John Henry Wilcott

John Henry Wilcott

Born: December 25, 1870

Death: February 28, 1964

Place of Birth: Jay, New York

Location of Death: Hilger, Montana

Burial Location: Winifred Cemetery northeast corner of the Wilcott homestead, Hilger, Montana

John H. Wilcott started swimming the river of commitment and adversity before ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s historic trip to the west. His pioneering spanned the ministries of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, the Guardian and the Interregnum into the formation of the Universal House of Justice.

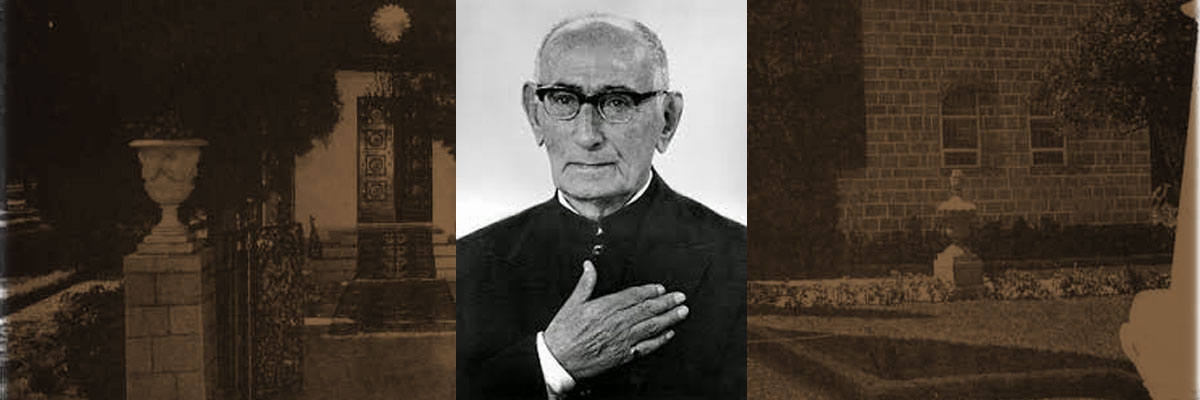

Before he was formally enrolled as a Bahá’í, he was a charter member of the Kenosha, Wisconsin Bahá’í Board of Council, a year before his formal enrollment on July 1908. John is shown in this picture of the Board of Council, probably secondfrom the right in the front row.

Before he was formally enrolled as a Bahá’í, he was a charter member of the Kenosha, Wisconsin Bahá’í Board of Council, a year before his formal enrollment on July 1908. John is shown in this picture of the Board of Council, probably secondfrom the right in the front row.

Kenosha was one of the earliest Bahá’í communities in the United States. It was not called a Spiritual Assembly until 1925. John was proud of having been a charter member. His mother, Eliza (Frazier) Wilcott embraced Bahá’u’lláh at the same time as John.

John was a member of the Temple Unity Committee, under the guidance of future Hand of the Cause Corinne True. This committee selected land for the future Bahá’í Temple in Wilmette. The committee was also busy generating enthusiasm and collecting funds for the prospective Mother Temple of the West.

John continued to contribute to the Temple Fund throughout his life. Sometimes all he had was pennies, which he gave freely. When he lived in Kenosha, he would go to that barren, but sacred plot of land in Wilmette and pray for the Temple that he never would see.

This was well before ‘Abdu’l-Bahá arrived to dedicate and consecrate that blessed spot – another major event he missed, because of his pioneering. Nor would he meet his beloved ‘Abdu’l-Bahá in this world.

Shortly after the above picture was taken, John and his mother must have left for California. While with Mrs. Goodall Cooper, Kathryn Frankland and others, a letter from ‘Abdu’l-Bahá was received by the American believers stating His desire that a Bahá’í live in every State of the United States prior to His planned visit.

The friends in California encouraged John and his mother to pioneer to Montana in obedience to the Master’s wish.

About 1909, having been associated with the Faith for just a few years, and with no experience in frontier living, they set off for Montana as Bahá’í pioneers, living in a tent when they first arrived.

Life was hard. Food was scarce and rattlesnakes were plentiful. John always carried a handgun for protection from this hazard. The Wilcotts took every opportunity to talk about the Faith. Results ranged from cynical to appreciation, but there is no record of any enrollments.

Life was hard. Food was scarce and rattlesnakes were plentiful. John always carried a handgun for protection from this hazard. The Wilcotts took every opportunity to talk about the Faith. Results ranged from cynical to appreciation, but there is no record of any enrollments.

Eliza earned a reputation as a “bush doctor” and traveled far and wide administering her herbal remedies and delivering babies. She served with her son for 10 years until her death in 1919. John was at his post for 35 years before even seeing another Bahá’í, except for his mother. His lively correspondence with believers throughout the country and commitment to pioneering kept him going.

He enjoyed his reputation as the sheepherder’s preacher, as he considered it in the same light as the Sears and Roebuck catalog being called the sheepherder’s bible. No matter how little food they had, they were always willing to share with strangers who appeared at their door.

Survival was tough. Water wells that John dug dried up and he had to go over two miles to get water and 10 miles to cut wood for cooking and heating. More than half the farmers in Montana lost their land during years of drought.

In 1918 he married Johana Schmidt who was 22 years younger. The Wilcotts had three children: Ethel (Frost) – the only one to become a Bahá’í and who pioneered to Puerto Rico; Wanda and Norman.

There is no record that Johana ever formerly enrolled in the Faith, but she expressed belief in Bahá’u’lláh. She was a great help for John, who knew little about homesteading or ranching. Johana taught him many skills needed for survival. She was also an active midwife and had a wide array of talents.

In 1924, after successive years of crop failure, John filed for bankruptcy. Rains finally came that year and John harvested his first crop in four years, staving off bankruptcy.

He was often tempted to leave, but, as his daughter Ethel said, “He obeyed everything that ‘Abdu’l-Bahá told him. He told him he must ‘stay at his post’ and nothing could drag him away.” He was truly what became known as an “‘Abdu’l-Bahá Bahá’í.”

In later years, as John’s eyesight was failing, Johana would read to him, both his ranging correspondence and the Bahá’í Writings – especially, his beloved “Gleanings from the Writings of Bahá’u’lláh”.

After 53 years at his post, in 1962, John finally got electricity and had a telephone installed so that life could be a little easier for his wife and him. He had pioneered and survived frontier life for over half a century before getting amenities, which many people cannot fathom being without.

That was also the year when Johana died, after 44 years as his companion and helpmate. John was in his 80s. With his companion and helpmate gone, he moved to Great Falls to be with his son, Norman. But he did not like city life. So, he returned to his pioneering home and homestead for his few remaining years.

Two years after Johana died, in 1964, he finally left his pioneering post for the Abhá Kingdom. He was buried on a parcel of the northeast corner of his homestead that he had given to the village of Winifred as a cemetery. He was laid to rest between the graves of his mother and his wife.

Two years after Johana died, in 1964, he finally left his pioneering post for the Abhá Kingdom. He was buried on a parcel of the northeast corner of his homestead that he had given to the village of Winifred as a cemetery. He was laid to rest between the graves of his mother and his wife.

Being an isolated believer, he did not have the support of other Bahá’ís as they gained new understandings and insights during those years of development and transition. Therefore, he seemed to have little grasp of the significance of the Guardianship, or the stupendous importance of the Universal House of Justice.

He was secure in his love for ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, service to the Cause, and steadfastness to the Covenant. Teaching to the end, he had written to Ethel that he wanted a Bahá’í funeral so others could know of the Cause. This was more than half a century of “staying at his post.”

After more than another half-century since his passing, the wind-swept log house he built was still standing – a physical symbol of his perseverance.

A lasting legacy is a Summer School named in his honor. More importantly, is the lesson of his very life in obedience and perseverance, without tangible results. He learned what ‘Abdu’l-Bahá wanted. He did it and persevered.

A lasting legacy is a Summer School named in his honor. More importantly, is the lesson of his very life in obedience and perseverance, without tangible results. He learned what ‘Abdu’l-Bahá wanted. He did it and persevered.

His life will be an inspiration for generations of dedicated Bahá’ís yet to be born.

Add Comment