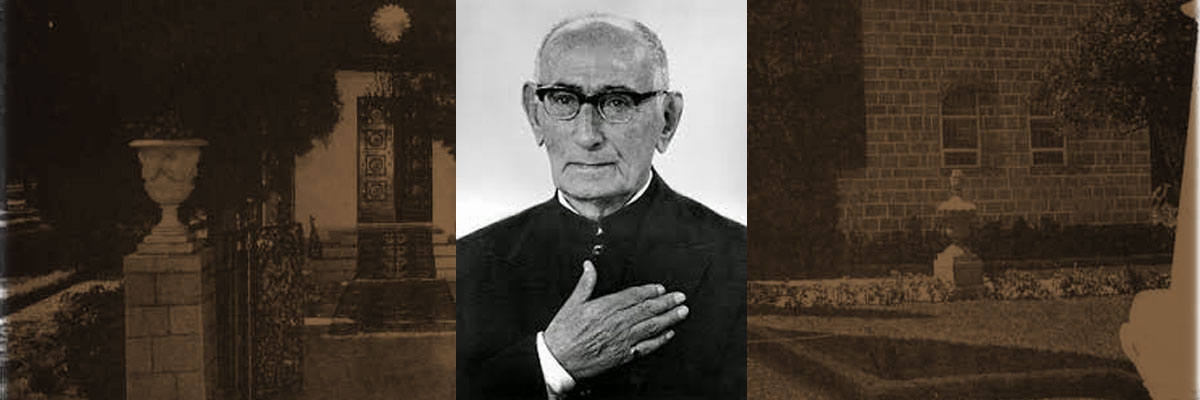

Dr. Hubert Astley St. Aubyn Parris

Dr. Hubert Astley St. Aubyn Parris

Born: August 26, 1874

Death: August 27, 1955

Place of Birth: Barbados

Location of Death: Ahoskie, North Carolina

Burial Location: Willow Oak A.M.E. Cemetery, Rich Square, Northampton County, North Carolina

A Persian poem states that, “… the wise, in crossing a river, look with their reason for a way to construct a bridge, but the foolish ones, the crazy lover throws himself into the river and crosses it without thinking about the danger.”

Dr. Parris was a champion of Bahá’u’lláh, not because he dashed off and did grand and spectacular things, or, led thousands of people into the Faith. It is because he immediately plunged into the treacherous river of service and put the spirit of this new Revelation into action. With persistence and perseverance, in isolation, without the support or company of fellow believers, abandoning the potential of a lucrative medical practice, he plunged into service to those in need of his skill, with little hope of reward. He was an embodiment of these words of Bahá’u’lláh: Blessed is he who preferreth his brother before himself. Verily, such a man is reckoned, by virtue of the Will of God, the All-Knowing, the All-Wise, with the people of Bahá who dwell in the Crimson Ark.

It was my good fortune to meet him because Beverly and I had recently become Bahá’ís and were living in Portsmouth, Virginia. I was stationed in the US Navy aboard the USS Mississippi. It was 1954 and the Area Teaching Committee asked me to find some people in remote areas whose names they had listed as Bahá’ís, but with whom they had no contact.

In those days, Apartheid was in full sway in the south. Virginia had segregated drinking fountains and waiting rooms. Even the ferry for the short ride across the river between Portsmouth and Norfolk had separate areas for white and black passengers. Burning crosses were sometimes found in front of the homes of people – white or black – who dared speak out against segregation.

One civil rights worker had a bomb thrown into his living room. Shortly before we left the area, there was a young black couple who learned of the Faith in Milwaukee and moved back to her hometown of Norfolk. They were given our name and we got together several times, but always in their home. Once, I apologized for not inviting them to our house. “Do you want a bomb in your living room?” was her simple response.

Beverly and I decided to find an apartment where we could invite our black friends. We followed up on “For Rent” ads. Only one would allow black visitors. That was in a run-down area where I was afraid to leave Beverly alone when my ship went out to sea.

The most memorable encounter was the one apartment owner who started ranting about blacks, complaining that some delivery boys even had the effrontery to “Deliva groceries rhat up to the front dooh!”

He then explained the origin of blacks by saying that after Cain slew Abel he slept with a she-ape. “That’s where they came from!” I replied: “Is that right? In the same book that mentions Cain and Abel there is a story of a flood and I don’t remember that anyone other than Noah’s family was included.”

His exquisitely irrational answer was: “Nah, Ah don’ expec’ they’d let one of ‘dem on the Ahuk.” We did not rent the apartment.

Even the US Post Offices had a window for “Colored” and a separate one for “White.” Once, Beverly was waiting in a line at the post office when a white toddler and black child each strayed from their respective lines. They were having a wonderful time playing together in the space between the two lines. The white father yanked his child back into line, away from the new playmate, and shouted out, “They don’t know how to hate. You have to teach them.”

This is the environment in which the Teaching Committee asked us to locate two people who were black. One name and address, was a woman in a black neighborhood in Richmond, Virginia.

These naïve, young, northern white folks drove100 miles from Portsmouth to segregated Richmond looking for a black woman they did not know. There was no luck. No one responded to the name at the address we had. People were walking around and I asked a woman carrying a basket of laundry if she knew the lady and how I might find her. All I got was a blank look, pleasant response, but no information.

I was, after all, an unknown white man asking black folks in the highly segregated and deeply suspicious south. Why would any of them give me useful information? They probably thought I was up to some kind of no good. It is no wonder I was unsuccessful.

The other name was Dr. Parris in Rich Square, North Carolina. Beverly was visiting her parents in Illinois, so I drove alone the 75 miles from Portsmouth to Rich Square. There was one stoplight in the middle of town. It was the only time I had seen a stoplight that gave signals in all four directions with only three bulbs. When the top light was on it would shine green two directions and red the other two. The middle light was yellow all four ways and the bottom light would reverse the directions from the top light.

There was a Texaco station at the corner, so I pulled in. There was a white man sitting on his haunches, leaning on the building, just outside the station. I asked him where I could find Dr. Parris. He chuckled as he said, “You mean ol’ doc Parris? He lives in that big green house on top of the hill.”

That is where I found a large, two-story green house, badly in need of paint, surrounded by a picket fence that must have once stood tall and proud, but not for quite some time.

A knock on the door was answered by a soft “Come in.” Opening the door, I saw a large, spare, rug-less, but spotlessly clean room, nearly devoid of furniture or pictures. In the far-right corner was a small metal-frame, single bed with a wooden chair next to it. The chair held a package of pipe tobacco, a box of matches and an ashtray piled high with burned out matches.

A small black man, propped up with pillows and holding a curved pipe, was barely visible on the bed. I was reminded of pictures I had seen of a wizened, dark-skinned Mahatma Gandhi.

“Dr. Parris?” I asked. He responded to this strange young white man who had suddenly appeared uninvited at his door in an unappealing, flat-toned voice, “If it’s money you want, I don’t have any.”

I said, “I’m a Bahá’í.” He sat up tall, his face brightened. Placing his pipe on the chair he exclaimed, “Well, you are somebody!” He nearly shouted as he patted the edge of the bed and said, “Come. Sit down. Sit down.”

Obedient to his command I sat on the edge of his bed and listened to an enthusiastic and animated telling of the time he spent at a Bahá’í Summer School. While the school’s name was never mentioned he seemed to be recalling a week at Green Acre. Details were scant, but the impact was clear.

Of a sudden he nearly leaped from his cot and led me on a tour of his home. The first stop was the dining room, just on the other side of an arch from where we had been. Again, it was a spotlessly clean room with little furniture and few pictures. There was a majestic oak dining table in the middle of the room that was clear, except for three neat stacks of magazines. The largest and most prominent was a pile of copies of the “Bahá’í News”[*]. While proudly displaying these, he mentioned the letters he had gotten from the teaching committee and how precious they were. He said he did not know why he had not answered them.

From there we went into his medical examining room. This room was filled with once important and useful medical equipment, now broken or in disrepair. The thought occurred to me that I could get my buddies from the electronics division of the USS Mississippi to help me. We could get things up and running in a day. Just as quickly I realized that fixing the malfunctioning equipment would not get his medical practice going again.

As he was explaining various features of his beloved office the picture emerged of a dedicated, small town physician whose only desire was to provide healing for any and all who were in need. Payment for services was, at best, a sometimes thing. His mission was service to the poor black people of the area, with scant thought of reward.

I also sensed the life of a man with exceptional capacity and insights, who could find few people, if any, with whom to share the innermost and important thoughts of his heart. About a year and a half after my priceless and unforgettable meeting, he winged his flight to worlds beyond where, no doubt, he was warmly welcomed by kindred souls.

Much of the life of Hubert Astley St. Aubyn Parris (1874-1955) is veiled in obscurity. What is known is that he spent a life time in service to humanity. Born in Barbados in 1874, during the first 25 years of his life he traveled to British Guyana, Britain and Ireland. He was ordained as an Anglican Priest. About the age of 26 he moved to the United States.

On several occasions he attended the “Monsalvat School for the Comparative Study of Religion” in Eliot, Maine. That may have been where he first heard of the Bahá’í Faith. He attended both the Teacher College of Columbia University, and earned a degree from Howard University.

After some years working as a minister of the Episcopal Church, at the age of 40, he earned a medical degree from Shaw University. In Wilmington, NC, served both as a medical doctor and rector of St. Mark’s Episcopal Church.

He served mankind, first as a Christian minister, then as a doctor and as member of the Bahá’í Faith in a small country town. The last 20 years of his life were spent with his medical practice in the small town of Rich Square, NC, often giving medical care free to the poor.

The Digitized records of “The Wilmington Morning Star,” mentions Parris and the Sadgwars, in 1922. It is likely that he met Louis Gregory around 1923 while living in Wilmington. He officially enrolled in the Faith in April 193010.

A project intended to find out if names on a list really represented Bahá’ís led to an unrivaled experience. Dr. Parris led me to the question of who is really a Bahá’í, and what it means to be a champion of His cause.

Being a Bahá’í: It is easy to confuse being active with being visible. In my mind there are at least two Bahá’í lists. One is in the administrative office file. Another is the one Bahá’u’lláh has. Most likely there are names on each that do not appear on the other. I know I am on the administrative list, and, hope I might also be on Bahá’u’lláh’s list.

An active Bahá’í is one for whom the teachings of Bahá’u’lláh are active in life, not just someone you see. One who, in terms of the poem at the beginning, plunges into the river of service. Dr. Parris, though rarely seen by other Bahá’ís, lived the spirit of the Faith.

In the Fire Tablet, when God is answering Bahá’u’lláh, He says, Dost Thou wail, or shall I wail? Rather shall I weep at the fewness of Thy champions…

Who are the champions? In my mind, there are five kinds of champions of Bahá’u’lláh. Some are registered as Bahá’ís and some are not. Of course, dedicated enrolled Bahá’ís are champions, when they diligently attempt to live by Bahá’í standards, do their sacrificial best to promote the current plan and obey the Institutions.

There are many who have enrolled in the Faith but, for whatever reason, don’t show up at meetings. Dr. Parris was definitely among these “invisible Bahá’ís”.

There are others who enrolled in the Faith and, for reasons of their own, resigned. These might be called “reserved troops,” they just don’t happen to be on active duty. Many of them return to the Faith and others have stepped forward at crucial moments in service of the Cause in interesting and unusual ways.

There are many defenders of the Faith from the outside. While not registered, they defend the Faith, the Bahá’ís and the teachings in a manner that may not be possible, or as convincing, for an enrolled believer. Many a Moslem in Irán has been a bulwark of defense, protecting a Bahá’í spouse and children when there were authorities who would do them harm.

There are also many people who may have never heard of Bahá’u’lláh, but who are champion promotors of His most urgent teachings. They are in the vanguard of eliminating prejudice, promoting the idea of a peaceful global community, working for women’s rights, social justice, the harmony of science and religion, and so on. These priceless champions are doing much to propel the world toward Bahá’u’lláh’s vision of a new World Order. Indeed, the Lesser Peace is being brought about by many forces outside the Faith.

Big changes come from highly motivated little people doing extraordinary things when they become intoxicated with a Divine reality that is so much larger than themselves.

God-intoxicated souls, or crazy lovers, or true believers, or heroes and heroines who have answered the call of Bahá’u’lláh and arisen to serve His Faith have done phenomenal things. Without thinking about the problems and challenges involved, confronting the danger, crossing the swirling river of adversity, sometimes risking life and limb, renouncing family, if necessary, abandoning career and possessions, doing whatever it takes to serve the sacred Cause of Bahá’u’lláh.

Dr. Parris, unknown to most, was securely in the vanguard of “crazy lovers” of Bahá’u’lláh!

Source:

Kolstoe, John. “God-Intoxicated Lovers of Baha’u’llah.” Independently published. May 2019

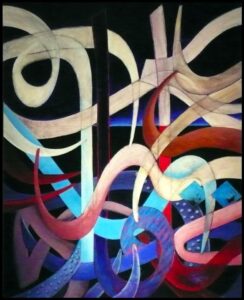

Image:

Artwork by Mehrdad Mike Iman

*The “American Bahá’í” had not yet started publication.

Add Comment