Richard Edward St. Barbe Baker

Richard Edward St. Barbe Baker

Born: October 9, 1889

Death: June 9, 1982

Place of Birth: West End, near Southampton, Hampshire, England

Location of Death: Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, Canada

Burial Location: Woodlawn Cemetery, Saskatchewan, Canada

Richard St. Barbe Baker, one of the foremost world famous environmentalists of the twentieth century, an ecologist, conservationist, forester, vegetarian, horseman, apiarist, author of some thirty books and numerous articles and a committed Bahá’í who rendered service to the Bahá’í Faith for more than fifty years.

Descended from a family that included clergy members and dedicated tree planters, St. Barbe, as he was known, was the eldest of five offspring of Charlotte (Purrott) and John Richard St. Barbe Baker, a horticulturist who raised trees and developed two popular apple varieties. As a child and youth, St. Barbe was exposed to rigorous theological debate, worked in his father’s nursery, and practiced vegetarianism, as had some of his forebears. He traced his deep love of trees to a transcendent experience: his first walk alone in the woods, at the age of five or six, which he likened to a “woodland rebirth.”

After completing his secondary education at Dean Close School, a boarding school in Cheltenham, Baker set out on his “first real adventure.” According to his own account, since childhood he had been captivated by stories about bears in letters written by a great-uncle, Richard Baker, who had been a settler in Canada a century earlier. Experiences during his teen years deepened his attraction to Canada. With his family’s consent, although initially his decision had been a “blow” to them, he left for Saskatchewan in 1909.

While plowing the prairie and working as a lumberjack near Prince Albert, he became concerned about the wasteful use of timber resources and the destructive prairie farming practices that created dust-bowl conditions through loss of topsoil. At this point, he later recalled, his commitment to conservation began. He attributed its quickening to the influence of the Cree, First Nations people who lived with and felt a part of the forests.

With the intention of assisting in strengthening the Christian congregations of homestead settlers, Baker enrolled in Emmanuel College, the divinity school at the newly established University of Saskatchewan in Saskatoon, joining the university’s second class in 1910–11. In 1913, after almost four years in Canada, he returned to England and embarked on a divinity degree at Ridley Hall, Cambridge.

A year later, shortly before the outbreak of the First World War, Baker enlisted in King Edward’s Horse, a cavalry regiment of the British Army. Later he was commissioned as an officer in the Royal Horse and Field Artillery. He went to France in 1915, was severely wounded in battle three times, and was decorated with the Military Cross. On one occasion he would have died had it not been for the alertness of a member of the burial party, who noticed, when removing Baker’s ID tag, that the “corpse” was bleeding. He was invalided out of military service in April 1918 and spent some months recovering from his injuries before resuming his interrupted studies.

Having decided to pursue a diploma in forestry, in January 1919 Baker returned to Cambridge, this time to Gonville and Caius College. His goal after receiving his degree in 1920 was to work in the field of forest protection in the British colonies in Africa. Once again he followed trails blazed by a Baker relative, in this case the famous explorer and naturalist Sir Samuel Baker, known for discovering the source of the Nile in 1864.

Kenya and the Men of the Trees:

In November 1920 the Colonial Office appointed Baker Assistant Conservator of Forests in Kenya. In this post he was responsible for identifying wood that might be sold on the British market to the advantage of the colony and for assuring that future supplies of wood would be available. This necessitated planting treated seeds and transplanting seedlings.

In November 1920 the Colonial Office appointed Baker Assistant Conservator of Forests in Kenya. In this post he was responsible for identifying wood that might be sold on the British market to the advantage of the colony and for assuring that future supplies of wood would be available. This necessitated planting treated seeds and transplanting seedlings.

In Kenya Baker witnessed the environmental devastation that resulted from the traditional slash-and-burn farming methods of the region, from overgrazing by goats, and from the colonial farmers’ introduction of crops and methods requiring enormous acreage. He developed a plan to restore the native forest by planting food crops between rows of young trees. As several crops could be harvested before the trees required transplanting, Baker hoped to demonstrate that crop growing was compatible with managing forests. The project required thousands of seedlings. With few resources and little departmental funding, he turned to the indigenous people for assistance.

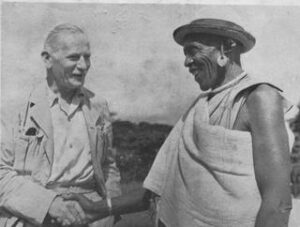

In 1922, Baker held meetings with Kikuyu chiefs and elders to urge them to counter their destructive farming methods by planting trees. Supported by Chief Josiah Njonjo and inspired by the ceremonial dances that the local people used to mark all occasions, Baker devised a ceremonial tree-planting dance to encourage the young village men to plant trees to replace the lost forests and to inaugurate his crop-and-tree scheme. He called for volunteers to join together to become Watu wa Miti (Men of the Trees).

Baker’s efforts reflected an uncommon attitude by a colonial officer toward the indigenous people:

To be in a better position to help them I studied their language, their folklore and tribal customs, and was initiated into their secret society, an ancient institution which safeguarded the history of the past which was handed down by word of mouth through its members.

Soon I came to understand and love these people and wanted to be of service to them. They called me “Bwana M‘Kubwa,” meaning “Big Master,” but I said, “I am your M‘tumwe” (slave).

Now an accepted practice termed social forestry, Baker’s approach caused the colonists to accuse him of becoming too involved with the Africans. An event that provided further evidence of his concern for the local people prevented him from rising high in the ranks of the Colonial Office. When a superior officer tried to strike a native worker with the butt of his rifle, Baker, believing the action to be unjust, intercepted the blow, taking it on his shoulder. This act, which the officer interpreted as gross insubordination, was remembered long afterward by those who had routinely experienced colonial discrimination.

Fifty Kikuyu warriors participated in the first dance of the trees on July 22, 1922. From this small beginning, the Men of the Trees organization, which Baker formally founded in England in 1924, spread to many other countries. Now known in many countries as the International Tree Foundation, it has a large membership of women and men from all walks of life. In 1978 Charles, Prince of Wales, became the society’s patron.

Introduction to the Bahá’í Faith:

Baker left Kenya in 1924, returning for a brief time to England. In the autumn he read a paper on Kikuyu beliefs at the conference “Some Living Religions within the British Empire” held in London from September 22 to October 3, 1924. At the end of his talk, Claudia S. Coles, an American living in London who was one of a number of Bahá’ís attending the conference, approached him and told him about the Bahá’í Faith. Ten days later, he sailed to Nigeria with a supply of Bahá’í books provided by Coles. He studied them during the voyage and became a Bahá’í soon after. Coles and Baker remained close friends until her death in 1931. She became, according to Baker, “one of the most active members of the Council of the Men of the Trees, which shortly after this was started in London,” and he credited her as being “a great inspiration” in his life.

Nigeria and Palestine:

From 1924 until 1929 Baker served as Assistant Conservator of Forests for the southern provinces of Nigeria. In 1929 the High Commissioner of Palestine, Sir John Chancellor, asked Baker to apply the lessons he had learned in Kenya to the Protectorate, which was suffering from the encroachment of the desert. Chancellor believed that the problem could be tackled only by securing the agreement of the different religions and interests in Palestine to take collective action. Having resigned from the forestry service to devote full time to the Men of the Trees, Baker agreed to undertake the task. He approached Shoghi Effendi, who enrolled as the first life member of the Men of the Trees, and, with the encouragement of the retired soldier and administrator Field Marshall Viscount Allenby and the explorer and geographer Sir Francis Younghusband, Baker then went on to enlist the support of the chancellor of the Hebrew University, the grand mufti of the Supreme Muslim Council, the Latin patriarch of Jerusalem, the bishop of Jerusalem, and others.

This initiative among the religious leaders of Palestine led to the creation of forty-two nurseries. Baker also helped to establish Tu Bi’Shvat, the traditional Jewish New Year of the Trees, as a national tree-planting day.

Further International Achievements:

In the 1930s extensive lumber operations threatened the groves of ancient, enormous redwood trees in California. Although small groves were to be retained, Baker believed that much larger groves were required to sustain the climate necessary for preserving the species. He launched a “Save the Redwoods” project, eventually attracting donations of more than ten million dollars. With these funds the project bought a natural reserve of some 4,850 hectares (12,000 acres) of redwoods and handed it over to the state of California to be preserved forever. In the 1960s Baker intervened again to save redwoods being threatened by the construction of a new highway; he suggested an alternate route that United States Secretary of the Interior Stewart Udall agreed to adopt.

Baker’s friendship with President Franklin D. Roosevelt contributed to his establishing the Civilian Conservation Corps as part of the New Deal initiative. From 1933 to 1942 the CCC employed more than three million people. The popular program was responsible for planting some three billion trees in all of the states and several territories of the United States; it also worked on preventing soil erosion, developing parks, and other conservation projects.

In 1945 Baker founded the World Forestry Charter Gatherings. These were annual luncheons at which representatives of as many as sixty-two national governments and other influential persons were apprised of the current situation of the world’s forests. For many years Baker opened the gathering by reading a short official message from Shoghi Effendi. In the 1970s, with more formal international meetings in place, the gatherings were discontinued for some time. On December 15, 1989 the Bahá’í International Community, in collaboration with other organizations, reconvened the annual gathering to mark the centenary of Baker’s birth. A second gathering, held on July 28, 1994 at St. James Palace in London, followed up on forestry issues raised at the 1992 Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro.

In 1952–53 Baker led the first Sahara University Expedition. Covering some 14,500 kilometers (9,000 miles) of desert from Algiers to Mount Kilimanjaro, this was an ecological survey designed to discover the speed of the desert’s advance, to develop methods of stopping the encroachment, and to consider the possibility of reclaiming the desert. Baker was convinced that the encroachment could be arrested and reclamation undertaken if appropriate measures were adopted quickly. He recommended planting a “Green Front” of trees 6,400 kilometers long (4,000 miles) and 48 kilometers (30 miles) wide along the southern reaches of the Sahara. In Kenya he met again with Chief Ngongo and others who had been present at the beginning of the Men of the Trees movement.

In 1959 Baker went to India, where he assisted Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru in instituting a tree-planting program to address the Indian desert problem and to raise the water table. He made similar efforts in Pakistan, Australia, and other countries affected by encroaching deserts.

Baker returned to the Sahara in 1964, leading an expedition through more than forty thousand kilometers (twenty-five thousand miles) of desert—by land, air, and water. His team visited twenty-four countries and met with many heads of state to urge immediate action to halt the desert’s advance. Recognizing that “The conquest of the desert will have to start with the conquest of the desert of the heart of man,” he saw Sahara reclamation as “one of the biggest tasks” humanity has ever faced: “Not in my time, but some day, there may be farms on those wastes; orchards, gardens and great cities and communities of men and women. Under the sands, nature has secreted its reserves; they must be freed for the benefit of mankind. We have the knowledge; we must find the means.” The challenge, in his view, was “not to Africa alone but to the world”; he envisioned financing Sahara reclamation by diverting “military and other personnel and… funds from the more than 120 billion dollars spent yearly on armaments.” While his recommendations have not been enacted, in recent years governments and international agencies have begun to address the question of the spreading deserts.

Baker’s international travels enabled him to lecture widely. His writings were equally extensive. Throughout his career, he published articles (some written for Bahá’í publications) and books, often including his own excellent photographs, on trees and forests, his work in various countries, and the challenges of conservation. His writings were imbued with his sense of “inward kinship with the earth and all living things.”7 Some of his writings have been anthologized since his death.

Baker’s international travels enabled him to lecture widely. His writings were equally extensive. Throughout his career, he published articles (some written for Bahá’í publications) and books, often including his own excellent photographs, on trees and forests, his work in various countries, and the challenges of conservation. His writings were imbued with his sense of “inward kinship with the earth and all living things.”7 Some of his writings have been anthologized since his death.

New Zealand:

Baker first visited New Zealand in 1931, and he returned a number of times over the following decades. After one of these visits, he wrote a book, published in 1956, entitled Land of Tané. In 1957, following a life-threatening illness, he went to New Zealand to recover, staying for a time at Mount Cook Station, a large, high-country sheep farm near Aoraki/Mount Cook, New Zealand’s highest mountain, on the South Island. In 1959 he officially transferred his residence to New Zealand when he married Catriona Burnett, whose family owned Mount Cook Station. This was Baker’s second marriage, his first having ended in divorce in 1953. He and Doreen Whitworth Long of Dorset, who had worked as his secretary in the Men of the Trees organization, married in January 1946 and had two children: Angela, born in 1946, who followed her father to New Zealand and was the only member of his family to become a Bahá’í, and Paul, born in 1949, who remained in England.

Some two hundred guests attended the October 7, 1959 Burnett-Baker wedding, and newspaper accounts in the international press reported that the couple requested trees as wedding presents. Catriona’s heavy responsibilities at Mount Cook Station hindered her from joining her husband in his international travels, but she warmly welcomed visits by his friends and provided him with moral support and a home that served in many ways as a sanctuary throughout the final twenty-three years of his life.

In New Zealand Baker was instrumental in establishing tree shelterbelts in the farming and fruit-growing area of Central Otago on the South Island, a feat that others had said was not possible. He advised many of the country’s farming and forestry leaders on how best to halt the soil erosion that had been caused by felling native trees and by over-intensive stock grazing. His close association with Sir Francis Dillon Bell and Sir Eruera Tirikatene, government ministers responsible for the Ministry of Lands and Forests at different times, meant he was a major influence on the development of policies in New Zealand that protected native forests and increased agricultural and farming productivity through reforestation.

In 1962, at the age of seventy-three, Baker embarked on a five-month, nineteen-hundred-kilometer journey (twelve hundred miles) on horseback from the northernmost kauri—a giant native tree whose trunks he likened to the columns of “an ancient Greek temple” at Cape Reinga on the North Island to the southernmost kauri at the bottom of the South Island. As he made his way south, Baker visited many schools, talking about the importance of trees to thousands of schoolchildren. The ride, highlighting the United Nations’ Freedom from Hunger Campaign, received much media coverage.

Bahá’í Activities:

Shoghi Effendi referred to Baker as “the first member of the English gentry to join the Bahá’í Faith.” Over the next six decades, Baker remained a steadfast Bahá’í, rendering notable services and assisting with the work of the Bahá’í Faith as his own professional commitments and travels permitted. In 1944, for example, he was a member of the committee in the United Kingdom that organized the Bahá’í Faith’s first centenary, and during the early 1950s “he was a regular participant at every Bahá’í Summer School” in the United Kingdom. Following his 1952–53 Sahara expedition, Baker attended and spoke at an international Bahá’í conference in Kampala, Uganda, February 12–18, 1953.

After Baker moved his home base to New Zealand in 1959, he gave many talks throughout the country at meetings organized by local Bahá’ís. Whenever the opportunity arose, he was always willing to travel from his somewhat isolated South Island home to promote the Bahá’í teachings.

In the 1970s Baker provided advice about tree planting on the site of the future Bahá’í House of Worship in Iran, carrying with him on his flight to Tehran hundreds of young redwood trees from California and staying for a time to supervise “the development a special nursery” for the trees. He also advised on tree planting at various sites at the Bahá’í World Center in Israel.

The Man of the Trees:

Baker was an inspirational figure whose blend of environmental awareness, spiritual activism, and personal charisma made him unique. Well ahead of his time, he was responsible for planting billions of trees and was fearless in his promotion of the need for humanity to respect nature and to be the stewards of God’s earth. His good works can be seen in all continents.

“Richard St. Barbe Baker was a man for all seasons,” Dr. Keith D. Suter, president of the United Nations Association of Australia, wrote in tribute. “He was an internationalist. . . . he was able for well over half a century to cross frontiers between nations which were often at political odds with one another, such as the United States and Soviet Union. He looked upon the world as his garden.” “St Barbe, as he was affectionately known to many, was,” according to Richard Burleigh’s assessment in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, a practical man of exceptional vitality, motivated by an unwavering belief in the need to reverse the destruction that had been wrought from the earliest times upon the forests of this planet. The combination of his ideals, backed by his religious convictions and blended with his agreeable personality, his ability to relate constructively to everyone he encountered, and his tireless energy, culminated in the vast contribution he made to pioneering the saving of the world’s forests. He was always the first to declare that what had been achieved was the outcome of teamwork, but there can be no doubt that he was the indispensable catalyst.

Baker had audiences with many world leaders and dignitaries: members of royalty, government officials, and religious leaders, including two popes. On such occasions he would often quote from the Bahá’í writings in a subtle and dignified manner. In his lifetime Baker received a number of awards, medals, and honors. On November 6, 1971 the University of Saskatchewan conferred on him the honorary degree of Doctor of Laws. In 1978 Queen Elizabeth II appointed him an OBE (Officer of the Order of the British Empire).

Baker died on June 9, 1982 during a visit to Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, only a few days after planting, on the grounds of his alma mater, his last tree. At the time of his death, he was working on yet another book. Following a Bahá’í service, he was buried near two large spruce trees in Woodlawn Cemetery, Saskatoon. The Universal House of Justice cabled on June 10, 1982: “passing distinguished dedicated servant humanity richard st barbe baker loss to entire world and to bahai community an outstanding servant spokesman faith. His devotion beloved guardian [Shoghi Effendi] never ceasing efforts best interests mankind meritorious example.”

A celebration of Baker’s life and work was held at St. John’s Church, London, on July 14, 1982. A conference inaugurating the Richard St. Barbe Baker Foundation took place at the University of Saskatchewan on June 4–5, 1984, and in 1985 the foundation presented its first Man of the Trees Award to Chinese forestry ecologist Zhu Zhaohua. On March 28, 2003 the Borough Council of his birthplace, West End, Hampshire, unveiled a bronze bas-relief memorial in honor of the village’s illustrious son.

Source:

Momen, Wendi and Voykovic, Anthony A. “Richard Edward St. Barbe Baker” Bahá’í Encyclopedia Project, bahai-encyclopedia-project.org

Images:

Baha’i World Centre Archives