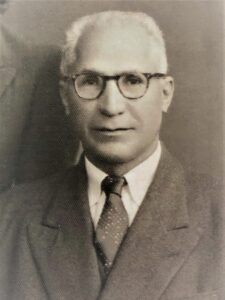

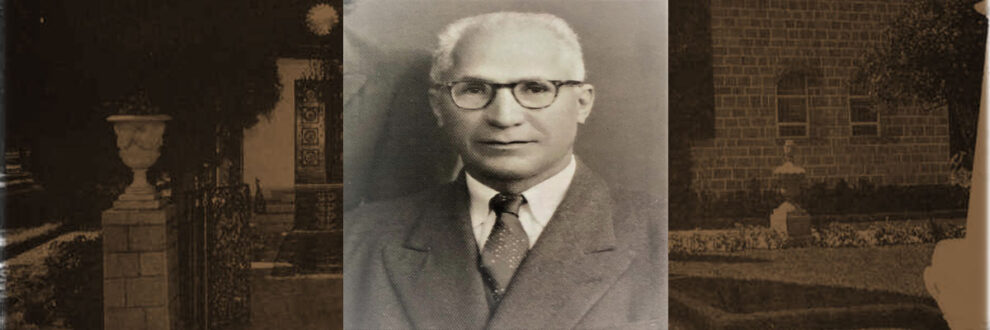

Abbas Behroozi

Born: 1898

Death: April 15, 1987

Place of Birth: Hamadan, Iran

Location of Death: Lyon, France

Burial Location: Lyon, France

Abbas Behroozi was born in 1898 in Hamadan. His mother died during childbirth and left him and his nine brothers and sisters as orphans. My father left home when he was a teenager. He first went to Turkey then Iraq and learned conversational Turkish and Arabic when communicating with the public. While in Baghdad, he joined the Military Medical Corps, studied medicine and was certified as a medical doctor. Then he was stationed at the Royal Hospital outside Baghdad.

My father was not aware that the Royal Hospital was situated at the old Najibiyyih Garden. One day while taking a break in the hospital garden, he saw an old man outside the gate, waving and beckoning him. My father asked the guard to let him in. The old man told my father that he had been watching my father for a while and thought it was important to let him know that a significant event had taken place in this Garden. He had urged my father to find out more about this by contacting the Bahá’ís. He left, and my father never saw him again. Some time passed before my father crossed the path of the Bahá’ís and was introduced to Mr. Abbas Alavi, a great Bahá’í teacher, and scholar. Through Mr. Alavi’s loving instruction my father learned about the Bahá’í Faith. He believed that he was destined to work in the “Garden of Ridvan,” where Bahá’u’lláh declared his mission to his followers; the great event that the old man urged the young doctor to investigate. My father was attracted to Faith’s progressive teachings, such as the equality of women and men, and a Faith which was devoid of the religious prejudices and fanaticism of Muslims. As he loved Zoroaster, the ancient Iranian Messenger of God, he admired the Persian lineage of the Báb and Bahá’u’lláh .

In 1926, when my father visited his aunt in Tehran, he met my mother and married her in the Muslim tradition. It took years for my mother to overcome her strong prejudice and gradually, through the patient mentoring of Mr. Alavi, she first accepted the Báb, and later Baha’u’llah. They had their two sons when in 1935, my father gained employment with the Anglo-Iranian Oil company, and the family moved to Abadan. My father by that time could speak English and a bit of French. He told me that he used to memorize 100 words from the English dictionary each day, to learn the language and get employment with the Oil Company.

After the WWII, my family settled in Tehran. In 1960’s my father became a member of the National Teaching Committee of Iran and visited a wide range of the Bahá’í Communities in Iran. My father’s mission was to help each locality to develop their own teaching and consolidation plan. He made these visits a family affair, and we accompanied him on most of these trips.

The first community in my father’s schedule was in the Mazandaran Province. Some of the survivors of Fort Tabarsi decided to settle down in a few Mazandaran villages and asked their families to join them. The result of this movement was a number of “all Bahá’í” villages in this region. We visited one of these in Mazandaran. It was in a lush forest. A single log bridge over a river was the only access to the village.

The residents were proud that Abdu’l‑Baha, in one of his tablets called their village the “Lush Paradise.” This village was a glimpse of what Abdu’l-Baha described as the future Bahá’í villages in the years to come. The village was divided into a Bahá’í and a Muslim section. By entering the Bahá’í section, one immediately noticed the care shown for the cleanliness and beautification by its dwellers.

Our next destination gave us a chance to visit the Shrine of Quddus. The deceptive capture of the surviving heroes of Tabarsi by the Prince, who betrayed his promise of safe passage if they surrendered, led to the martyrdom of Quddus. After his arrest, he was taken to the city, tortured, and eventually, his precious body was put on fire. It took a great undertaking to salvage the remains of Quddus and secretly bury him in a simple and ordinary residential home. No tombstone or marking was permitted, in order to protect his remains and to prevent further desecration of his burial place. These precautionary measures limited the believers from visiting most of the Holy Spots in Iran without special permission of the National Spiritual Assembly. As too much traffic would attract the enemies of the Faith and make their safekeeping at risk. Unfortunately, most of these Holy Places have been destroyed following the Iranian Revolution. It saddens my heart that future generation of Bahá’ís will not be able to have the soul cleansing experience of visiting these sacred spots which were the testaments of the sacrifice and the greatness of the heroes of our Faith. In our journey to Zanjan, we paid homage to the ruins of its Fortress, where Hujjat Zanjani, the great scholar of the Heroic Age and his entire entourage gave their lives as a testament of their love for their Beloved.

The next leg of my fathers’ trip was to the Azerbaijan province. The land of imprisonment and martyrdom of His Holiness the Báb. We entered “Arq Citadel,” an imposing and gloomy structure, where his Holiness the Báb spent the last days of his life. Arq Citadel had been preserved as a National Monument by the Government of Iran for its historical value, entirely unrelated to its significance to the Bahá’ís . There was only a part of the original structure remained. We then visited the Sacred Spot where his Holiness the Báb faced the firing squad. We had to be extremely careful to keep the appearance of being a sightseer when our heart was crying out to chant the Tablet of Visitation and tears were welling up in our eyes. We then visited the site which replaced the old moat; where after the execution, the soldiers disposed of the sacred remains of the Báb and his young companion Anis.

We imagined Solayman Kahn’s stellar bravery in secretly carrying his Beloved’s remains out of Tabriz into a private residence in a remote village of Azerbaijan. We were privileged to visit this well-hidden and historically significant house. The villagers were quite hostile toward the Faith. The caretakers of this home, who were the only Bahá’í family there, were quite isolated from the village community life. No one sold any goods to them or bought their products. The house was spotlessly clean. I entered the basement, a private Persian bath where the sacred remains were cleansed, according to the Bábi burial laws and kept for a length of time. Every atom of this place was charged with such spiritual power, penetrating every cell of my body. It was a spiritual baptism of my soul. We left this sacred house and its residents with heavy hearts and a renewed sense of faith. We hoped that as their only Bahá’í visitors for quite some time, we had given them some emotional support to continue with their sacrificial service.

My father started a Medical Clinic in the southern part of Tehran to help its underprivileged residents. Meanwhile, he joined a core group of medical professionals, organized by Dr. Farhangi, who regularly visited villages which had a Bahá’í population. They offered free medical services to the Bahá’í and non-Bahá’í villagers. My father and other volunteers took their families with them to extend friendship and emotional support. The Bahá’ís in the village made all the necessary arrangements for the day of the visit. They welcomed us with radiant smiles and excellent hospitality.

During the Fasting period of 1968, Dr. Muhajir made a visit to Tehran. I went to see him. As usual, he acted as a long-life friend. He inquired after my pioneering plans. I briefly told him about my parent’s objection and pleaded with him to make a short visit to our house and talk to my parents. The next day I took Dr. Muhajir and his two sisters to my house, which as he told me later, was one of the most challenging encounters of his life. The conversation was short and abrupt. My mother did not want her young daughter to go to a strange island, but she would let me leave when I got married. Dr. Muhajir looked at me and said, Shahla Jan (dear Shahla), if this were a court of law, my verdict would be in your favor. However, as she is your mother, I can’t rule against her. Then he stood up and graciously left the room accompanied by his sisters. My mother was so upset that she did not extend the courtesy of walking them out, but my father did. When we reached the main entrance, Dr. Muhajir held my father in both arms, looked him directly into his eyes and said: “Dr. Behroozi, your daughter has been entrusted to you by God, with the main purpose of serving Him. If you do not fulfill your obligation, you will be answerable to Bahá’u’lláh in the next world!” Then, he said goodbye and left my father pondering about his next move. No immediate change came out of this potent statement.

During the Fasting period of 1968, Dr. Muhajir made a visit to Tehran. I went to see him. As usual, he acted as a long-life friend. He inquired after my pioneering plans. I briefly told him about my parent’s objection and pleaded with him to make a short visit to our house and talk to my parents. The next day I took Dr. Muhajir and his two sisters to my house, which as he told me later, was one of the most challenging encounters of his life. The conversation was short and abrupt. My mother did not want her young daughter to go to a strange island, but she would let me leave when I got married. Dr. Muhajir looked at me and said, Shahla Jan (dear Shahla), if this were a court of law, my verdict would be in your favor. However, as she is your mother, I can’t rule against her. Then he stood up and graciously left the room accompanied by his sisters. My mother was so upset that she did not extend the courtesy of walking them out, but my father did. When we reached the main entrance, Dr. Muhajir held my father in both arms, looked him directly into his eyes and said: “Dr. Behroozi, your daughter has been entrusted to you by God, with the main purpose of serving Him. If you do not fulfill your obligation, you will be answerable to Bahá’u’lláh in the next world!” Then, he said goodbye and left my father pondering about his next move. No immediate change came out of this potent statement.

At that period my father had a severe eye problem, due to glaucoma. He had lost a great deal of his eyesight and needed immediate medical treatment in England. The family encouraged him that since he had to go abroad, it would be good for him to go on Pilgrimage. His request was accepted, and he was set up for his journey. I was aware of the impact of the Pilgrimage on the spiritual transformation of the pilgrim. I prayed for my father, and his change of heart and wrote a letter to Mr. Faizi, imploring him to talk to my father and help him understand the significance of pioneering in my life. I received a letter from him, the day that my father left the Holy Land. Mr. Faizi assured me that not only him, but Mr. Furutan, and members of the Universal House of Justice; Mr. Nakhjavani, and Mr. Fatheazam, all counseled my father and encouraged him to let go of me, and help me achieve my heart’s desire, which in fact should be the highest aspiration of every Bahá’í youth.

When my father came back from his journey, in private, he told me how privileged he felt in having such special treatment from such esteemed personages. He repeated his promise to them that he would let me go as soon as he could convince my mother. He advised me not to mention my intention to anyone for fear of them blocking my departure. He was aware of the consequences of this action and knew that it might cost his marriage. But he believed that what I was doing was right, and as a father, he was ready to go through this suffering to let me serve God. He said, to just remember him while I was doing God’s work, and in this way, he might have a chance to do his share by helping me. It was an incredibly hard and emotional situation. What he had predicted was not half as hard as what happened, but his help also brought about a resounding honor for him that he cherished for the rest of his life, among them, fulfilling the pledge that he had made in the Holy Land.

A Tribute to My Father: In 1979, I went with my family to visit my father, who had remarried and lived in a city by the Caspian Sea. He was a member of the Local Spiritual Assembly, a Homefront pioneer and active in the Bahá’í community. Not long after the revolution, he was diagnosed with cancer and had to return to Tehran for treatment. While he was undergoing chemotherapy, he was arrested, imprisoned and interrogated extensively. As I was his only Bahá’í child, they placed me on their wanted list. Eventually, they confiscated his savings and properties and released him on bail to complete his treatment. When his cancer was in remission, he received a warrant for his arrest. He fled to Pakistan and eventually lived as a refugee in France. Throughout his ordeal, to protect his family, he was incommunicado, and we had no news from him until his death. The Bahá’í community in France contacted my brother and let him know of his passing, who in turn, informed me of the sad news. Decades later, returning from the Holy Land, I visited the lonesome grave of my father in Lyon. I blessed it with the rosewater that I brought from the Holy Shrines and prayed for the progress of his soul.’

Images:

Courtesy of Shahla Gilibanks (daughter of Abbas Behrooz)

Add Comment