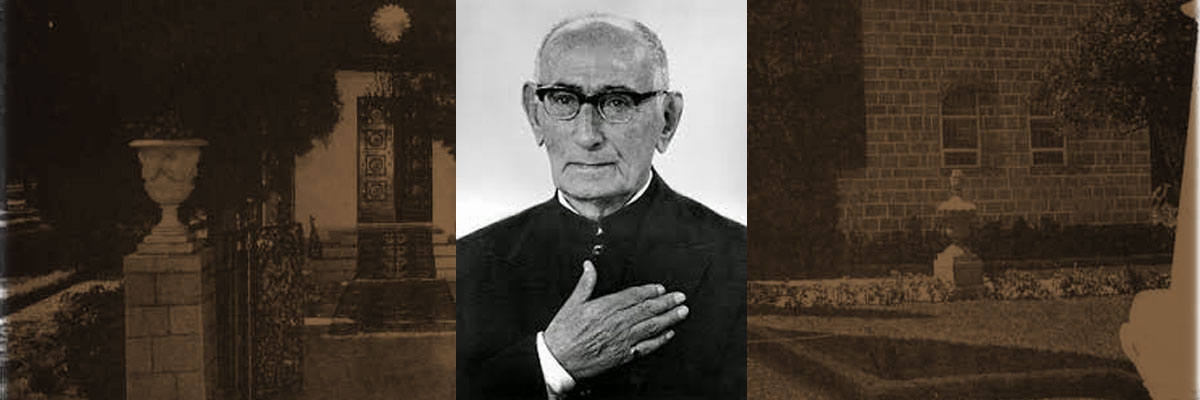

Mirza Ali-Muhammad (Varqa)

Mirza Ali-Muhammad (Varqa)

Born: 1855/1856

Death: May 1, 1896

Place of Birth: Yazd, Iran

Location of Death: Tehran, Iran

Burial Location: No cemetery details

Ruhu’llah Varqa

Born: 1884

Death: May 1, 1896

Place of Birth: Tabriz, Iran

Location of Death: Tehran, Iran

Burial Location: No cemetery details

Editor’s Note:

It was important to list the source here at the top as this is a transcript from an audio-cassette from Dr. Darius K. Shahrokh “Windows To The Past”.

Mirza ‘Ali Muhammad Varqa – Varqa means ‘Dove’. He was a prominent lranian Bahá’í renowned as a poet. He and his young son, Ruhu’llah, were killed by one of the Qajar courtiers in the aftermath of the assassination of NASIR’D-DIN SHAH. ‘Abdu’l-Baha named him posthumously as a HAND OF THE CAUSE, and Shoghi Effendi designated him as one of the APOSTLES Of BAHA’U’LLAH.

With the one-hundred-year anniversary of the martyrdom of Varqa and his son, Ruhu’llah, at hand, this presentation is only a humble tribute to their memory.

This window will not open just to the life-story of two shining stars of the Faith. It will recount one hundred-fifty years of the history of the illustrious family of Varqa. This family not only offered two martyrs at the threshold of the Blessed Beauty, but also has the unique distinction of being the only family with the grandfather, father, and son successively honored with the title of Hand of the Case.

With that in mind, let this window from these ageless windows to the past open to the endless horizon of selfless dedication and infinite skies of service and sacrifice. Let us sit back and open the window wide so nothing will be missed. Just look at them. How free and happy they look. Can’t you see them? Well, friends, this is the window of imagination which brings the past to life. After all, that past some day was someone’s future, and your and my present and future will become someone else’s past. Just an illusion. Now that you are with me, we can all watch it together. Of all the wonders spread before us, two heavenly doves catch our eyes.

With that in mind, let this window from these ageless windows to the past open to the endless horizon of selfless dedication and infinite skies of service and sacrifice. Let us sit back and open the window wide so nothing will be missed. Just look at them. How free and happy they look. Can’t you see them? Well, friends, this is the window of imagination which brings the past to life. After all, that past some day was someone’s future, and your and my present and future will become someone else’s past. Just an illusion. Now that you are with me, we can all watch it together. Of all the wonders spread before us, two heavenly doves catch our eyes.

We will follow their mesmerizing flight through this illusive mortal world, and see how they weathered successive turbulences, each one lifting them higher, until they soared towards the apex, disappearing into that timeless and spaceless world.

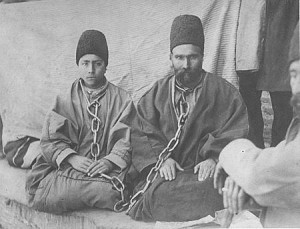

The father was Mirza Ali-Muhammad Varqa, whose fluent pen gave him the surname of silver-tongued nightingale. The title of Varqa, meaning “Dove,” was conferred upon him by Bahá’u’lláh. In the course of this story, we shall refer to him as Varqa. The title of Hand of the Cause was conferred posthumously by ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, and Shoghi Effendi designated him as one of the nineteen Apostles of Bahá’u’lláh. His son, Ruhu’llah, at his tender age was called by Bahá’u’lláh ‘Jinab-i-Mobbaligh,’ (meaning the honorable Bahá’í teacher). Ruhu’llah, meaning the Spirit of God, is one of the titles of Christ. Their photograph was taken while under chain in the prison during their last days has adorned the cover of this tape.

How did it all begin? We turn the pages of history back to the first couple years of this Dispensation. What you are going to hear is extracted from six books, four in English, which are Memorials of the Faithful by ‘Abdu’l-Bahá; God Passes By by Shoghi Effendi; Eminent Bahá’ís in the Time of Bahá’u’lláh by Hand of the Cause H. M. Balyuzi; and The Revelation of Bahá’u’lláh, Volume IV by Mr. Adib Taherzadeh. Two in Persian are Masabih-i-Hidayat, Volume I by Azizu’llah-i-Sulaymani; and Khushih-Ha-i Az Kharman- i-Adab va Hunar, Volume V published by Landegg Academy in Switzerland.

The early believers whose names you will hear are among the spiritual giants who were so magnetized by the love of Bahá’u’lláh that the Guardian states, “…the like of whom will not rise again.” Martha Root, in the West, called the foremost Hand of the Cause by the Guardian, was in that category.

In that Holy Year of 1844, a spark was ignited by the Báb in Shiraz, the flame of which soon engulfed the whole country of Persia, now called Iran. The first city which became ablaze was Shiraz. The second year after the Declaration of the Báb, the king both alarmed and interested, sent his most learned and trusted man, Siyyid Yahya Darabi, later to be known as Vahid, to Shiraz to investigate the Cause of the Báb. Vahid, on his way, stopped in another southern city called Yazd, and in a large square proclaimed the nature of his assignment by the king.

In that Holy Year of 1844, a spark was ignited by the Báb in Shiraz, the flame of which soon engulfed the whole country of Persia, now called Iran. The first city which became ablaze was Shiraz. The second year after the Declaration of the Báb, the king both alarmed and interested, sent his most learned and trusted man, Siyyid Yahya Darabi, later to be known as Vahid, to Shiraz to investigate the Cause of the Báb. Vahid, on his way, stopped in another southern city called Yazd, and in a large square proclaimed the nature of his assignment by the king.

Then occurred one of the greatest and most exciting events in the history of the Faith which amazes the mind. An encounter between worldly knowledge and a Manifestation of God. Learn about it by studying the history of the Báb. In the third and last interview, Vahid was struck dumb, and his purpose to defeat the Báb in argument was changed into unshakeable belief in the Báb. Vahid wrote to the king about the outcome.

After leaving Shiraz, he went through the city of Yazd again, and in the same square, he declared his newly-found Faith to the anxious and curious crowd. Many became believers on the spot. One of them was Haji Mulla Mihdi-i-‘Atri, the father of Varqa. He was known for his expertise in making rose-water and attar of rose, and thus comes the last name, Atri, meaning the perfume-maker.

He invited all Babi traveling teachers to teach his wife, who also became a Babi. He had three sons, Mirza Husayn, Mirza Hasan, and Mirza Ali-Muhammad, and one daughter, Bibi Tuba. [The prefix of Mirza for these sons signifies that through their mother they were descendants of Fatimih, the daughter of Muhammad] [If the blood relationship is through the father, like in the case of the Báb, the prefix is Siyyid]

Mulla Mihdi became a very active teacher. After one of his teaching trips, he arranged a large gathering of the believers, nearly two hundred, in his house for devotions. This was a bold move compared to the usual secret meetings of small numbers. One of the guests who had a very beautiful voice chanted a few times in that gathering.

Of course, as expected in that fanatic city and elsewhere, this resulted in Mulla being summoned the next day to the house of the chief clergyman. After punishment by bastinado (whipping of the soles of the feet), he was expelled from the city. Apparently, a number of the evil clergy had signed his death sentence, but one fair-minded and influential clergyman intervened. The day Mulla was arrested, the oldest and the youngest sons went into hiding, and the other son left the city. This was around 1877.

Mulla Mihdi took his oldest son, Husayn, and the youngest, Varqa, twenty-two years old, and turned their backs to the city of their birth, and took the road on foot. From the southern city of Yazd, they directed their steps towards Akka. On their way, they reached the distant city of Tabriz in the northwest where less than three decades earlier the Bab had been martyred. There they were the guests of the Ahmad family.

Let us direct our attention to the developments in Tabriz which would become their new home-town. The city of Tabriz was the domain for the crown princes in the Qajar dynasty. In that period, the king was Nasiri’d-Din Shah, and the crown prince was Muzaffarid- DinMirza. (Mirza at the end of a name means a prince.) The chief attendant of this prince was a Bahá’í from Nur. Nur was also Bahá’u’lláh’s ancestral home. His name was Mirza Abdu’llah Khan- i-Nuri. We shall refer to him as Mirza. Mirza soon became acquainted with Varqa, and was highly impressed by his charm and knowledge. Varqa was learned about literature, well-versed about holy writings of the past and the Faith. He know the science of ancient medicine, and was an outstanding poet.

Let us direct our attention to the developments in Tabriz which would become their new home-town. The city of Tabriz was the domain for the crown princes in the Qajar dynasty. In that period, the king was Nasiri’d-Din Shah, and the crown prince was Muzaffarid- DinMirza. (Mirza at the end of a name means a prince.) The chief attendant of this prince was a Bahá’í from Nur. Nur was also Bahá’u’lláh’s ancestral home. His name was Mirza Abdu’llah Khan- i-Nuri. We shall refer to him as Mirza. Mirza soon became acquainted with Varqa, and was highly impressed by his charm and knowledge. Varqa was learned about literature, well-versed about holy writings of the past and the Faith. He know the science of ancient medicine, and was an outstanding poet.

Well, Mirza had a wife who was from a high class family from the Shahsavan tribe. She strongly opposed the Faith and bitterly hated the Bahá’ís. They had a grown daughter, but the wife could not bear another child. Mirza, badly wishing to have the company of Varqa, told his wife that there are these new people passing through the city, one of whom has the knowledge of medicine. Maybe they could be invited for supper so Varqa could prescribe some remedy to cure her. Desperately wanting another child, she agreed. After supper, Varqa prescribed a pearly pill; however, before the evening was over, Mirza told his wife privately that maybe they should ask Varqa and the family to stay as their guests to see if the medicine would become effective or not. Well, she consented to that also.

Before long it was discovered that she was pregnant. Mirza told her that he had pledged to God that whoever gives them the bounty of another child, he would give his daughter to marry him. The wife felt very reluctant. Her family background and the wealth and position of Mirza made her very conceited. The thought of giving her precious daughter to a stranger who not only was a Bahá’í but also was considered by her to be below their class, was very hard to swallow. Mirza showed his concern that if he does not keep his pledge, they might lose the unborn baby. She found herself at an impasse and consented, not knowing what a bounty entered into their lives, and may God have mercy on her soul for what she did later on. How could a daughter raised by that mother have been any better. Her soul also needs our prayers. Well, you guessed it right. The next event was a big wedding for Mirza’s daughter.

Sometime after the wedding, Varqa, his father, Mulla Mihdi, and oldest brother, Husayn, took to the road on foot towards Akka. Having ill-fitting shoes, Mulla’s feet became lacerated, and by the time they reached Beirut, he was quite ill. However, he insisted that they should go on. Towards the end, Mulla nearly dragged himself, and died at Mazra’ih before attaining the presence of Bahá’u’lláh. During that time, Bahá’u’lláh resided part of the time in either Mazra’ih or Akka. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá stated that He built the grave of Mulla Mihdi with His own hands. Mulla Mihdi and Husayn, the oldest son, twice before had attained the presence of Bahá’u’lláh when He was in Baghdad, sometime before 1860. It was Mirza Husayn, who after his second visit, took the first copy of the Hidden Words to Yazd, and intimated to the friends that Bahá’u’lláh was the Promised One before Bahá’u’lláh had declared Himself. (Revelaton of Bahá’u’lláh, Vol. 4, p. 53)

Sometime after the wedding, Varqa, his father, Mulla Mihdi, and oldest brother, Husayn, took to the road on foot towards Akka. Having ill-fitting shoes, Mulla’s feet became lacerated, and by the time they reached Beirut, he was quite ill. However, he insisted that they should go on. Towards the end, Mulla nearly dragged himself, and died at Mazra’ih before attaining the presence of Bahá’u’lláh. During that time, Bahá’u’lláh resided part of the time in either Mazra’ih or Akka. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá stated that He built the grave of Mulla Mihdi with His own hands. Mulla Mihdi and Husayn, the oldest son, twice before had attained the presence of Bahá’u’lláh when He was in Baghdad, sometime before 1860. It was Mirza Husayn, who after his second visit, took the first copy of the Hidden Words to Yazd, and intimated to the friends that Bahá’u’lláh was the Promised One before Bahá’u’lláh had declared Himself. (Revelaton of Bahá’u’lláh, Vol. 4, p. 53)

Attaining the presence of Bahá’u’lláh was the first time for Varqa, and the third for Husayn, this time in Akka, and took place sometime in 1878 or 1879. It magnetized and transformed Mirza Ali-Muhammad, (Varqa) who was in his early twenties, into a spiritual giant. When he saw Bahá’u’lláh for the first time, he found Bahá’u’lláh’s face very familiar, but could not remember where or when he had seen Him before. This was puzzling him until after several times in His presence, one day Bahá’u’lláh told him: “Varqa, asnam-i uham ra bisuzan,” meaning “burn away the idols of vain imaginings.”

By hearing these words, he remembered his childhood dream. In that dream he saw himself playing in a garden with some dolls when God arrived, took the dolls away, and threw them in the fire. When his parents heard about his strange dream, he was told firmly that no one could see God, and should never repeat it, so he forgot all about it. Yes, indeed, that was when he saw Bahá’u’lláh’s face. Imagine! This was almost two decades earlier when Bahá’u’lláh was in Baghdad. He appeared in that child’s dream and made him, as Abdu’l-Baha stated, “A dedicated believer from his early years.”

Another time while in the presence of Bahá’u’lláh, a thought occurred to him that he believed in Bahá’u’lláh as the Supreme Manifestation, but how he wished Bahá’u’lláh would give him a sign to that effect. In a flash, a verse from the Qur’an came to his mind. He wished in his heart that Bahá’u’lláh might repeat that verse as a sign. Didn’t take too long when Bahá’u’lláh, in the course of His utterance, mentioned that very verse. Of course, Varqa was delighted, and overjoyed, but listen to this! He told himself, “Could this have been a mere coincidence?” Abruptly, Bahá’u’lláh turned to him and said, “Inham kafi nabud?” (Wasn’t this sufficient proof to you?”) Now Varqa was shaken and dumbfounded, but assured. Varqa never doubted Bahá’u’lláh, but it was his human way of asking for confirmations, and what a confirmation he received! He reached the pinnacle of certitude, and as a flame of fire and tower of strength, returned to Tabriz, now his home town.

He had four sons, Azizu’llah, Ruhu’llah, Valiyu’llah, and Badi’u’llah, the youngest who died in childhood.

His father-in-law, Mirza Abdu’llah, introduced him to the crown prince, who recognized his depth of knowledge and talents. So before the gatherings of the learned, the prince would tell Mirza, his chief attendant, don’t forget to bring your son-in-law, meaning Varqa. Varqa’s poetry was one of the highlights of these gatherings, and the prince would praise and honor him with precious awards. It was at one of these gatherings where an unbelievable subject was brought up, and Varqa defended the Cause. The learned clergy present said, “These Bahá’ís used to serve dates in their firesides to convert the innocent Muslims. After discovering this, people avoided eating dates in firesides. Now, they have come up with a new trick. They make extract of date into a pill which the speaker holds between his fingers. As their bewitching words make the jaws of the listeners drop open, he shoots the pill into each one’s mouth, and that is the reason for such a large number of conversions.”

Varqa, who in the past had limited himself to reading his poetry, asked the prince if he could make a comment. He said, “I have knowledge of medicine and am aware of many extracts, but never heard about the date extract. Such pill-throwing requires years of practice and marksmanship so they don’t miss the mouth, and thirdly, regardless of how eloquent a speaker, seldom does one see every jaw drop in awe, and finally, if the pill gets into the mouth, people still have to swallow it, which no one has reported.” Well, the clergy was deflated, and most likely, the prince was amused.

Varqa did extensive travel-teaching, and effectively spread the Cause, and in the process, occasionally suffered abuse. His home life was not pleasant, and the mother-in-law was the culprit.

In 1883, about four years after his return from pilgrimage, he went to his native city of Yazd. Here I can’t help but to mention how many dedicated believers have come from the hot and dry city of Yazd and its suburbs – the immortal Ahmad, the Taherzadeh family, the Yazdi family, the first two trustees of Huququ’llah, and many others. In addition, that city of narrow streets, tall draft towers, and adobe houses has offered at the threshold of Bahá’u’lláh seven martyrs during one day at three different times, the most recent was 1980. What a city! May through Bahá’u’lláh’s blessings the ignorant there and elsewhere be guided.

In 1883, about four years after his return from pilgrimage, he went to his native city of Yazd. Here I can’t help but to mention how many dedicated believers have come from the hot and dry city of Yazd and its suburbs – the immortal Ahmad, the Taherzadeh family, the Yazdi family, the first two trustees of Huququ’llah, and many others. In addition, that city of narrow streets, tall draft towers, and adobe houses has offered at the threshold of Bahá’u’lláh seven martyrs during one day at three different times, the most recent was 1980. What a city! May through Bahá’u’lláh’s blessings the ignorant there and elsewhere be guided.

The reason for Varqa returning to Yazd was to visit his only sister, Bibi Tuba, who through her letters, lamented their separation.

This talk is rather long. We have covered about one-fourth. Do you wish to take a break now? All right, a little later.

Soon after his arrival, the same leading clergyman who bastinadoed and expelled his father about five years earlier, issued Varqa’s death sentence, but the government decided to imprison him in chains with hard criminals. He spent one year in the foul prison in Yazd.(Revelation of Bahá’u’lláh, Vol. 4, p.55) Then with stocks on his feet and under chain, he was sent to Isfahan riding on a mule. You can imagine the torture of riding on a mule with the weight of stocks on the ankles for six or seven days to cover that distance. Average distance by mule or horse in those days would cover twenty-five to thirty miles from sunrise to sunset. On the way, to avoid abuse of the attendant, he pretended he was deaf and mute. After his arrival at a prison in Isfahan, a few interesting things happened.

A well-known Bahá’í poet, Sina, who had just been released from the prison, heard that a Bahá’í had been brought to that prison.

He went for a visit, but was told that the prisoner is mute. As soon as they saw and recognized each other and exchanged greetings, the prisoners shouted that the Bahá’ís performed a miracle and cured the deaf mute. This poet, noticing the foul condition of Varqa’s prison, caused his transfer with the help of other believers to the prison for dignitaries which was in better repair. Do you think that was done so easy? How could Bahá’ís who had no clout and constantly persecuted effect such a change? The story is fascinating.

Zillu’s-Sultan, the prince governor of the province, titled by Bahá’u’lláh “the infernal tree,” wished to eliminate the crown prince, and kill the king so he could get to the throne. He sent a confidant to Bahá’u’lláh in Akka to ask Him to order the believers to kill the king. Rebuffed and told by Bahá’u’lláh that the Cause of God is not a plaything for politics, the confidant returned to Iran. On one of his subversive trips to Tabriz, he was arrested by his target, the crown prince. Upon discovery of the plot, the order for execution by hanging was issued, but the chief attendant, Mirza Abdu’llah, Varqa’s father-in-law, intervened, and the confidant returned safely to Isfahan. The Bahá’ís, learning about this, went to the confidant, and told him, “Varqa, who is in the foul prison, is the son-in-law of the man in Tabriz who saved your life. Now is your turn to return the favor.” So Varqa was transferred to the prison for dignitaries, but still was in chains with stocks on his feet. That bloodthirsty prince-governor, upset and disappointed in Bahá’u’lláh’s lack of cooperation, caused the martyrdom of seven martyrs in Yazd through his son who was the governor of Yazd.

Varqa was chained to a prominent son of a tribal chief who was at odds with the government. He soon converted him, and this had a chain effect in that tribe. The prince-governor, at times, used to visit the prominent prison mate of Varqa, and Varqa’s poetry charmed them both. First, the stocks were removed from his feet, and later he was freed. Three decades later, this fiendish prince, fallen from power, was in France. Upon seeing Abdu’l-Baha in Paris, he tried to make excuses for many martyrdoms when he was a governor. In course of conversation, he said this about Varqa, “He was one of the greatest men if Iran, if not the greatest.”

Let us go to a more pleasant part of Varqa’s life, an uplift that he badly needed. Varqa was granted the privilege of a second pilgrimage. This was about one year before the Ascension of Bahá’u’lláh. He took two of his older sons, Azizu’llah and Ruhu’llah, as well as his father-in-law with him. Ruhu’llah was seven years old. In that tender age, he manifested unusual depth in the Faith. Having inherited his father’s poetic talent, his intense poetry testify to the purity of his soul, and true understanding of the station of Bahá’u’lláh. Soon, we shall witness the glow of this gifted star.

Once, to compliment Varqa, Bahá’u’lláh asked for him, and told Varqa since he had knowledge of medicine he should prescribe medicine for Bahá’u’lláh as He did not feel well. That evening, again He summoned Varqa, and told him He had taken the medicine, and as a patient, He liked His physician. Oh! What a compliment!

Another day, Varqa asked Bahá’u’lláh how the Faith would become universally accepted. Bahá’u’lláh answered, (remember this was in 1891) that the nations will fully arm themselves and like blood-thirsty beasts attack each other resulting in tremendous bloodshed. Then the wise from all nations would investigate the cause of this, and conclude that prejudice is the cause, the worst being religious prejudice. Then they would try to eliminate religion as the culprit, but soon they would realize that man cannot exist without religion. Then they would study the teachings of all religions to see which one addresses the requirements of the age. That is the time that the Faith would become universal.

Another day, Varqa asked Bahá’u’lláh how the Faith would become universally accepted. Bahá’u’lláh answered, (remember this was in 1891) that the nations will fully arm themselves and like blood-thirsty beasts attack each other resulting in tremendous bloodshed. Then the wise from all nations would investigate the cause of this, and conclude that prejudice is the cause, the worst being religious prejudice. Then they would try to eliminate religion as the culprit, but soon they would realize that man cannot exist without religion. Then they would study the teachings of all religions to see which one addresses the requirements of the age. That is the time that the Faith would become universal.

Then Bahá’u’lláh spoke about the heavenly qualities of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá. He said in the world there exists a phenomenon that in various tablets He had referred to as the Most Great ELixir. Christ had this phenomenon, and see what influence He exerted upon the world after His crucifixion. He truly revolutionized the world. Then He said,”Look at the Master who so patiently deals with all kinds of people. He also possesses this power.” Varqa then realized who would succeed Baha’ullah, and was filled with joy. He prostrated at the feet of Bahá’u’lláh, and begged Him to accept him and one of his sons as a sacrifice in the path of Abdu’l-Baha, to which Bahá’u’lláh consented.

Begging for martyrdom might sound rather strange to some of you. Please permit me to quote from Adib Taherzadeh’s book, Revelation of Bahá’u’lláh. (Volume 4, page 57) “It is not possible for those of us who have not reached that level of utter devotion to Bahá’u’lláh, and have not become intoxicated with the wine of His revelation, to understand the motive of a high-minded person, talented and well-balanced, in seeking to give his life for the Cause. These people who sought martyrdom must have attained the pinnacle of faith and assurance. They must have seen with their spiritual eyes a glimpse of the inner reality of their Lord.. .In most cases, Baha’u’lllah discouraged the friends, and in His tablets urged the believers to protect their lives so they could teach the Cause.” Perhaps you know that a pioneer who dies while pioneering in a foreign land has the station of a martyr. (Bahá’u’lláh, Messages from the Universal House of Justice, 1968-1973, p. 102)

Apparently, Varqa wanted to make sure he had heard right, so after his return he wrote to Bahá’u’lláh about his wish which had been granted, and Bahá’u’lláh confirmed it in writing. After the Ascension, when Varqa attained the presence of Abdu’l-Baha, he made a reference to that promise and the Master also confirmed it. So you see, the martyrdom was inevitable. Maybe I should stop here because you know the ending.

Let us continue, and see what seven-year-old Ruhu’llah did during that pilgrimage, and how he flourished. He truly was a spiritual prodigy. One day, Bahá’u’lláh asked Ruhu’llah, “What did you do today?” He answered, “I attended a Bahá’í class.” Bahá’u’lláh said, “What was the subject?” He answered, “The return of the prophets “Will you explain it?” He answered, “The return of the prophets.” “Will you explain it?” Bahá’u’lláh praised the child, and often called him Jinab-i-Mobaligh, meaning his Honor, the Bahá’í teacher.

This was easy compared to the next occasion which shows how sharp Ruhu’llah’s faculties were. Once Bahá’u’lláh asked him, “What did you do at home?” He answered that he taught the Faith, and told people that the Promised One has come. Now comes the tough question that I am not sure how an adult would have answered it. Bahá’u’lláh said, “What would you do if it were found that the message of the Bab was not authentic, and the true Promised One appeared?” The young boy instantaneously answered, “I would try to teach him the Bahá’í Faith.” Imagine how accurate, how deep and how spontaneous! I wish I were worthy enough to say, “Bravo.” Ruhu’llah received well-deserved praise from his Lord. Ruhu’llah was not an ordinary child. At his young age he composed beautiful poetry, and he would speak about the Faith in gatherings of the clergy and men of learning. His answers were simple, but profound.

After his return to Tabriz, Varqa continued his extensive travel- teaching, and one of his converts is the subject of the next exciting story. Before I tell you, don’t you wish you could be in Varqa’s home, and hear the conversations of the young Ruhu’llah with the hostile grandmother? No doubt both his mother and grand- mother were a handful, but I have a notion they were no match to that young spiritual giant.

One of the converts you are going to hear about was the artist who made a portrait of the Báb. His name was Aqa Bala Big-i-Naqqash Bashi. Naqqash Bashi means the chief artist in the court of the crown prince. After his conversion, he told Varqa how in Urumiyih the Bab rode the unruly horse which the mayor had given Him to test Him. He said, “I was among the anxious crowd who flooded the house of the mayor to have a glance at the miracle maker, the Báb. After seeing Him, I decided to draw His picture so I focused intently upon His face. When the Bab noticed me, He fixed His cloak on His knee, and posed with His hand on the cloak.” Obviously, the Báb understood the intention of the artist who was among the crowd. They had not been introduced. To continue the narrative, “I left the room, and made a rough sketch on a paper, and went back a couple more times. Every time I went in, the Báb resumed the same position and would look at me.” Oh! What a majestic scene! He later composed a full scale portrait in black and white.

One of the converts you are going to hear about was the artist who made a portrait of the Báb. His name was Aqa Bala Big-i-Naqqash Bashi. Naqqash Bashi means the chief artist in the court of the crown prince. After his conversion, he told Varqa how in Urumiyih the Bab rode the unruly horse which the mayor had given Him to test Him. He said, “I was among the anxious crowd who flooded the house of the mayor to have a glance at the miracle maker, the Báb. After seeing Him, I decided to draw His picture so I focused intently upon His face. When the Bab noticed me, He fixed His cloak on His knee, and posed with His hand on the cloak.” Obviously, the Báb understood the intention of the artist who was among the crowd. They had not been introduced. To continue the narrative, “I left the room, and made a rough sketch on a paper, and went back a couple more times. Every time I went in, the Báb resumed the same position and would look at me.” Oh! What a majestic scene! He later composed a full scale portrait in black and white.

Varqa wrote to Bahá’u’lláh about this tremendous discovery. Bahá’u’lláh instructed Varqa to have the artist make two water color copies, one to be sent to Himself, and the other to be kept by Varqa. When Bahá’u’lláh received this copy, the brother of the wife of the Bab, Afnan-i-Kabir, was in Akka. Bahá’u’lláh asked him how much did the drawing resemble the Bab, and he confirmed that it was an accurate likeness. Then Bahá’u’lláh sent his own fur overcoat as a gift to the artist.

Unfortunately, during Varqa’s later imprisonment in Tehran, this drawing (Varqa’s copy) and many other precious items were confiscated by the captors. Abdu’l-Baha has stated that in the future this portrait and other relics will be returned to the Varqa family. The original portrait in black and white which was kept by the artist was found much later by a believer, Siyyid Asadu’llah-i-Qumi, who took it to the Holy Land and presented it to Abdu’l- Baha.

This is a good time to take a break. This exciting story is rather long, and I prefer not to sacrifice any details in the interest of time. Let us pause now.

As you were having your break, I looked through the side window and saw what nearly curdled my blood. I saw a monstrous serpent stalking Varqa. Was it a she-serpent? Most probably. I saw something like a flood, but the water was the color of blood. Then I saw the eye of a fierce storm approaching these heavenly doves. I wanted to see no more. As I shut my eyes, you came back. Please ignore the unpleasant things I just told you. Let us see what happened next.

The last and third trip to Akka was in 1893, one year after the Ascension of Bahá’u’lláh. Varqa took the two oldest sons, Azizu’llah and Ruhu’llah (now nine years old) to the presence of Abdu’l-Baha. The Master and His sister, the Greatest Holy Leaf, showed special admiration and love for Ruhu’llah. One day, Ruhu’llah, his brother and other children were playing outside when the Greatest Holy Leaf asked Ruhu’llah and his brother to come in. Also in the room were the two sons of Bahá’u’lláh, Mirza Badi’u’llah and Mirza Diya1u’llah. These two later joined their older brother, Mirza Muhammad- Ali, and rose against Abdu’l-Baha, and thus became covenant-breakers.

The Greatest Holy Leaf asked Ruhu’llah’s older brother, “What did you do while in Persia?” Ruhu’llah answered, “We taught the Faith.” She asked, ‘By saying what?” He replied, “God has manifested Himself.” Rather surprised, she said, “Tell me, did you tell this to everyone?” He said, “No, only to people who were receptive.” “How could you tell who was receptive?” she asked. “By looking into their eyes, ” was his answer. She laughed heartily, and told Ruhu’llah, “Come and look into my eyes, and tell me what do you see.” He came and intently looked into her eyes, and said, “You already believe in those words.” Now listen to this about the two young sons of Bahá’u’lláh and Ruhu’llah’s insight. She asked him to look into the eyes of the two sons of Bahá’u’lláh, who were doing their school work. He looked into their eyes searchingly, and commented, “They are not worth looking into.” Imagine saying that about two sons of Bahá’u’lláh who were respected by everyone, and who had not yet shown any signs of covenant-breaking. This power of seeing the future of those youth was beyond the power of an ordinary child. As was mentioned before, his poetry demonstrates the depth of his faith, and understanding of the real purpose of life.

The Greatest Holy Leaf asked Ruhu’llah’s older brother, “What did you do while in Persia?” Ruhu’llah answered, “We taught the Faith.” She asked, ‘By saying what?” He replied, “God has manifested Himself.” Rather surprised, she said, “Tell me, did you tell this to everyone?” He said, “No, only to people who were receptive.” “How could you tell who was receptive?” she asked. “By looking into their eyes, ” was his answer. She laughed heartily, and told Ruhu’llah, “Come and look into my eyes, and tell me what do you see.” He came and intently looked into her eyes, and said, “You already believe in those words.” Now listen to this about the two young sons of Bahá’u’lláh and Ruhu’llah’s insight. She asked him to look into the eyes of the two sons of Bahá’u’lláh, who were doing their school work. He looked into their eyes searchingly, and commented, “They are not worth looking into.” Imagine saying that about two sons of Bahá’u’lláh who were respected by everyone, and who had not yet shown any signs of covenant-breaking. This power of seeing the future of those youth was beyond the power of an ordinary child. As was mentioned before, his poetry demonstrates the depth of his faith, and understanding of the real purpose of life.

Another time, while playing, one of the playmates said indecent words, and was chastised by Ruhu’llah which made his mouth bleed. Children ran to the pilgrim house to inform Varqa. Ruhu’llah, knowing what was coming, ran to ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s house, and entered His room where Abdu’l-Baha told him to sit down. As ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s back was towards the window, Varqa appeared at the window, and beckoned Ruhu’llah to come out, but Ruhu’llah kept nodding his head meaning “no.” ‘Abdu’l-Bahá said,”What is wrong that you keep moving your head.?” He admitted what he had done. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá called Varqa in, and strongly cautioned him never to treat Ruhu’llah harshly. From then on Varqa treated his young son with respect. That made it apparent to Varqa which of his three sons would have the honor of martyrdom with him as he had requested in the past from Bahá’u’lláh. As was said before, in our spiritual level it is impossible to comprehend the desire for martyrdom and its significance in the Worlds of God.

After their return to Tabriz, Varqa’s mother-in-law, seeing how the grandchildren were being raised with Bahá’í spirit, intensified her hostility. She demanded that Varqa must divorce her daughter. In that culture, only men could divorce. Varqa’s father-in-law disapproved of it, and advised Varqa to keep distance by travel- teaching throughout the large province. The storm of the mother- in-law picks up momentum, but what it does to Varqa we shall see. The situation turns hectic. Other adverse events feed this storm, but Varqa’s wings are strong.

The enemies of Varqa’s father-in-law, the prominent man, poisoned the good-will of the crown prince by accusing the father-in-law of holding secret meetings with Bahá’ís, plotting his assassination. As soon as Mirza heard about it, he left Tabriz for Tehran, the capital.

The mad mother-in-law, seeing the coast clear, implemented her first near-fatal strike. She went to a leading clergyman, who also was a relative, telling him the activities of her son-in-law, and asked him to issue a death sentence. You might smile at the legal system in those days, some of it still existing in Iran. He did not care about the Faith, but being fair minded, said, “How can I issue such a verdict, not knowing the accused? She said, “No problem. I will easily prove it to you.” She went home to Ruhu’llah, and said, “A friend of your father wishes to meet you.” Ruhu’llah accompanied her to the house of the clergyman, thinking he was a Bahá’í friend of his father, and greeted him with “Allah’u’Abha” which did not set too well with the clergyman.

After exchange of a few pleasantries, she said that her grandson, less than ten years old, could recite the obligatory prayer by heart. “Let us hear it,” was the man’s response. Ruhu’llah asked for the direction of the Qiblih, and after ablution, recited the long obligatory prayer with all of its positions. Spellbound by the sweetness of his voice, and impressed by the holy words, as soon as he finished the prayer, the clergyman angrily turned to the grandmother, and said, “You should be ashamed of yourself asking me to issue a death sentence for a man who raises such a God-worshipping son,” and told her to leave at once.

Frustrated, yes, but defeated, no. Her will was as strong as her wealth and social standing. She was resolved to destroy Varqa, and nothing could stop her. She always got anything she wanted except her son-in-law, Varqa, who was forced on her.

Now she decided to take the matter into her own vicious hands. Will this storm sweep Varqa off his feet before he could cherish the promise of his Lord, or is this the end?

Let us direct the window towards Varqa’s mother-in-law’s mansion, and see what transpired in the private quarters. She called her trusted and husky servant, and offered a very generous reward should he oblige her by killing Varqa. Maybe she said how distressed she was with her husband fleeing the city, and Varqa’s waywardness. He was stone-faced about the whole thing. Could it be the reward was not high enough? But it was more than generous. Well, what do you think? His master, who was fond of Varqa, had fled the city, and now the lady is in charge and could protect him. Maybe he needs time to think it over. To her, every step of this plan so far was progressing well, and there was no reason that this one should fail. After all, the servant, a good Muslim, should be glad to get rid of that heretic, Varqa.

Let us direct the window towards Varqa’s mother-in-law’s mansion, and see what transpired in the private quarters. She called her trusted and husky servant, and offered a very generous reward should he oblige her by killing Varqa. Maybe she said how distressed she was with her husband fleeing the city, and Varqa’s waywardness. He was stone-faced about the whole thing. Could it be the reward was not high enough? But it was more than generous. Well, what do you think? His master, who was fond of Varqa, had fled the city, and now the lady is in charge and could protect him. Maybe he needs time to think it over. To her, every step of this plan so far was progressing well, and there was no reason that this one should fail. After all, the servant, a good Muslim, should be glad to get rid of that heretic, Varqa.

Let me tell you a secret that she does not know. It is rather significant, and the life of Varqa depends on it. Well, the servant had been converted by Varqa to become a dedicated Bahá’í. Keep this to yourself, and wait and see what did the servant do. No, he did not kill her, instead. I told you he was a good Bahá’í. Well, by now you can tell that this storm turned into a breeze, and bypassed Varqa, but still you like to know what did the servant do. He did what any decent person would do. He privately informed Varqa about her resolve, and that when disappointed in him, she would hire another assassin who would undoubtedly finish the job.

This left Varqa with no choice except to leave the house quietly in the middle of the night. He already had lowered his books and tablets through a window to the sidewalk. He went to a believer’s home. The next morning when his wife and mother-in-law had taken the youngest son to the public bath, he returned home, and took his two older sons, Azizu’llah and Ruhu’llah, with him.

Varqa wrote to his father-in-law, now in Tehran, about the situation. He answered by advising Varqa to divorce his wife, and that he was doing the same. The mother and daughter went their own ways. Both remarried, but ended miserably. As for the degree of hatred of the mother-in-law, it is sufficient to say that when she heard about Varqa’s martyrdom, she gave a festive banquet celebrating the news. May God have mercy on her soul.

What do you think happened to the youngest son of Varqa, Valiyyu’llah, who was left behind? Well, his mother and grandmother were not going to let him slip through their fingers both physically and spiritually. The grandmother was determined to raise him as a Muslim. One of her brainwashing techniques was that every day while praying he had to sit by her. At the end of prayer, she would supplicate to God in these words, “0 God, should this boy become a good Muslim give him a long and prosperous life, and if not, take his life before he gets any older.” He was required to say amen to that. That kind of polluted atmosphere brought great grief and confusion to young Valiyyu’llah. After reaching adulthood, his uncle, Mirza Husayn, rescued him, and washed away all the impurities instilled into his innocent mind. He became a devoted believer, and later on attained the presence of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá. During the ministry of Shoghi Effendi, that son of the illustrious Varqa, became the trustee of Huququ’llah, and later on, a Hand of the Cause. Jinab-i-Valiyyu’llah-i-Varqa passed away at the age of seventy-one in 1955. He lived a long, prosperous life as supplicated by his ignorant grandmother who did not know that a good and true Muslim is none other but a devoted Bahá’í.

Now we are entering a calm period between the storms in the life of Varqa. Varqa left his second home-town of Tabriz with heavy heart, and headed for the city of Zanjan, taking his two older sons with him. He had visited that city three times before on his trips to Tehran. They stayed with Urn-i-Ashraf, one of the great who had lost her husband and son as martyrs, and the recipient of many tablets from Bahá’u’lláh. After some time, Varqa married her granddaughter, Liq’iyyih Khanum.

During those peaceful couple years, Varqa continued his teaching activities, and most likely, the two sons enjoyed their new life in a loving Bahá’í atmosphere, free of sarcasm which they had to endure before.

Let’s focus our vision on one of the dusty little streets of old Zanjan where Ruhu’llah and his older brother were walking. A mulla, meaning an Islamic priest, riding a donkey, noticed from their clothing that they were not native boys. Being curious, he slowed down his donkey, and asked, “Whose boys are you?” Ruhu’llah, usually being the spokesman, answered, “Sons of Varqa from Yazd.” “What is your name?” asked the mulla. “Ruhu’llah,” was the answer. The mulla said, “Wow! What a great name. That is the title of Christ who brought the dead to life.” Ruhu’llah answered, “If you stop your donkey, I shall do the same to you.” The mulla, whipping his donkey, said, “You must be Bahá’ís.” Definitely, he was not a receptive soul.

Now about two and a half years had passed since Varqa and sons had moved to Zanjan. Rumors could be heard that this newcomer, the teacher from Yazd, meaning Varqa, had come to Zanjan to mislead the Muslims.

Forecast after forecast, indicated the approach of a destructive storm. Remember the eye of the fierce hurricane I told you about. The deadly attempts of the mother-in-law were now behind, and Varqa was safely out of her reach. Varqa, appearing so calm and serene and intensely teaching the Cause, had this anguish in his heart, such yearning in his soul that was consuming his whole being. How much longer, where and how? These were his unspoken words about the promise, the written promise and the confirmed promise. After all, it had been a long nineteen years since his Lord granted his wish. Nineteen is a significant number. Didn’t Bahá’u’lláh delay His Declaration until nineteen years had passed from the Declaration of the Bab? That must be it, the number nineteen. Varqa had reached the pinnacle of faith and certitude. As his poems testify, his heart and soul were focused on love of Bahá’u’lláh, and that was the flame that was consuming him.

Forecast after forecast, indicated the approach of a destructive storm. Remember the eye of the fierce hurricane I told you about. The deadly attempts of the mother-in-law were now behind, and Varqa was safely out of her reach. Varqa, appearing so calm and serene and intensely teaching the Cause, had this anguish in his heart, such yearning in his soul that was consuming his whole being. How much longer, where and how? These were his unspoken words about the promise, the written promise and the confirmed promise. After all, it had been a long nineteen years since his Lord granted his wish. Nineteen is a significant number. Didn’t Bahá’u’lláh delay His Declaration until nineteen years had passed from the Declaration of the Bab? That must be it, the number nineteen. Varqa had reached the pinnacle of faith and certitude. As his poems testify, his heart and soul were focused on love of Bahá’u’lláh, and that was the flame that was consuming him.

He did not wish to become the cause of another upheaval in Zanjan, the city where erudite and fierce Hujjat with 1,800 believers gave up their lives defending their faith. Since that episode four decades earlier, that city had witnessed many atrocities. Having had instructions from ‘Abdu’l-Bahá to move the tablets and books out of Zanjan, Varqa felt prompted to move to Tehran. The plan was to take his two sons with him, and the wife would join them later. This also would give him a chance to see his ex-father-in-law who now resided in Tehran.

A tablet from ‘Abdu’l-Bahá arrived, stressing steadfastness in the face of fierce storms of tests. The dream of Varqa’s wife, identical to the dream of a Muslim acquaintance, about a flood the color of blood was foreboding danger. (Masabih Hidayat, p.107) He had to leave at once, but it was in the dead of winter with roads closed. Horse and mule owners were not willing to tackle the deep snow and ice. As days dragged on, Azizu’llah, the eldest son, became restless, and without informing anyone took the road to Tehran on foot. Everything, including tablets and books, were packed in trunks and sealed, ready to go. Only if the weather would cooperate. Finally the pack-animal owners sent a message that next day they would start.

That final night in Zanjan proved not to be their last night there, even though they left early the next morning. That night Varqa, his new father-in-law, and Mirza Husayn, a Bahá’í friend, decided to visit the head of the telegraph office, who was a friend, to say goodbye, and also extend their sympathy for the recent death of his mother. As they were leaving the telegraph office, they were detected by an evil mulla who immediately reported them to the police, and the governor was informed. You might wonder what made it so reportable. In those days, going to the telegraph office had the connotation of possibly sending a petition or complaint to the capital. The governor, having very recently been appointed, was very suspicious. He had no idea that Varqa would be leaving early the next morning accompanied by Ruhu’llah, now twelve years old, and Varqa’s father-in-law, Haji Iman.

The next day the governor summoned the believers for questioning. After arresting Mirza Husayn, the attendants reported to the governor that the rest of them had left the city. So the governor ordered his stable master to take men and the fastest horses and intercept Varqa, which they did. Fortunately and miraculously, the pack-animal carrying two trunks full of tablets, books and archival material was not halted. These were taken by the mule driver to the next city, Qazvin, and delivered to a believer.

As we get drawn more into these adverse events, you should realize the timing of it all. This was the year of jubilee celebration of fiftieth year of the coronation of the king, Nasiri’d-Din -Shah, during which the whole country participated in some way. Each sizeable city sent a company of soldiers and their equipment to the capital, Tehran, for honoring the occasion. Being exact, the years was 1896, four years after the Ascension of Bahá’u’lláh.

The final events in the city of Zanjan and what followed to the very last hour in the life of Varqa is from the written memories of Mirza Husayn Zanjani who was in chains with Varqa and Ruhu’llah.

As you recall, Mirza Husayn stayed behind in Zanjan when Varqa and party had left the city. Mirza Husayn was arrested shortly after that because he had accompanied Varqa to the telegraph office, and he was in chains and stocks when Varqa, Ruhu’llah and Haji Iman were intercepted and returned to Zanjan.

The governor became delighted at seeing Varqa captured, and abused him verbally. Varqa, in answer, said, “It is not very becoming of a great man to such words to a person he does not know.” The governor calmed down, and somewhat impressed, told the attendant to take Varqa and Ruhu’llah to his own quarters and only chain them at night. He even allotted an allowance for their expenses, but the attendant barely used a quarter of it for their food. Haji Iman, the father-in-law, was taken to jail and chained with Mirza Husayn.

Their detention in Zanjan lasted sixteen days. Many people, hearing about them, would come to the jail to see how Bahá’ís look, just like going to a zoo. The onlookers showed their surprise that they looked like humans and not exotic animals. It should not surprise you to hear that up to present, the ignorant and fanatic are told and believe that Bahá’ís have tails. Amazing, how much lies and rubbish the clergy introduce t o the minds of the gullible.

During those sixteen days, Varqa had to endure repeated verbal assaults by the clergy and the governor. You see, this was during the month of Ramadan which is the Islamic fast when many people stay up at night and sleep during the fasting hours of the day. At the governor’s directions, encounters were arranged between Varqa and the clergy every night after breaking the fast, into the early hours of morning. The governor attended most of them. It was like the evening show, late show and the late-late show for the people to come and go as they pleased, and entertain themselves. At times, the governor had to intervene in the fights among the clergy due to contention on how to respond to Varqa.

I thought I bypass the details of those sixteen days, but it would be shortchanging you. Two incidents will give you an idea of what kind of foolishness Varqa had to deal with, and another one will show you a contrast.

One evening a mulla told Varqa, “I can reveal words similar to Bahá’u’lláh.” We should put ourselves in the place of Varqa, and see how could we have responded to such assertion in that hostile gathering. Let us think for a while. The assertion of that mulla was that he could equally reveal words like Bahá’u’lláh. We could possibly answer that Bahá’u’lláh’s words are powerful and have influence. I don’t think that would be so convincing a century ago, particularly when every mulla had a bunch of devoted followers, and the Faith did not have the worldwide spread of today.

In those days, these expert Bahá’í teachers such as Abu’l-Fadl, Varqa, and other used three methods in teaching the Faith. One was through the holy words of the past and prophecies. The second was through logic and reason. The third method was used only when the intention of the non-Bahá’í was to argue. In such occasions, the Bahá’í teacher used the words of the contender against himself in defense of the Faith. Listen and learn the mastery of Varqa.

Varqa asked, “After revealing them, should someone ask you whose words are these, what would you answer?” He said, “Of course, mine.” Varqa said, “But Bahá’u’lláh states His words are from God, and people from every religious background have accepted them and given their lives in His path. Now let us be fair. Please provide only one witness from the crowd here to testify to your superior knowledge.” No one said a word. Now the ball was in Varqa’s court. He said, “What other proof is there for the truth of Islam except for the holy words of the Qur’an and their in£luence?” The mulla retorted, “We have other proofs.” Varqa said, “Such as?” The mulla said, “The traditions of the Imams and the like.” Another mullas in the group shouted, “Mulla, you really messed it up. You don’t accept the words of Muhammad Himself as primary proof, and claim the words of His subordinates to prove the validity of Islam. Now the sword you handed to Varqa will to Zanjan, and besides, his son-in-law was the intepreter for the Russian consulate. Your involvement in his execution might be detrimental for you. Why not send him also with us to Tehran, and let someone else be the instrument?” After a long pause, the governor agreed to send them all in custody of the commander of a cavalry company headed for the jubilee in Tehran. Depravity and meanness being their characteristic, they had to charge the family of the prisoners for the expenses of the horses used for their travel. In recent events in Iran one century later, their torture-monger descendants have continued the disgusting trait by forcing the family to pay for the cost of bullets used to martyr the believers.

Varqa asked, “After revealing them, should someone ask you whose words are these, what would you answer?” He said, “Of course, mine.” Varqa said, “But Bahá’u’lláh states His words are from God, and people from every religious background have accepted them and given their lives in His path. Now let us be fair. Please provide only one witness from the crowd here to testify to your superior knowledge.” No one said a word. Now the ball was in Varqa’s court. He said, “What other proof is there for the truth of Islam except for the holy words of the Qur’an and their in£luence?” The mulla retorted, “We have other proofs.” Varqa said, “Such as?” The mulla said, “The traditions of the Imams and the like.” Another mullas in the group shouted, “Mulla, you really messed it up. You don’t accept the words of Muhammad Himself as primary proof, and claim the words of His subordinates to prove the validity of Islam. Now the sword you handed to Varqa will to Zanjan, and besides, his son-in-law was the intepreter for the Russian consulate. Your involvement in his execution might be detrimental for you. Why not send him also with us to Tehran, and let someone else be the instrument?” After a long pause, the governor agreed to send them all in custody of the commander of a cavalry company headed for the jubilee in Tehran. Depravity and meanness being their characteristic, they had to charge the family of the prisoners for the expenses of the horses used for their travel. In recent events in Iran one century later, their torture-monger descendants have continued the disgusting trait by forcing the family to pay for the cost of bullets used to martyr the believers.

They did not have the decency of letting Varqa ride a horse with a regular saddle. His horse had filled saddle bags which made riding very painful because of the stocks on his feet. At times, he said that it felt as if his legs were coming off his body. Stocks are two heavy blocks of wood locked on each ankle. The attendants brought a long chain to chain Varqa and Mirza Husayn together, but found it impractical for the long ride to Tehran on separate horses. Therefore, Mirza Husayn ended up carrying the entire chain on his neck all the way to Tehran, in addition to the stocks on his feet. But ironically, he survived the whole ordeal to relate to us the terrible chain of events in the life of Varqa.

At their first stop for overnight, the three were given a room, but soon the attendants came and took them to encounter the notables and mullas. They saw soldiers lined up, armed with rifles ready to shoot. Seeing that, it occurred to Varqa and Mirza Husayn that they moved them out of Zanjan to be killed in that village. After being confounded by Varqa’s answers, one mulla shouted, “Why aren’t such heretics killed? You faithful Muslims, what are you waiting for? Let us kill them.” No one responded to such a wrathful call. Maybe the soldiers were posted to keep the order.

As soon as they were baffled by Varqa’s knowledge and audacity, they focused on Ruhu’llah, not knowing his depth. Upon questioning, Ruhu’llah said, “I am like you folks.” They all became delighted, thinking he meant that he was a Muslim. Varqa interrupted their joy, and to their chagrin, said, “Ruhu’llah means he has followed the faith of his father just the way you gentlemen have blindly followed the faith of your fathers.” By hearing this, their rage had no bounds. They again began their noisy call for blood, “Why don’t you kill them, seeing how they insult your clergy?” Again no one made a move. Defeated by lack of response, the clergy said, “Why should Ruhu’llah’s feet not be in stocks?” Then a carpenter was called into fit the stocks on his ankles. The carpenters howed such exuberance, as if he were given the reward of this world and the next.

The commander of the cavalry and his officer in charge of the believers were fair-minded. They served them proper meals, but one attendant was mean, particularly towards Varqa. You can imagine on those cold, snow-covered roads how painful it would be to ride over a saddle bag with your thighs apart and the weight of the stocks hanging on each ankle. As if this was not bad enough torture for Varqa, the attendant at times would whip Varqa’s horse for the sudden jerk to hurt him even more. Many of these ignorant people believed, and still believe, that the more vicious they could treat the Bahá’ís, the higher their reward would be in heaven. What a surprise awaiting them! Anyway, once when the attendant ignored the instruction of his superior not to torment Varqa, Varqa told him,”May God judge between you and me.” The attendant, quite angry, galloped his horse to a spot by a spring to relax and smoke. As the cavalry got closer, they saw him on the ground writhing in pain. He was shouting, “My belly is on fire. I am dying. Help me.” Varqa prescribed some remedy, but shortly the attendant died. Now look at Varqa’s benevolence. He felt guilty because he thought it was his words which caused the man’s suffering and death. He said had he known that his wishes would be so quickly answered, he should have prayed for his guidance. He said we should never curse our ignorant enemies, but pray for them. Here I wish to interject that those of us who believe in Bahá’u’lláh and have His teachings are more answerable for our actions than the ignorant.

The officer in charge of the prisoners, at the end of the trip, became a Bahá’í. How could he have done otherwise after witnessing everything first-hand. Upon their arrival in Tehran, they were placed in the stable of the father of the commander of the cavalry. The next day, Azizu’llah, the oldest son of Varqa who had left Zanjan earlier, came to visit them. Varqa advised him not to return for the fear of being recognized and arrested. That day they took the prisoners in chains, surrounded by guards and attendants with the executioners, dressed in red, in the forefront. The usual multitude of onlookers gathered to watch the march. They were taken for interrogation to the government building where they were sentenced to be imprisoned. The prison chosen for them was where sixty notorious highway robbers and murderers were kept in chains. They brought their heaviest chain, Qara Guhar, nearly one hundred- ten pounds, which forty-fouur years earlier had been placed on Bahá’u’lláh’s blessed neck. All four- Varqa, Ruhu’llah, Mirza Husayn, and Haji Iman, Varqa’s father-in-law, were chained together. Ruhu’llah’s tender neck and body could not support the weight, so they put a wooden support for his segment of the chain.

The officer in charge of the prisoners, at the end of the trip, became a Bahá’í. How could he have done otherwise after witnessing everything first-hand. Upon their arrival in Tehran, they were placed in the stable of the father of the commander of the cavalry. The next day, Azizu’llah, the oldest son of Varqa who had left Zanjan earlier, came to visit them. Varqa advised him not to return for the fear of being recognized and arrested. That day they took the prisoners in chains, surrounded by guards and attendants with the executioners, dressed in red, in the forefront. The usual multitude of onlookers gathered to watch the march. They were taken for interrogation to the government building where they were sentenced to be imprisoned. The prison chosen for them was where sixty notorious highway robbers and murderers were kept in chains. They brought their heaviest chain, Qara Guhar, nearly one hundred- ten pounds, which forty-fouur years earlier had been placed on Bahá’u’lláh’s blessed neck. All four- Varqa, Ruhu’llah, Mirza Husayn, and Haji Iman, Varqa’s father-in-law, were chained together. Ruhu’llah’s tender neck and body could not support the weight, so they put a wooden support for his segment of the chain.

From the very first day, the captors, high and low alike, began looting Varqa’s belongings. Hajibu’d-Dawlih, the murderer-to-be, who was the highest in rank and in charge of the torture and execution of all who were considered enemies of the state, took the portrait of the Bab, and gave it to the king. The next in line insisted on taking a white robe which had belonged to Bahá’u’lláh. Varqa begged in vain for him to leave it alone. Not only did he take it, but the depraved man appeared dressed in it, to taunt Varqa. At the end, when all was gone, Varqa remarked that everything precious was taken away, but it was a worthwhile sacrifice in the path of God.

Mirza Husayn writes that they had fastened the heavy chains on them in order to be bribed for exchange for a lighter chain. Since they did not have any money, the chains stayed on. They even starved them. There was a well-to-do man who had been disfavored by the government, but was allowed to keep a servant in prison to attend his needs. The captors tried to starve the Bahá’ís by not giving them the usual meager prison ration. The wealthy man, seeing the situation, ordered the favorite Persian dish of chelo-kabab for all prisoners. Every prisoner was given a dish except the Bahá’ís. When the servant told the rich man about what the attendant had done, he flew into a rage and ordered a new supply of deluxe chelo-kabab with all garnishings for the Bahá’ís, who savored it after days of starvation. Imagine the first round when in front of starving Bahá’ís, dishes were passed to others. If you have ever tasted and smelled chelo-kabob, you the jovial prisoners so excited about the nearness of the jubilee. They were talking that the king had pledged to pardon and release all prisoners on that occasion, so they could pray in gratitude for his long life. At that time the king was sixty-five years old. Those agonizing hours did not last too long when the eye of that ferocious storm swiftly changed direction. The velocity of the storm is now building up by the minute.

Then came that fatal Friday before the day of jubilee. Being exact, the first day of May, 1896. The king had been in the habit, on Fridays, of going to a shrine near Tehran. How could he miss it on this festive and historical occasion? An anarchist pan-Islamist political faction, which was both anti-monarchy and anti-Bahá’í, hearing that Varqa and a few Bahá’ís were thrown into the prison and a trunk full of Bahá’í books was confiscated, found the timing perfect to strike. They plotted the assassination of the king, being certain that Bahá’ís would be blamed for it. You see, forty- four years earlier, three revengeful young Babis, inflamed by the martyrdom of the Bab, tried to kill the same king which failed. That time the king was about twenty years old. Well, in their calculation they had nothing to lose. One bullet and two targets. The king dead, and the Bahá’ís massacred.

Their assassin hid within the shrine, and on that bloody Friday, when the king entered the interior of the shrine, he pretended to deliver a petition to the king, when at point-blank, he shot the king in the heart. The Prince of Oppressors, as Bahá’u’lláh named that king, dropped dead. As it had to be, even his death did not stop the oppressive measures he and his underlings had viciously championed during the dark and long period of his reign.

As soon as the fiendish Hajibu’d-Dawlih, the top man who had taken the Bab’s portrait from Varqa, heard about the king’s assassination, his blood began to boil. He was the same person who forty-four years earlier, after the attempt on the life of the king, was badly frustrated at not being able to kill Bahá’u’lláh. Remember, how he took a servant of a prominent Babi, who had defected, a few times to the Siyah-Chal to identify Bahá’u’lláh as a plotter? The servant had seen Bahá’u’lláh numerous times in his master’s home, but in the prison he denied ever seeing Bahá’u’lláh before. Now the king is dead, and he has one of the prize followers of Bahá’u’lláh in his vicious clutches.

He, without the knowledge and authorization from the prime minister, rushed to the prison taking a few attendants and executioners with him. He barged in the prison like a mad dog with his face red with rage. He shouted that all prisoners should be locked in chains and stocks. The terror-stricken prisoners, not knowing what had happened, went numb.

Mirza Husayn writes, “They took the four Bahá’ís chained together to the prison yard supposedly for questioning. When we saw the soldiers on the rooftops with their guns pointing at us, and the executioners dressed in red, we sensed this was no trial. The attendant in charge of keys was told to unlock the chains of Varqa and Ruhu’llah. The atmosphere was so tense that due to shaking of his hands, he could not do it, and someone else had to do it. They took Varqa and Ruhu’llah through a long corridor, and slammed the door shut. When we saw an attendant bringing the bloody dagger of Hajib to wash it in the courtyard pool, and then another man walking away with Varqa’s clothes, we knew what was done to him, but had no idea about Ruhu’llah. Then after a thumping sound, the doors were flung open, and the panic-stricken Hajib dashed out saying, ‘The other two should wait until tomorrow.”‘ That tomorrow never came.

The timing of martyrdom was about two and half hours before sunset. Mirza goes on to state, “When Haji Iman, Varqa’s father-in-law, and I were taken back to the prison, we found our bedding and all belongings gone. We were so schocked and numb by what we saw in the courtyard that we sat speechless on the damp floor of the prison.”

How exactly Varqa and twelve-year-old Ruhu’llah were martyred, as brutal as it was, must be stated for the sake of history. How badly this narrator wishes that he could be excused from recounting such unspeakable atrocity. Friends,this is not an ordinary scene. This is the gory arena where ravenous bloodthirsty beasts are unleashed against the innocent. This is the gruesome scene of martyrdom and sacrifice, and yet it is the sacred altar of love and immolation where Varqa’s cherished desire was finally fulfilled.

How exactly Varqa and twelve-year-old Ruhu’llah were martyred, as brutal as it was, must be stated for the sake of history. How badly this narrator wishes that he could be excused from recounting such unspeakable atrocity. Friends,this is not an ordinary scene. This is the gory arena where ravenous bloodthirsty beasts are unleashed against the innocent. This is the gruesome scene of martyrdom and sacrifice, and yet it is the sacred altar of love and immolation where Varqa’s cherished desire was finally fulfilled.

It is not for children and the tender-hearted to listen to. But before I pause for some to leave or stop the tape, let us realize that these two heavenly doves, having weathered all kinds of turbulences, did not survive the fierce gales of this storm. With their physical wings broken, they laid down their lives as a sacrifice in the path of their Lord. Thus the silver-tongued nightingale and his prize son, Ruhu’llah, winged their flight to the apex, to the eternal skies of the world of mysteries. Now there will be a pause….

Editor’s Note:

The following is NOT for the faint of heart.

This is the ending of the story on that infamous May day, one century ago. Mirza Husayn states, “As we sat down, stunned and unable to talk, the attendants surrounded us, discussing with laughter which piece of our clothing each one would be getting tomorrow. We were so numb that we did not care. I asked one of the attendants whom we had befriended to tell us the truth about what happened behind the closed doors of that long corridor. The attendant stated, ‘As soon as the furious Hajib saw Varqa he shouted at him, “You finally did what you did.” Varqa, not knowing about the assassination, quietly answered he was unaware of having done anything wrong. Then Hajib asked Varqa, “Do you want me to kill you first, or your son?” Varqa answered, “It does not matter.” The fiend pulled his dagger, and plunged it into Varqa’s stomach, and asked him, “How are you feeling?” Unshaken and undaunted, that symbol of courage, that steadfast hero, with his last breath, exclaimed, “I feel much better than you do.” Then they fastened his head and four executioners fell upon him, severing his arms and legs piece by piece while the blood was gushing out like a fountain. Ruhu’llah, watching the dismembering of his father, was crying out, “Oh, dear father, oh dear father, take me, take me with you.” The evil Hajib walked to Ruhu’llah, and said “Do not weep. I shall take you with myself, will get you an allowance, and obtain a post for you from the king.” Ruhu’llah replied, “I do not want your allowance or the post. I wish to join my father.” Then he began to cry again.

Defied and rejected, Hajib ordered a rope to hang him, but no rope could be found. So they put Ruhu’llah’s neck in the loop of a bastinado post where usually the ankles are placed. Two attendants, one at each end of the post, lifted Ruhu’llah up until his body became limp. Then they laid his corpse on the ground. Hajibu’d- Dawlih, that bloodthirsty fiend, was not finished yet. He ordered the other two Bahá’ís to be brought. As soon as the doors to the corridor were flung open, the corpse of Ruhu’llah sprang up and fell with a thud three feet away. This terrified the evil Hajib, who ran for the door, saying he will deal with the two others the next day.

That next day was not to be, because the political plot was discovered, and the Bahá’ís were cleared. The new king, Muzaffari’d-Din Shah, was moderate and tolerant. Remember, Varqa used to read poetry in the gatherings when he was a crown prince. Now, he has the jeweled crown, and Varqa, the crown of glory.

Mirza Husayn and Haji Iman were released after a few months to recount the last months and the last hours in the lives of Varqa and his twelve-year-old son, Ruhu’llah. They left for posterity the accounts of the unshakeable constancy of the fearless poet and his son.

No doubt, you knew with certainty that Bahá’u’lláh’s promise was inevitable, but nevertheless, the manner in which they were martyred was difficult to recount and heart-wrenching to hear. Before your wounded heart cries out, “Where is justice?” permit me to read the following rendering of the history by Shoghi Effendi in God Passes By, page 83.

“Hajibu’d-Dawlih, that bloodthirsty fiend who had so strenuously hounded down so many innocent and defenseless Babis, fell in his turn a victim to the fury of the turbulent Lurs, who, after despoiling him of his property, cut his beard and forced him to eat it, saddled and bridled him and rode him before the eyes of the people, after which they inflicted under his very eyes shameful atrocities upon his women-folk and children.”

This tragic and heroic story, the complexity of which is way beyond our comprehension, will befittingly end with a pleasant and uplifting note.

Abdu’l-Baha conferred the title of Hand of the Cause on Varqa, posthumously, and the Guardian designated him as an Apostle of Bahá’u’lláh. His youngest son, Jinab-i-Valiyu’llah Varqa, became a Trustee of Huququ’llah and a Hand of the Cause during the ministry of Shoghi Effendi. After his passing, Shoghi Effendi appointed his eldest son, Dr. Ali Muhammad Varqa, as a Hand of the Cause and Trustee of Huququ’llah. As you notice, his name is after the name of his martyred and illustrious grandfather, the silver-tongued poet, Mirza Ali-Muhammad Varqa. What a unique family!

Source:

Shahrokh, K. Darius Dr.. “Windows to the Past” Bahai-Library.org: Winters, Jonah

Images:

Rúhu’lláh and his father, Varqá, in prison in Tehran shortly before their martyrdoms in 1896: Bahaikipedia.org

(c) Baha’i Chronicles