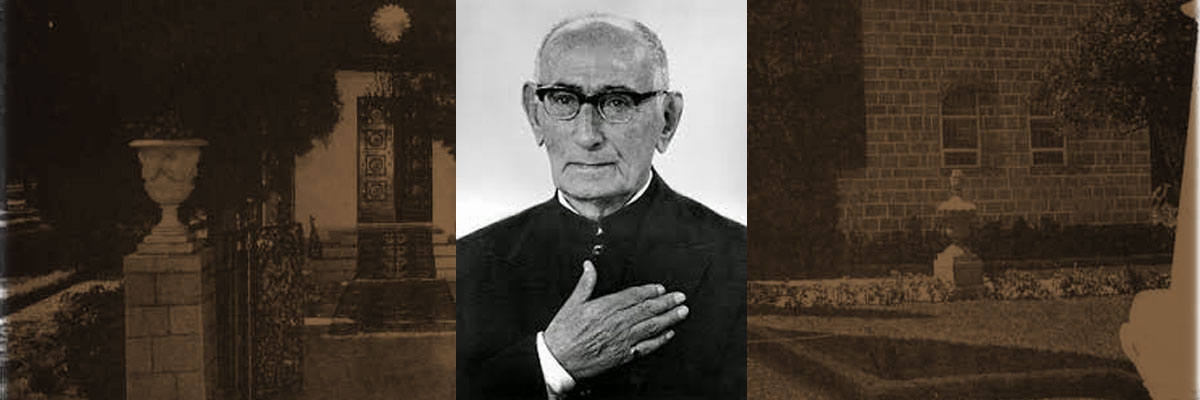

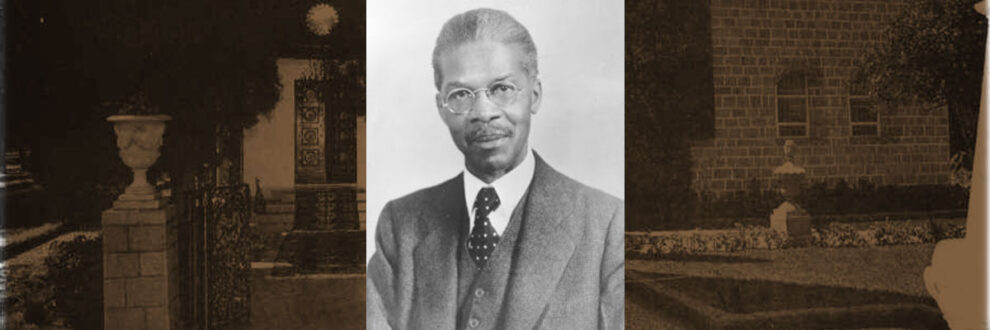

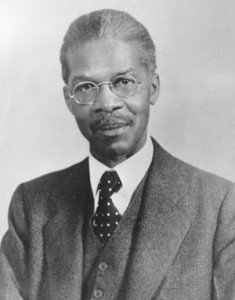

Louis George Gregory

Born: June 6, 1874

Death: July 30, 1951

Place of Birth: Charleston, South Carolina

Location of Death: Eliot, Maine

Burial Location: Mount Pleasant Cemetery, South Eliot, Maine

Louis George was born in Charleston, South Carolina, on 6 June 1874, less than a decade after his parents were freed from slavery. His mother, called Mary Elizabeth and generally known by her middle name, was the daughter of Mariah (“wholly of African blood”), a nurse on Elysian Fields plantation in Darlington, South Carolina, and the white plantation owner, George Washington Dargan. A cotton farmer, lawyer, state senator, and judge, Dargan died in 1859, at the age of fifty-six, leaving an estate that included some 119 slaves on two plantations. Mariah and Elizabeth were not sold off and separated, as often occurred when a planter’s estate was settled; they remained slaves on Elysian Fields until the end of the Civil War (1861–65), when they were emancipated.

During the first, chaotic years of freedom, Mariah’s husband, a blacksmith, prospered enough to buy a horse and a mule, but his success attracted the anger of the white supremacist Ku Klux Klan. One night, Klan members rode up to his house, called him outside, and killed him. After debating whether to “Shoot into the house and kill that woman too,” they decided against it and rode away.

Despite the unsettled postwar conditions in Darlington, Elizabeth was able to obtain a rudimentary education. While still a teenager, she married Ebenezer (E. F.) George. He is described in the 1870 census as a blacksmith and a mulatto, and noted as literate, but little else is known about him. The census indicates that the couple’s household in Darlington included their first son, Theodore Augustus, born in 1869, and Elizabeth’s mother, known in postwar records as Mary Bacot. In the early 1870s, the family moved from Darlington to Charleston. There the couple’s second son, Louis, was born.

Although the city offered opportunities for work and education, the George family experienced hard times. Ebenezer fell ill with tuberculosis, dying sometime before 1880. As an adult, Louis Gregory retained no memories of his father, but he recalled the deep poverty into which the family soon plunged.

Two major influences during Louis’s childhood were his maternal grandmother and his mother. From Mary Bacot, Louis learned to face challenges and hardships with courage, dignity, resourcefulness, and a sense of humor. Louis recalled that she would tell stories of plantation life that made him helpless with laughter. His mother, who worked as a tailor to support her family, conveyed to Louis her refined sensibilities and a love of learning.

The third major figure in Louis’s childhood was George Gregory, whom Elizabeth married on July 14, 1881. A freeborn native of Charleston from a property-holding family, a Union army veteran, a carpenter by trade, and a widower, Gregory rescued the little family from destitution, raised and educated his two stepsons, and gave them his surname. The respite from suffering was brief, however. In 1890 Louis’s brother died of typhopneumonia, and Elizabeth died of spinal meningitis just a year later. Yet George Gregory remained “a real father” to Louis and to stepchildren from a subsequent marriage, creating family ties of affection that remained strong even after his death in 1929.

Louis Gregory belonged to the first generation of African Americans in the South to have a legal right to education. He attended state-run primary schools and later studied at private institutions established by white missionaries to educate the most promising young African Americans—those who came to be known as the “talented tenth,” to use the phrase coined by W. E. B. DuBois. Gregory received his secondary education at Avery Normal Institute, the first high school for African Americans in Charleston to provide a college-preparatory curriculum. He graduated in June 1891, shortly before his mother’s death, and then attended Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee, where he earned a bachelor’s degree in 1896.

After teaching a few years at Avery, Gregory decided to become a lawyer. His choice of career required leaving the South; the region offered African Americans no opportunities to study law and, in the post-Reconstruction period, virtually no possibility of employment in the legal field. In 1899, he enrolled in the School of Law at Howard University, an historically black university in Washington DC. One of twenty graduates (all male) in 1902, he gave the commencement address, entitled “The Growth of Peace Laws,” in which he focused on disarmament and international peace initiatives. He was admitted to the bar of the District of Columbia in October 1902 and the bar of the United States Supreme Court in March 1907.

For fifteen years, Gregory practiced law in Washington—for a time in partnership with another young Howard graduate, James A. Cobb, who later became Assistant United States Attorney in Washington and a judge of the District of Columbia Municipal Court. Both men were considered rising stars in Washington’s black community. Beginning in 1904, Gregory worked for a decade as a clerk at the United States Treasury Department; he was promoted several times before returning to full-time private practice.

Disillusioned by the mistreatment of African Americans in the post-Reconstruction period, Gregory felt compelled to protest racial segregation and the infringement of civil rights. His ideas, as he later described them, were “radical,” and he was committed to a “program of fiery agitation.” Although his mother and grandmother had been deeply religious, religion was no longer of any interest to him; he “had been seeking,” he recalled many years later, “but not finding truth, had given up.” He first heard about the Bahá’í Faith from a Treasury Department coworker—a white southerner who, although not seriously interested in the religion for himself, thought Gregory would be. Gregory had no inclination to attend a religious meeting, but finally, late in 1907, he acquiesced to his friend’s prodding. Pauline Hannen, also a white southerner, welcomed him to the meeting with unusual warmth, telling him that what he was about to hear would make possible “a work . . . that would bless humanity.” The talk by Lua Getsinger, one of the first Western Bahá’ís, provided a “brief but vivid” historical account of the religions of the Báb and Bahá’u’lláh.

Confounding his own expectations, Gregory was intrigued and accepted Pauline Hannen’s invitation to study the religion. She and her husband, Joseph, became his teachers and close friends. For the next year and a half, he attended meetings in their home, impressed by their freedom from racial prejudice, attracted by their beliefs, yet held back by his agnosticism. Finally, the Hannens pierced his “mental veils” by teaching him “how to pray.”

Gregory became a Bahá’í in June 1909. “It comes to me,” he wrote the Hannens a month later, “that I have never taken occasion to thank you specifically for all your kindness and patience, which finally culminated in my acceptance of the great truths of the Bahá’í Revelation. It has given me an entirely new conception of Christianity and of all religion, and with it my whole nature seems changed for the better. . . . It is a sane and practical religion, which meets all the varying needs of life, and I hope I shall ever regard it as a priceless possession.”

Gregory believed that, in embracing the new faith, he neither set aside his commitment to racial equality and social justice nor distanced himself from those working for change. Instead, he refocused his undiminished concern for the welfare of his people by placing it within a universal context: the establishment of a world order encompassing all peoples, founded on faith in a Supreme Being and an ennobling vision of human destiny.

One of Louis Gregory’s first actions as a Bahá’í was to confront de facto segregation in the Washington DC Bahá’í community. Rather than being disaffected by the disparity between the Bahá’ís’ professed beliefs and their actions, which largely reflected customary social attitudes and practices, Gregory became an agent of change. His mission was reinforced by ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, who wrote in 1909 in reply to Gregory’s first letter to Him, “I hope that thou mayest become . . . the means whereby the white and colored people shall close their eyes to racial differences and behold the reality of humanity.” Gregory’s dedication to promoting the pivotal principle of the Bahá’í Faith, the oneness of humankind, was thus rooted in his life experience and temperament and confirmed by his relationship with ‘Abdu’l-Bahá.

In early 1911 Gregory became the first African American Bahá’í to have the privilege of pilgrimage at ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s express invitation. He traveled to Egypt, where ‘Abdu’l-Bahá was residing at the time, and then visited the Bahá’í holy places in Ottoman Palestine. The pilgrimage not only had a profoundly transformative spiritual impact on Gregory but provided opportunities for ‘Abdu’l-Bahá to stress the vital importance of bringing black and white Americans together. “‘Abdu’l-Bahá said many wonderful things during my brief contact with him in Egypt, which lasted less than a fortnight,” Gregory later recalled. “But more than anything else his discourse was about the American race problem.” When Gregory asked ‘Abdu’l-Bahá for His guidance, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá reiterated the wish He had expressed in His first letter to Gregory, urging him to “Work for unity and harmony between the races.”

The close association between Gregory and ‘Abdu’l-Bahá continued during ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s visit to North America, April 11 – December 5, 1912. Gregory was instrumental in arranging for two major speaking engagements for ‘Abdu’l-Bahá in Washington DC on April23: at noon to an audience of more than a thousand in Rankin Chapel at Howard University, and that evening to a large gathering of the Bethel Literary and Historical Association at the Metropolitan African Methodist Episcopal Church. That same day, Ali Kuli Khan, chargé d’affaires of the Persian Legation, and Madame Florence Breed Khan, both Bahá’ís, held a luncheon and a reception in ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s honor. At the luncheon, to which about fifteen socially prominent guests had been invited, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá defied both Washington protocol and the conventions of racial segregation by insisting that Gregory join Him and by adding a place for Gregory immediately to His right, in the seat of honor. Seven months later, during ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s second visit to Washington, the Bahá’ís organized a banquet at Rauscher’s Hall that was attended by some three hundred people. It was the first interracial social event ever held by the Bahá’ís in the nation’s capital city.

In further defiance of convention, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá encouraged the marriage of Gregory and a white English Bahá’í, Louisa (Louise) A. M. Mathew, whose pilgrimage in 1911 had coincided with Gregory’s and who had traveled to America with ‘Abdu’l-Bahá at His invitation. Although ‘Abdu’l-Bahá had raised the topic of intermarriage during their visit to Egypt, telling Gregory, “If you have any influence to get the races to intermarry, it will be very valuable,” at first they thought of each other only as friends. When they met again in America, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá urged them to consider their relationship in a new light. Only then did the potential attachment He had sensed between them blossom into love. They were married in a quiet ceremony in New York City on September 27, 1912, becoming the first interracial Bahá’í couple at a time when intermarriage in the United States defied popular scientific theories about the baneful effects of “race mixing,” flouted the customary dictates of a divided society, and was a criminal offense in much of the nation.

‘Abdu’l-Bahá described the Gregorys as “an introduction to the accomplishment” of fellowship between the races. Although the couple had no children of their own, they enriched the lives of many young people and, over the years, became a particular source of strength to a growing number of interracially married couples among the American Bahá’ís.

Besides setting an example of courage in his own personal life, Gregory worked in three separate but interrelated fields to promote the oneness of humankind. First, he devoted himself to teaching the Bahá’í Faith, particularly among African Americans. His efforts in Washington DC immediately attracted the interest of a number of professionals and intellectuals. The need to accommodate them spurred the Washington Bahá’ís to begin reconsidering practices based on racial prejudice and to commence the long, spasmodic process of rooting out those prejudices. Although it would be many years before the community overcame overt racial barriers, Louis Gregory’s activities as a new Bahá’í led to the holding of some integrated meetings, paving the way for many interracial gatherings during ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s visit.

On teaching trips to the South in 1910 and 1915, Gregory found African Americans to be “deeply and vitally interested” in the Bahá’í message. As a southerner and a graduate of Avery, Fisk, and Howard, a recognized member of the African American intelligentsia, and an eloquent speaker, he was welcomed as a lecturer at numerous black schools and colleges, churches, and social organizations in the South.

In 1916, when the North American Bahá’ís received the first five letters of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s Divine Plan, summoning them to disseminate the Bahá’í Faith throughout the continent and the world, Gregory responded to ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s call to establish the Faith in the southern states. Traveling extensively for about six weeks in the fall of 1916, Gregory spoke to an estimated fifteen thousand people. He returned to Washington determined to free himself for more travel. With Louise’s full agreement—even though she was seldom able to travel with him because of the constraints of a racially divided society—he closed his law practice and a real estate firm he had just established and turned down a position on the law faculty at Howard University.

Gregory’s journeys continued for the next thirty years. Although he concentrated primarily on the South, he visited forty-six states as well as parts of Canada. Gradually, a pattern evolved: he would travel during the winter, sometimes interrupted by weeks or months devoted to administrative and organizational activity in the North, and spend summers, if possible, with Louise. At first their home base continued to be Washington DC. Later they lived in New England: in greater Boston; Portsmouth, New Hampshire; and Eliot, Maine. They especially enjoyed participating in summer classes and conferences at Green Acre Bahá’í School in Eliot, where their activities provided a respite from the periods of “enforced separation” that Louis’s work entailed.

After making the decision to give up his law practice, Louis and Louise Gregory paid for his travels with their personal resources, including the proceeds from the sale of the home that served as their refuge from discrimination. After their funds were depleted, he accepted financial assistance from friends and, for more than a decade, a monthly subsidy from the Bahá’í fund, a necessity with which he was never comfortable. The termination of that subsidy in January 1933, during the depths of the Great Depression, tested him personally for a time but did not deter him from the work to which he had long been completely committed.

For nearly three decades, from 1917 until 1946, he persevered as an itinerant Bahá’í teacher despite meager means and difficult, degrading traveling conditions. Particularly in the South, where transport was segregated and public accommodations for African Americans were virtually nonexistent, Louis Gregory spent countless hours sitting on hot, dirty trains and often, having arrived in a new town, seeking a bed for the night.

Noteworthy among Gregory’s journeys was a 1921 coast-to-coast trip, the longest he ever made, described by a Bahá’í administrator at the time as an achievement unsurpassed in the history of the North American Bahá’í community. In 1933, he participated in one of the first interracial teaching trips to the South. In the mid-1930s he responded to a call by Shoghi Effendi for intensive teaching; Gregory stayed in Nashville, Tennessee, until there were enough Bahá’ís to form its first local administrative body.

Beginning in 1922, rather than remaining at home while her husband traveled, Louise Gregory began spending increasingly lengthy periods of time in Europe, where she supported herself by teaching music, English, and Esperanto and helped form Bahá’í communities in a number of countries, including Bulgaria and Yugoslavia. Shortly after Louise returned from the Balkans in 1936, the Gregorys responded to a new call by Shoghi Effendi to establish the Bahá’í Faith in every country of the Americas. They sailed for Haiti in January 1937, planning to spend at least three months, with the intention of returning or remaining indefinitely. They were immediately successful in attracting the nucleus of a Bahá’í community but then encountered government opposition. In April 1937 they sailed for New York, hopeful that the official attitude would change and allow them to return.

That year marked the beginning of the Seven Year Plan, the first of several plans devised by Shoghi Effendi for the expansion of the Bahá’í Faith within the framework of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s Divine Plan. With doors in Haiti having shut, Louis Gregory resumed speaking tours throughout the United States but also focused on building Bahá’í communities in the six states in the South that had no resident Bahá’ís when the plan was devised. During the winter of 1937–38, he spent several months at Tuskegee Institute, an historically black institution of higher education in Tuskegee, Alabama. In January 1939 he went to Pine Bluff, Arkansas, the location of another historically black college, and remained for a month of intensive activity. Over the next several years, even though World War II made traveling difficult, he visited numerous college campuses in the South, white and black alike, as well as in border states and the Midwest.

The pace of Gregory’s journeys remained brisk until 1946, when his own brief illness combined with Louise’s increasing frailty led him to curtail his travels as well as his administrative work. The couple settled into quiet retirement in Eliot, near the Green Acre campus. There they enjoyed gardening and the simple domestic pursuits that their life together had seldom allowed.

Louis Gregory made signal contributions not only to teaching the Bahá’í Faith but also to a second field of activity: Bahá’í administration. He was first elected in February 1911 to fill a vacancy on the Working Committee, the embryonic Bahá’í administrative body in Washington DC. In 1912, during the national Bahá’í convention attended by ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, Gregory was elected to the Executive Board of Baha’i Temple Unity, the governing body in North America at the time.

Gregory’s effectiveness as an administrator kept him in the forefront of national administrative service for more than three decades. In 1918 he was again elected to the Executive Board of Baha’i Temple Unity and in 1922 to the National Spiritual Assembly of the Bahá’ís of the United States and Canada, which superseded the Executive Board. One of few African Americans elected to national leadership in any interracial organization in the first half of the twentieth century, he served on the National Assembly for fourteen years: 1922–24, 1927–32, and 1939–46. Several times he received the highest or second highest number of votes cast. He filled a number of administrative roles on the Assembly, becoming its first recording secretary, an office he held for six years, and helping to draft its bylaws, which became the model for the charters of all National Spiritual Assemblies throughout the world. He also devoted energy to the work of a national Bahá’í interracial committee, which he served as a member and an officer for many years.

Gregory attended almost every national Bahá’í convention from 1911 until his retirement in 1946. Often he was elected convention secretary, served as convention reporter, or addressed the gathering as a featured speaker.

In addition to achieving distinction as a Bahá’í teacher and administrator, Louis Gregory served as a standard-bearer in a third field: the promotion of race unity. Both ‘Abdu’l-Bahá and Shoghi Effendi repeatedly called the attention of the American Bahá’ís to the importance of confronting racial prejudice, which Shoghi Effendi described as America’s “most vital and challenging issue.” Gregory led the community’s response. Guided by ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s instruction to work for amity and harmony between the races, Gregory learned many valuable lessons while tackling challenges in Washington DC. Later, encouraged in his work by Shoghi Effendi, Gregory’s activities became national in scope; for decades he was the preeminent Bahá’í writer, lecturer, and organizer on this theme.

In the North, conferences and other activities sponsored or cosponsored by the Bahá’ís resulted in a significant public role for the religion in the fields of race relations and civil rights. These events provided a platform for the exchange of views by outstanding leaders, white and black. Among them were W. E. B. DuBois, A. Philip Randolph, William Stanley Braithwaite, Franz Boas, James Weldon Johnson, Jane Addams, and Roy Wilkins, to name a few who were not Bahá’ís, and distinguished Bahá’ís such as Alain Locke, Dorothy Baker, Matthew Bullock, Sarah Martin Pereira, and Horace Holley. Gregory frequently served behind the scenes as organizer or publicist and sometimes took a more visible role as chairperson or speaker.

In the South, Gregory often attempted to overcome racial barriers, directly and indirectly. He spoke to racially mixed audiences on a number of occasions and at times to white groups, including the student bodies of white colleges. He once shared a platform with a grand cyclops of the Ku Klux Klan. Simply by associating with white Bahá’ís, especially women, he risked arrest or even lynching; yet he was undeterred.

Once, while visiting Miami, he and two white women from the North arranged for twenty-one Bahá’í meetings in a fortnight, attracting people of both races. At the end of his stay, the three took time off for a little sightseeing and a picnic on a beach that happened to be in the white section of town. Afterward, a friend asked him whether he realized that all the African Americans were praying for him because, not being from the area, he obviously failed to realize how dangerous it was to be seen with white women. Gregory replied that, having been born and reared in the South, he knew its customs well (“about as well as “Brer Rabbit in the briar patch”) but found his protection in God: “If He does not hold me I am unsafe anywhere.”

Under the difficult and dangerous conditions that characterized a prejudiced and racially segregated society, the American Bahá’í community in its first half century struggled to exemplify its stated belief in oneness. It experienced spurts of systematic progress, aroused by stirring calls to action from ‘’Abdu’l-Bahá and Shoghi Effendi, followed by periods of retrenchment and apathy. Throughout, Gregory led the way, demonstrating forbearance, dignity, and unshakable faith and vision.

In 1932, for example, as secretary of the National Bahá’í Committee for Racial Amity, Gregory responded to a Local Spiritual Assembly that had instructed one of the members of its community to channel her enthusiasm for promoting racial amity into holding a study class “for colored people” in her home. He cautioned the Assembly to reconsider an action that would be “fore-doomed to failure,” bringing it “under fire” from both blacks and liberal whites, who would perceive it as segregation. Yet he declined to make racial attitudes a litmus test of faith. “My observation,” he wrote an African American Bahá’í friend in 1950, “is that many whites are unconscious of their prejudices and many colored people reflect, consciously or otherwise, the prejudices of the whites.” He believed that overcoming prejudice requires effort, patience, and acknowledgment of the sincerity of others, even if “their views may clash with ours,” but that the Bahá’í Faith “if adhered to will inevitably train people out of their prejudices and insularities of thought.”

Louis Gregory holds, in the words of Shoghi Effendi, a “unique position” in North American Bahá’í history. Gregory’s lifetime of effort cannot be considered separately from his attainment of extraordinary personal attributes. From his youth, Gregory was bright, multitalented, and idealistic, gifted with eloquence and a sense of humor. After becoming a Bahá’í at the age of thirty-five, he began working consciously toward personal spiritual transformation and the achievement of deep faith, patience, and humility.

A milestone in Gregory’s spiritual journey was his pilgrimage in 1911. “Verily, he has much advanced in this journey,” ‘Abdu’l-Bahá observed. “He received another life, and obtained another power. When he returned, Gregory was, quite another Gregory. He had become a new creation.” In 1920 ‘Abdu’l-Bahá paid him this tribute: “That pure soul has a heart like unto transparent water. He is like unto pure gold. This is why he is acceptable in any market and is current in every country.”

At a time when few Americans could see beyond color, many of Louis Gregory’s white contemporaries recognized him as a spiritual giant and a beacon of true humanity—a source of “shimmering radiance,” one recalled, “that was so remarkable, that seemed to be part of him.” A Bahá’í with whom Gregory traveled as part of an interracial team in the South recalled, “I never saw him show anger, impatience or resentment”; instead, when met by hostility, Gregory seemed to search “his innermost being and beyond for a solution to a change in the relationship.” Martha Root, the outstanding international Bahá’í teacher in the Faith’s first century, observed, “I always feel he is one of the greatest disciples of this new day.”

Shoghi Effendi’s letters to Louis Gregory often touch on the theme of Gregory’s spiritual distinction. In 1933, at only the midpoint of Gregory’s long years of service, Shoghi Effendi observed:

I feel impelled to . . . reaffirm my deep sense of indebtedness to you for your magnificent work in the service of the Faith of Bahá’u’lláh. No words of mine can pay adequate tribute to the spirit that glows within your breast or to the determination that fires your soul in your unique & highly meritorious endeavors. . . . You have attained spiritual heights that few indeed can claim to have scaled. You have displayed a spirit that few, if any, can equal.

The news conveyed in Gregory’s letters was, in Shoghi Effendi’s words, a source of “inspiration” and “comfort.” “I am always relieved by your letters from the burden of care & responsibility which often oppresses me,” Shoghi Effendi stated in a letter dated 29 January 1930. And again: “You hardly realize what a help you are to me in my arduous work.”

Alert and active until the end of his life, although for the last five years he no longer traveled extensively, Gregory died suddenly at home on July 30, 1951. He was buried in Eliot.

Shoghi Effendi conferred on Gregory posthumously the rank of Hand of the Cause of God, making him the eighth person and the fourth Westerner (following John Esslemont, Keith Ransom-Kehler, and Martha Root) to be so named in the period 1925–52. “Profoundly deplore grievous loss of dearly beloved, noble-minded, golden-hearted Louis Gregory,” Shoghi Effendi cabled the Bahá’ís of the United States. “Keenly feel loss of one so loved, admired and trusted by ‘Abdu’l-Bahá. Deserves rank of first Hand of the Cause of his race.”

In the United States and around the world, Louis Gregory has been recognized for his singular achievements. His old friend and former law partner, Judge James Cobb, paid tribute to him as “one of those who enriched the life of America.” Bahá’ís have named institutions and activities in his honor—among them, several schools in Africa; the Louis G. Gregory Bahá’í Institute in Hemingway, South Carolina (1972); radio station WLGI, also in Hemingway (1985); and the Louis Gregory Cottage (formerly the Arts and Crafts Building) at Green Acre. In February 2003 his boyhood home at 2 Desportes Court in Charleston was dedicated as the first museum in the city to honor a particular individual and the first Bahá’í-owned museum in the United States.

Source:

Morrison, Gayle “Louis George Gregory” Bahá’í Encyclopedia Project, bahai-encyclopedia-project.org

Images:

Baha’i World Centre Archives