Arthur Pillsbury Dodge, Disciple of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá

Arthur Pillsbury Dodge, Disciple of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá

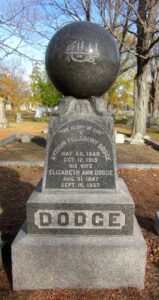

Born: May 28, 1849

Death: October 12, 1915

Place of Birth: Enfield, New Hampshire

Location of Death: Freeport, New York

Burial Location: Lakeside Cemetery, Wakefield, Massachusetts

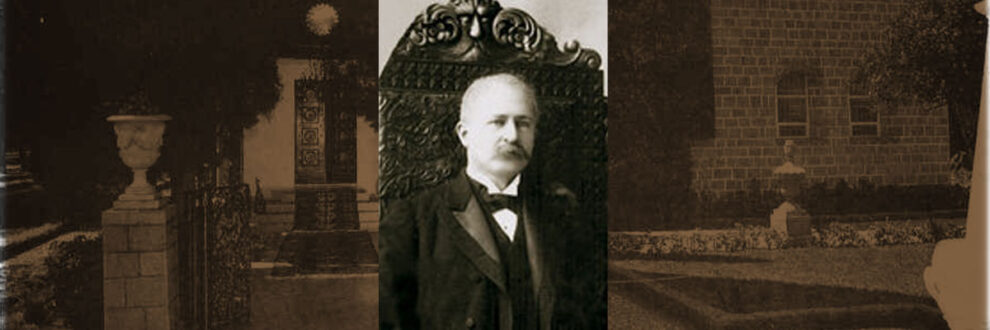

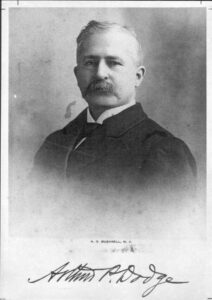

Arthur Pillsbury Dodge was born on May 28, 1849 in Enfield, New Hampshire, to Simon S. Dodge and Sarah A. C. Pillsbury. Simon, an artist, was a descendant of Richard Dodge, who arrived in Salem, Massachusetts, from England in 1629. Sarah, who was born in the nearby town of Canaan, was also descended from a long line of New Englanders. Simon and Sarah married in 1845; records indicate the couple had at least eight children, of whom Arthur was the third and the oldest son. The family lived in both Enfield and Canaan.

Arthur Dodge’s formal schooling was limited. According to his son Wendell, during the Civil War Dodge served as a drummer boy in the New Hampshire regiment of the Union Army that his father commanded. After the war, at the age of sixteen, Dodge began working as a reporter for the Manchester Daily Union (later the Manchester Union Leader), one of New Hampshire’s leading newspapers.

On November 2, 1870 Dodge married Elizabeth Ann Day (1854–1927) of Boston. They had six children: Arthur Galloup (1873–1883), Edgar Adams (1877–1877), William Copeland (1880–1973), Wendell Phillips (1883–1976), Anna Hall (1887–1895), and Richard Paul (1890–1953).

In 1879 Dodge began a new career as a lawyer, having studied law on his own, as was common at the time. He was admitted to the bar in New Hampshire in 1878 and in Massachusetts in 1880. During the 1880s and the early 1890s, he practiced law in Malden and Chelsea, Massachusetts. Later he was admitted to the bar in Illinois and New York.

In 1879 Dodge began a new career as a lawyer, having studied law on his own, as was common at the time. He was admitted to the bar in New Hampshire in 1878 and in Massachusetts in 1880. During the 1880s and the early 1890s, he practiced law in Malden and Chelsea, Massachusetts. Later he was admitted to the bar in Illinois and New York.

In 1880 Dodge expanded a brief sketch on the life of Phinehas Adams, a businessman from Manchester, New Hampshire, that he had written for the Manchester Daily Union, turning it into a flattering twenty-four-page biography. Several years later, while still practicing law, Dodge embarked on another career, that of publisher. In Boston in 1886 he helped revive and then managed a successful periodical, the New England Magazine, which published a mix of literary and historical essays. Edward Everett Hale, a renowned author, served as editor for a time.

Because of the success of the publication, Dodge became keenly interested in “educating the public unawares” and desired to found a national magazine. Finding Boston financiers unsupportive, he went to Chicago in 1891. George Pullman, the railroad magnate, whom Dodge approached about financing, gave Dodge an Augean task to accomplish first: to get an innovative but partially finished steam engine for a streetcar to work. Pullman had funded its development, but the designer had died suddenly, leaving a “white elephant.” Dodge plunged in, despite having neither an engineering background nor any awareness of possessing a mechanical bent, and thus embarked on an unexpected career as a mechanical engineer and inventor. Having outfitted the original streetcar with his new inventions, he arranged for it to operate on an experimental basis on Chicago’s West Madison Street cable car line. His design produced fewer cinders and sparks than its predecessors, was quieter, and recycled its water—improvements that other engineers were working on as well elsewhere.

Dodge’s relationship with Pullman was disrupted by the stock market crash and subsequent depression known as the Panic of 1893; the Pullman Strike of 1894, a major work stoppage that affected rail traffic throughout much of the country; and a subsequent decline in the magnate’s health, leading to his death in 1897. Having abandoned his dream of publishing a national magazine, Dodge pursued his inventions and established his own Kinetic Power Company. “To the chagrin, as well as dismay, of my mother,” Wendell Dodge recalled, Arthur Dodge turned down a multimillion-dollar offer for the company and all his patents made by Charles T. Yerkes, a financier who controlled most of the mass-transit lines in Chicago; instead, Dodge chose to maintain control of his inventions.

Dodge’s relationship with Pullman was disrupted by the stock market crash and subsequent depression known as the Panic of 1893; the Pullman Strike of 1894, a major work stoppage that affected rail traffic throughout much of the country; and a subsequent decline in the magnate’s health, leading to his death in 1897. Having abandoned his dream of publishing a national magazine, Dodge pursued his inventions and established his own Kinetic Power Company. “To the chagrin, as well as dismay, of my mother,” Wendell Dodge recalled, Arthur Dodge turned down a multimillion-dollar offer for the company and all his patents made by Charles T. Yerkes, a financier who controlled most of the mass-transit lines in Chicago; instead, Dodge chose to maintain control of his inventions.

Unable to find anyone in either Chicago or Boston willing to finance his business ventures beyond the experimental stage, he moved from Chicago to New York in 1897, obtained financing, and purchased a factory site in Delaware to produce his engines. Around this time Dodge also bought the Babylon Rail Road, a small streetcar line on Long Island, which he hoped to use to demonstrate his new streetcar design. For his various ventures, he sought support from Robert G. Ingersoll, a famous attorney and atheist author; Cornelius Vanderbilt II and William K. Vanderbilt of the prominent family of railroad owners; and the financier Russell Sage, among others.

During these years of economic success, Dodge obtained a farm in Bellevue, Delaware, to serve as a summer residence. His steam engines never sold, however, partly because urban railroads and subways were being electrified instead. In 1907 Dodge lost his fortune following a Wall Street crisis and had to sell most of his assets. Continuing to practice law, he managed to maintain the large family home at 261 West 139th Street in Manhattan (the 1910 census shows that the household included five lodgers).

Dodge had always been curious about religion and had attended many churches, but he became increasingly skeptical about Protestant teachings. According to his son, Arthur Dodge “successfully investigated and followed pretty nearly every cult and ism” before he encountered what he had been seeking:

Just before the loss of my sister Anna in the winter of 1895 my father had been told  something of the [Bahá’í] Cause by Dr. Sarah J. Burgess in Chicago. . . . He knew just enough . . . to be interested in it, and to have renewed hope that at last he had found the truth! In fact, if he had not felt keenly about it he might never have outlived the terrible shock to him of Anna’s death, for my mother said the only thing that seemed to keep him up at that time was what Dr. Burgess had told him of the Cause.

something of the [Bahá’í] Cause by Dr. Sarah J. Burgess in Chicago. . . . He knew just enough . . . to be interested in it, and to have renewed hope that at last he had found the truth! In fact, if he had not felt keenly about it he might never have outlived the terrible shock to him of Anna’s death, for my mother said the only thing that seemed to keep him up at that time was what Dr. Burgess had told him of the Cause.

Dodge’s business took him to the East Coast, however, before he could investigate further. Finally, in the fall of 1897, when he was about to move from Chicago to New York City, he met Dr. Burgess’s teacher, Ibrahim G. Kheiralla (1849–1929), a Lebanese immigrant who had become a Bahá’í in Egypt in 1890. Dodge received Kheiralla’s Bahá’í lessons in abbreviated form on October 27, 1897, and he invited Kheiralla to New York City to teach the religion there. In January or February 1898, Dodge and his wife, Elizabeth, took Kheiralla’s entire set of lessons in the first Bahá’í class held in New York City.

The Dodges immediately became active in the Bahá’í community. In a sense Dodge embarked on a fifth vocation: spreader of the Bahá’í Faith. In the spring of 1898 the New York Bahá’ís elected community officers—they did not yet know that local Bahá’í communities formed governing boards and chose Dodge to be their president. Arthur and Elizabeth Dodge and two of their sons, Wendell and William, went on pilgrimage to Acre in the fall of 1900. Returning to the United States via Britain, they visited Edward Granville Browne, the famous Cambridge orientalist who had met Bahá’u’lláh and ‘Abdu’l-Bahá in Acre; the Dodges asked Browne to translate letters (known as “tablets”) written by ‘Abdu’l-Bahá that they carried home with them. In New York, Dodge published the letters, with some of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s statements to him, as a booklet titled Tablets from Abdul Baha Abbas to Some American Believers in the Year 1900: The Truth Concerning A. “Re-incarnation”; B. “Vicarious Atonement”; C. “The Trinity”; D. Real Christianity. It was one of the first works of Bahá’í scripture published in the United States.

In 1901 Dodge published the first introductory book on the Bahá’í Faith written by a Western Bahá’í, The Truth of It: The Inseparable Oneness of Common Sense—Science—Religion. Chapters on common sense and science are followed by a series of chapters that define religion and criticize popular Christian understandings. The work culminates in a five-page chapter on the Báb, Bahá’u’lláh, and ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, followed by a chapter summarizing Dodge’s pilgrimage and by the texts of three tablets by ‘Abdu’l-Bahá. The book is as much an attack on corrupt clergy, secular-minded scientists, misdirected biblical scholars, foolish cultic beliefs, and organized religion as it is an explanation of a few Bahá’í teachings. It demonstrates how little a prominent American Bahá’í knew about the religion in 1900; the depth of Dodge’s alienation from the churches; and his frustration with scientists, who had displaced his inventions with ones deemed better. In 1903 he established the International Correspondence School of Prophecy and Bible Study to disseminate his lessons about the Bahá’í Faith’s fulfillment of biblical prophecy.

Dodge was elected to the New York Board of Counsel, the first Bahá’í governing body in that city, on December 7, 1900. By June 1901 he had apparently resigned from the body, possibly because of disagreements with other members. Two years later he received a tablet from ‘Abdu’l-Bahá alluding to personal conflicts. “Nobody has ever complained of you,” ‘Abdu’l-Bahá assured him, “and should anyone do so, it will not be listened to!” ‘Abdu’l-Bahá warned of the damage that disunity produces, urged Dodge to focus on unity, and stressed that the kindness to be shown to the whole human race must also extend to the Bahá’ís.

Dodge continued to be active in the New York Bahá’í community, though not always on its Board of Counsel. In 1906 the Board of Counsel listened to a dispute between Dodge and Howard MacNutt (1859–1926), another prominent early American Bahá’í, about the station of ‘’Abdu’l-Bahá. Neither man’s position was correct, as ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s station is understood today. Dodge maintained, in the words of Frank Osborne, a New York Bahá’í, that ‘Abdu’l-Bahá “was the return of the Christ in His Father’s Kingdom,” even though Dodge had received tablets in which ‘Abdu’l-Bahá had rejected such a claim. MacNutt viewed ‘Abdu’l-Bahá as an ordinary man who had attained His station, as another early Bahá’í put it, through “works and service.”

The New York Board of Counsel wrote ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, summarizing the two positions. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s reply emphatically denied that He was the return of Christ and emphasized His complete servitude to Bahá’u’lláh but did not touch on the question of whether ‘Abdu’l-Bahá had achieved His station through hard work and personal sacrifice. Consequently, in New York the reply was understood as a vindication of MacNutt’s point of view.

The tablet arrived just six weeks before the 1907 election of the New York Board of Counsel. MacNutt was elected to the body, but Dodge was not. Subsequently, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá wrote to a Bahá’í to insist that Dodge be treated with consideration and respect: “This personage is a believer and assured; he is attracted, enkindled and of the utmost sincerity. The believers of God must have the utmost consideration toward him; they must not avoid him; they must seek his companionship in a cheerful manner. . . . The point is this: the believers must associate with Mr Dodge with joy and love.” Dodge was again elected to the Board of Counsel in 1909, and he and his wife continued to host well-attended Bahá’í meetings in their home. In 1912 and 1913 he served as a delegate from New York to the annual convention of Baha’i Temple Unity, as the governing council for North America was known at the time.

Dodge published his third and last book, titled Whence? Why? Whither? Man, Things, Other Things, in 1907, the year in which a financial panic caused him to lose much of his fortune. The 269-page work begins with an exploration of the nature, purpose, and direction of human existence. The second part considers the nature of religion and offers interpretations of biblical passages and prophecies. The third section speaks of the coming of God’s Kingdom on earth. The final section discusses a miscellany of subjects such as racism, crime, church heresy trials, and strikes, expressing biting criticisms of such figures as Andrew Carnegie, the anti-religious scientist Andrew White, and the playwright George Bernard Shaw. The early American Bahá’í Thornton Chase commented that Dodge and some other Bahá’ís “are a trial to those who long to see the [Bahá’í] Cause appear in true wedding garments, and not in the shreds and patches of disordered imaginations.” He added, however, that Dodge is “all right” and that “the real inside of him is very sweet and good.”

‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s nearly eight-month-long visit to North America in 1912, during which He made New York City His base, provided Dodge innumerable opportunities to be in ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s presence. On April 16, less than a week after His arrival, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá addressed a large public meeting in the Dodges’ Manhattan home; His topic was “The Influence or Penetration of the Divine Power.” He also answered a number of questions on Bahá’í subjects and spoke to a gathering of children there. Another high point for Dodge occurred on November 12, when, at a gathering in the home of New York City Bahá’ís Edward and Carrie Kinney, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá “likened the faith of Mr [Arthur] Dodge to that of Peter and expressed His admiration for that sincere and true servant who was so firm in the Covenant.”

Early in 1914 Dodge and his family moved to Freeport, on Long Island, where they and other local Bahá’ís formed the “first Bahá’í Assembly [community] of Hempstead, in the County of Nassau and State of New York, and located in Freeport in said Township.” During the last two years of Dodge’s life, his son recounted, he lost much of the bitterness he felt toward the churches. “The Bahá’í Revelation had made of him a sweet-tempered soul and had given him an unlimited reserve and compassion.” Despite a painful terminal illness, Dodge “seemed not to mind his terrible suffering . . . and expressed himself as only regretting that he could not live long enough to complete his work for the Blessed Cause, to serve God and man as he never had been able to do!” He died at his home at 64 Jay Avenue in Freeport on October 12, 1915 and was buried in the Dodge family plot in Lakeside Cemetery, Wakefield, Massachusetts.

‘Abdu’l-Bahá eulogized Dodge in a tablet to the family:

In reality that honorable soul served the Cause of God and endured many hardships and vicissitudes. His services are registered in the everlasting book in the Kingdom of God and mentioned by the Supreme Concourse. They shall never be forgotten. Ere long they will yield great results and will become the means of happiness to that household and conducive to the honor of its members. I will never forget him and supplicate for him graces and bounties from his highness the Almighty. . . . Although his star set in the horizon of this world yet he dawned with the utmost brilliancy from the horizon of eternity.

Shoghi Effendi described Dodge as one of “the most prominent among those who, in those early years, awakened to the call of the New Day, and consecrated their lives to the service of the newly proclaimed Covenant.” He also numbered Dodge among “that immortal galaxy now gathered to the glory of Bahá’u’lláh—[who] will for ever remain associated with the rise and establishment of His Faith in the American continent, and will continue to shed on its annals a lustre that time can never dim.”

Shoghi Effendi described Dodge as one of “the most prominent among those who, in those early years, awakened to the call of the New Day, and consecrated their lives to the service of the newly proclaimed Covenant.” He also numbered Dodge among “that immortal galaxy now gathered to the glory of Bahá’u’lláh—[who] will for ever remain associated with the rise and establishment of His Faith in the American continent, and will continue to shed on its annals a lustre that time can never dim.”

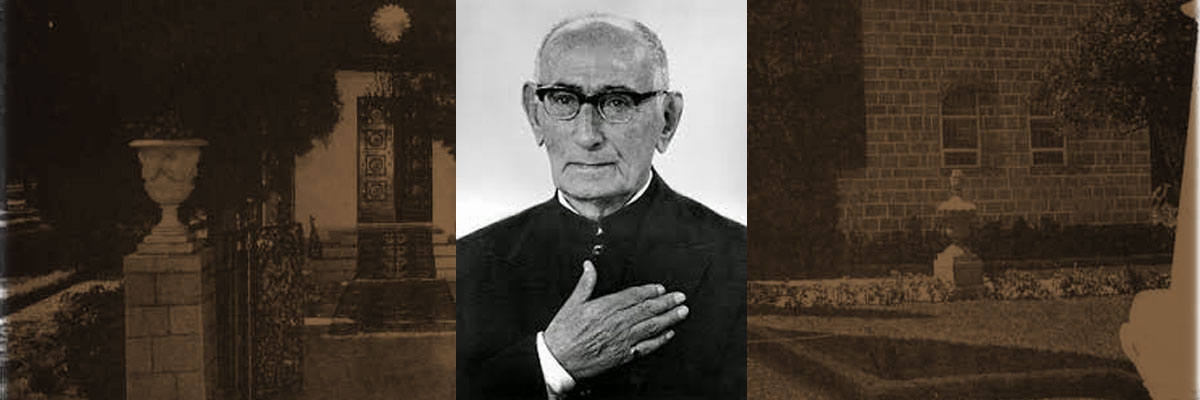

On Shoghi Effendi’s instructions, a list of photographs of “The Disciples of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá: ‘Heralds of the Covenant'” was published in the third and fourth volumes of the Bahá’í World in 1930 and 1933. On each list Dodge is number seventeen of the nineteen so designated, identified as “Mr. Arthur P. Dodge: staunch advocate of the Cause.”

Source:

Stockman, Robert H. “Thornton Chase” Bahá’í Encyclopedia Project, bahai-encyclopedia-project.org

Images:

Baha’i World Centre Archives

findagrave.com