Harriet Gibbs Marshall

Harriet Gibbs Marshall

Born: February 18, 1868

Place of Birth: Victoria, Canada

Date of Death: February 21, 1941

Location of Death: Washington, D.C.

Burial Location: Washington, D.C.

Harriet Aletha Gibbs was the daughter of Mifflin Wistar Gibbs, a lawyer in Little Rock, Arkansas, who became the first African-American city judge in the United States, and the former Maria Ann Alexander, a school teacher. Harriet had one sister, Ida Alexander Gibbs.[1]

In 1889, Harriet became the first African-American woman to graduate from Oberlin Conservatory with a degree in music.[1]

Most impressive among institutions established by black women was the Washington Conservatory of Music and School of Expression founded in Washington, D.C., by Harriet Gibbs Marshall.[2]

Marshall was the first of her race to graduate from the Oberlin Conservatory of Music as a piano major, and, after piano study in Europe, she concertized in the United States. She established a department of music (ca. 1890) at Eckstein-Norton, a small black college in Cane Spring, Kentucky, and raised money for the music building through her piano concerts and through performances of the Eckstein-Norton Choir, a group she organized and directed. Harriet Marshall helped to establish yet another school. During her stay in Haiti, where her husband served with the U.S. legation, she co-founded the Jean Joseph Industrial School in 1926 with Rosina J. Joseph. Washington Conservatory of Music Collection.[2]

Marshall’s most remarkable contributions, however, were made in connection with the Washington Conservatory. Her experience at Eckstein-Norton convinced her of the need to find and train talented youth and inspired Marshall to open her school in 1903. [2]

It was more widely known than other private schools owned and operated by blacks and, by offering conservatory-level instruction, attracted students mainly from Washington but also from the North, South, and Midwest. It was also the longest to survive, although not without tremendous effort on Marshall’s part. In order to keep the school financially afloat, she wrote voluminously for assistance to politicians, artists, and any others whom she considered possible donors. [2]

She became a Bahá’í in 1912, while ‘Abdu’l Bahá was visiting the US. She hosted many Baha’i events at the Conservatory. [1]

After Marshall’s death in 1941, her cousin Josephine V. Muse directed the activities of the Washington Conservatory. Although there was never a surplus of money on hand, the school continued to operate until 1960 with assistance from white as well as black philanthropists.[2]

From its beginning, the Washington Conservatory recruited a faculty of highly trained, and, in some cases, widely known musicians. Emma Azalia Hackley, whose later achievements as singer, conductor, and educator are discussed below, commuted from Philadelphia to teach at the conservatory during the 1903–4 academic year. Her response to the invitation to teach at the school was probably representative: “I would enjoy very much the association with you and other persons mentioned as the faculty-to-be. In a kind of faint far-off way, we have nursed a

somewhat similar idea here, but we are not so blessed with talent as is Washington.”[2]

Throughout her career, Marshall was fortunate in that she was encouraged by her father, Judge Wistar Mifflin Gibbs. He contributed the building in which the school was housed, and in his letters he assured her of his support for whatever decisions she made.[2]

Although she received assistance from many donors, and endorsements from prominent black musicians such as the composer Florence Price, some questioned the need for the school. Henry C. King, president of Oberlin, spoke of his initial reservations, “The question . . . was whether with the musical department of Howard University, there really was any such demand for another school [in Washington].” He did finally give Marshall his endorsement, commenting, “I am glad to send you a word that I hope may be of help to you in building up your work. You certainly seem already to have developed quite an institution.”[2]

Harriett Gibbs Marshall died in Burrell’s Private Hospital in Washington, D.C.

Source:

1 wikipedia.org

2 Ralph P. Locke and Cyrilla Barr. “Cultivating Music in America”

University of California Press: pp. 220-221

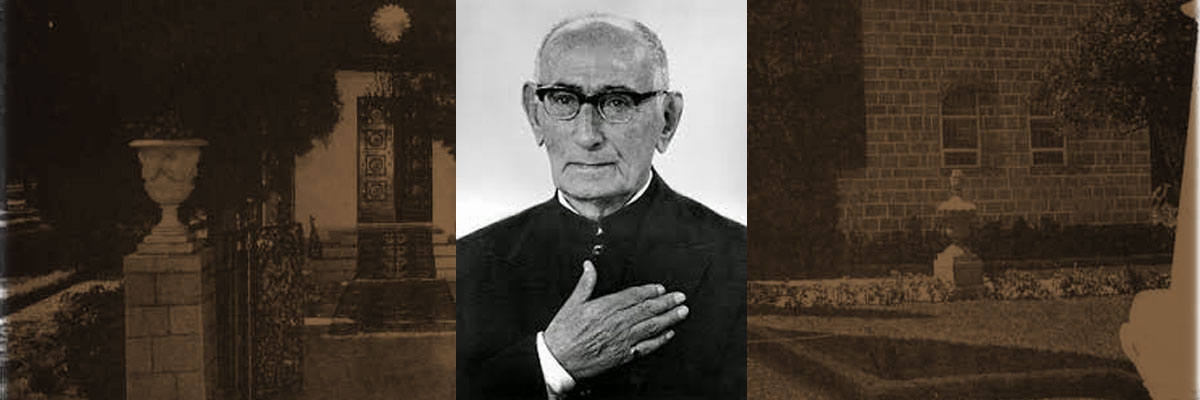

Image:

Courtesy of Howard University

Add Comment