully decided. He wrote ‘Abdu’l-Bahá about his plans but carried out the decision before receiving a reply. “Dr. Augur felt very strongly the call to return to Japan,” Alexander remembers, “and dear Mrs. Augur would not put anything in his way and came with him.” Shortly after the Augurs arrived in Tokyo, Alexander wrote a letter dated October 28, 1915 in which she describes how Augur reached the decision to return:

Dr. Augur has told me that before their coming, in Honolulu a dear friend of theirs was trying to persuade him that it was a mistake for him to think of returning to Japan at this time. He took up the Hidden Words and opened them in order to get light, and these were the words which came before his eyes: OH MY SERVANT! Free thyself from the worldly bond, and escape from the prison of self. Appreciate the value of time for thou shalt never see it again, nor shalt thou find a like opportunity. These words left no doubt in Dr. Augur’s mind about coming.

‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s response, dated August 8, 1915, had to be forwarded from Honolulu to Tokyo. “Your beautiful petition … was read this morning to the Beloved of our hearts,” ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s secretary replied. “His face beamed with heavenly smile as he heard your name. . . . He said: ‘Write to Dr. Augur to return to Japan as soon as the first opportunity offers itself to him. Great blessings will descend upon the soul who teaches the Cause in that country. Its people are endowed with great capability.'”

At first the couple lived in a Japanese inn in Tokyo—an arrangement Augur found comfortable. According to Agnes Alexander, “He was fond of Japan, and its food and dress appealed to him.” Although Ruth Augur used some furniture she had brought from Honolulu, “Dr. Augur kept his room in the Japanese style, using a cushion to sit on the matted floor.”

Early in 1916, the Augurs moved from Tokyo to a rented Japanese-style house in Zushi, a town on the seashore south of Tokyo, where they lived for nearly two years. George Augur returned to Tokyo each Friday to support the weekly meeting he and Alexander had inaugurated immediately after her arrival in November 1914. She found him “a great help” because of his knowledge of the Bahá’í teachings. “In answer to almost any question, he can quote the exact words of ‘Abdu’l-Baha or Baha’u’llah.” In 1916 Dr. Augur wrote a magazine article titled “What is Bahá’ísm”; published separately as a booklet, it became one of the first Bahá’í publications in Japanese.

The Augurs left Zushi for Honolulu in December 1917, but went back to Japan for a final sojourn. From the fall of 1918 until the spring of 1919, Alexander records, “They rented a little furnished Japanese house in Tokyo, where they assisted with the Bahá’í work.”

In 1919, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá gave permission for the couple to return home:

Your services at this spot are recognized and appreciated, particularly (your services) in Tokyo. . . . These few seeds of corn that ye have sown in that soil shall lead to luxuriant crops, this limited number of souls will be converted into great cohorts, nay, rather into an imposing spiritual army, and that seed, under the Divine Direction, shall yield abundant and heavy clusters. . . . If souls should undertake a voyage from America or Honolulu to the land of Japan, the teachings of God shall thereby be swiftly propagated and important consequences shall result. You two have fulfilled your roles and have striven within the limits of your capacity. At present ye must rest for a time; the turn of others has arrived, that they may similarly travel to Japan, may water the seeds that have been sown and may serve and take care of the tender shrubs.

On returning to Honolulu in 1919, Augur resumed his homeopathic practice. The couple continued Bahá’í activities in their large Beretania Street home until 1927, when they moved to an apartment at the beach in Waikiki—”not as beautiful as Zushi,” Alexander recalls Augur having commented. That same year Augur also communicated to Goodhue his continuing attachment to Japan: “There his kindly attitude toward all men and things, as well as his artistic temperament, found a rich field for service. He loved Japan! Like other missionaries who have gone to the wonderful people of Nippon for special propaganda, he found himself a convert to tolerance and a gentle courtesy.”

Augur described his father in a letter to Nancy Bowditch written February 24, 1938: My father was about 5 feet 8 inches in height and weighed about 140; as a matter of fact his weight varied very little during the past thirty years of his life. He had dark, curly hair and eyes of a deep blue, as some one once described them, ‘eyes that were the color of the sky’. His skin was fair. He was extremely neat in appearance.

George Jacob Augur died of a stroke on September 13, 1927 in Honolulu.

Keith Ransom-Kehler, whose world travels included Japan, paid tribute to him with these words: “The names of Dr. Augur and of Agnes Alexander must ever remain the names to which all others are subsidiary in recounting the history of the Cause in Japan.” Another contemporary, Helen Bishop, said of Augur: “This immortal pioneer adopted the Japanese psyche: that is to say, he spoke the language, lived in a Japanese house, wore the formal kimono, and chose the serene canon of taste which consists in putting away all treasures saving but one point of contemplation—such as a rose, a vase, book or bibelot.”

A letter written on behalf of Shoghi Effendi states: “He was deeply grieved to hear of the death of Dr. Augur. He prays that in seeking eternal rest, his soul may soar to heavenly kingdoms and attain an everlasting bounty. Surely he is now where he would much love to be. Please convey to his family Shoghi Effendi’s deepest sympathy and regret.”

In volumes of the Bahá’í World published in 1930 and 1933, a list prepared by Shoghi Effendi designates nineteen Western Bahá’ís as “The Disciples of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá: ‘Heralds of the Covenant.'” Their photographs appear with accompanying identifications. In both volumes Augur is number nineteen, described as “Dr. J. G. Augur: pioneer of the Faith in the Pacific islands.”

Source:

Troxel, Duane K. “Augur, George Jacob” Bahá’í Encyclopedia Project, bahai-encyclopedia-project.org

Images:

Baha’i World Centre Archives